From ancient times to the present day, great women have changed the course of history. Yet they are often overlooked by scholars, and rarely remembered by the public.

These 30 women in history changed laws, broke new scientific ground, and shattered gender barriers. Join us as we shine a light on their stories, and celebrate their contributions.

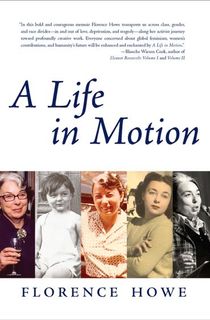

Florence Howe (1929-2020)

There are a few women from second-wave feminism whose names stand out, like Gloria Steinem and Betty Friedan. But have you heard of Florence Howe? Nicknamed "the Elizabeth Cady Stanton of women's studies," Howe began teaching the subject before it was a major or even had a name.

Born in Brooklyn in 1929, Howe was introduced to feminism when she participated in the civil rights and anti-war movements of the 1960s. During that time, Howe publicly refused to pay income taxes in protest of the Vietnam War and taught at a Freedom School in Mississippi as part of an effort to close the educational opportunity gap for black children.

Related: 10 Powerful Books to Read for Women's History Month

In 1970, Howe founded The Feminist Press, a publishing house dedicated to advancing women’s rights and amplifying the voices of unheard women. Howe began by publishing important female writers whose works had gone out of print, like Charlotte Perkins Gilman and Zora Neale Hurston and later introduced the world to new writers of diverse economic and racial backgrounds. Fifty years later, The Feminist Press is the longest surviving women’s publishing house in the world.

Learn more about Florence Howe.

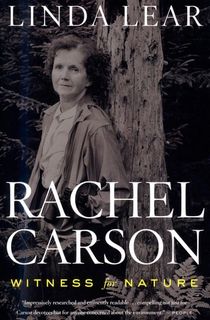

Rachel Carson (1907-1964)

When marine biologist Rachel Carson published Silent Spring in 1962, she changed the way we think about the environment. Throughout her life, Carson showed talent in both writing and the sciences; she was originally an English major at the Pennsylvania College for Women before switching to biology, and continued contributing to the student newspaper throughout her undergraduate education. Carson earned a master’s degree in zoology from Johns Hopkins University in 1932 and began working as an aquatic biologist in the U.S. Bureau of Fisheries. She earned a National Book Award for her 1951 book The Sea Around Us, but it was Silent Spring that launched her into a role as a literary celebrity and reformer.

Related: Rachel Carson's Books Defined an Environmental Revolution

Silent Spring exposed environmental issues to the U.S. public for the first time. Carson documented the adverse effects of synthetic pesticides for humans and wildlife, revealed that the chemical industry was spreading lies and misinformation, and accused U.S. officials of negligence in accepting the use of pesticides without fully examining the harmful effects. Carson’s book outraged the public and led to a nationwide ban on DDT, a cancer-causing insecticide. The Environmental Protection Agency also owes its existence to Carson’s influence, as her book caused citizens and the government to be more environmentally conscious. Carson was posthumously awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by Jimmy Carter. Today, she is remembered for being one of the first people to alert others about the dangers of our environmental impact and inspiring the movement for sustainability.

Learn more about Rachel Carson.

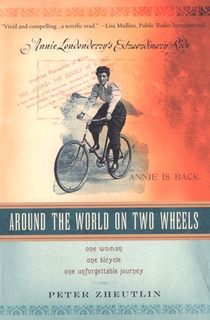

Annie Londonderry (1870-1947)

"I am a journalist and a 'new woman,' if that term means that I believe I can do anything that any man can do." So begins the article that Annie Londonderry wrote when she returned to the United States after becoming the first woman to cycle around the world.

Londonderry was born Annie Cohen Kopchovsky in Latvia, and immigrated to the United States as a young child. At 24 years old, Londonderry used her pseudonym to reinvent herself as a globetrotting cyclist and saleswoman. Rumor had it that two wealthy Boston men had wagered tens of thousands of dollars that no woman could cycle around the world in just 15 months, and Londonderry challenged them. However, historians now believe that Londonderry concocted this story in order to fuel excitement in her journey and encourage companies to sponsor her trip by paying for advertising space on her bicycle.

In 1894, Londonderry set off on her journey with just a bicycle, a pearl-handled pistol, and a change of clothes–including bloomers, the controversial garment that increased women’s mobility. Despite suffering injuries and setbacks along the way, she successfully completed her trip with 14 days to spare. Sailing from country to country when necessary, Londonderry was able to travel the world and visit faraway cities including Alexandria, Saigon, Hong Kong, and Kobe. This was no small feat for a wife and mother at the time. Londonderry’s travels proved to her contemporaries that women can be independent, athletic, and entrepreneurial.

Learn more about Annie Londonderry.

Dolores Huerta (1930-Present)

There’s a whole day dedicated to César Chávez at the end of March—but what about the woman who worked with him to co-found the National Farmworkers Association?

Dolores Huerta was born into a family of Mexican immigrants in 1930. Her father worked harvesting beets, and after her parents’ divorce, her mother owned a restaurant which welcomed farm and low-wage workers at affordable prices. It’s no surprise that Dolores was inspired to pursue a life as a civil rights activist.

Though her activism began in high school, it was at the age of 25 that Huerta's efforts really took off. To fight for economic improvements for Latino/Mexican/Chicano migrant farm workers, Huerta co-founded the Stockton Chapter of the Community Service Organization (CSO). Five years after that, she co-founded the Agricultural Workers Association to push for barrio improvements. It was two years later that she and Chavez founded the National Farmworkers Association, which would later be called the United Farm Workers Organizing Committee. She sat on the board of the UFW—the only woman to do so until 2018.

Along with her founding efforts, she’s also known for lobbying for several important bills to improve the lives of farm workers, including a 1960 bill to permit Spanish-speaking people to take the California driver's examination in Spanish, a 1962 legislation repealing the Bracero Program, a 1963 legislation to extend the federal program, Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC), to California farmworkers, and the 1975 California Agricultural Labor Relations Act.

Ellen Ochoa (1958-Present)

Born in Los Angeles, California, Ochoa’s maternal grandparents had immigrated from Sonora, Mexico. After getting her bachelor of science degree in physics from San Diego State University in 1980, Ochoa went on to the Stanford Department of Electrical Engineering for her masters and doctoral studies.

Her early career was spent as a researcher at Sandia National Laboratories and the NASA Ames Research Center, where she investigated optical systems for performing information processing. She even patented an optical system to detect defects in a repeating pattern. At Ames she was the Chief of the Intelligent Systems Technology Branch, supervising 35 engineers and scientists in the research and development of computational systems for aerospace missions.

Related: 8 Books About the History of Space Exploration

Perhaps most impressively, she was the first Hispanic woman to go up into space in 1993. Aboard the Space Shuttle Discovery, Ochoa served on a nine-day mission where she studied the Earth’s ozone layer. But this certainly wasn’t her final space mission. Logging nearly 1,000 hours in space, her mission aboard Discovery was merely one of four. In 2007, Ochoa became Deputy Director of the Johnson Space Center, before becoming the first Hispanic and second female director of NASA's Johnson Space Center in 2013.

Patsy Mink (1927-2002)

A third-generation Japanese American, Patsy Mink was raised on the Hawaiian island of Maui. The valedictorian of her high school, Mink eventually went to study at the University of Nebraska before an illness forced her to continue her education back home. She applied to dozens of medical schools—all which rejected her. But that wouldn’t keep her from greatness. She decided to pursue law instead, and in 1948 she attended the University of Chicago Law School.

Unfortunately, in 1951 her status as a married Asian woman left her unable to find work. She was even refused the right to take the bar exam in Hawaii, as she lost her territorial residency upon marriage. She challenged this sexist statute, and though she was able to take and pass the bar, she found work only after starting her own practice in 1953. She was determined to find a way to end discriminatory customs, and ran for a seat in the U.S. House of Representatives in 1964.

Related: 30 Biographies of Remarkable Women That You Need to Read

Mink was not only the first Japanese American to be elected to Congress, but the first woman of color in general to win the seat. She served for a total of twelve years, having involvement in such issues as the first federal child-care bill, the Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965, and a lawsuit which led to significant changes to presidential authority under the Freedom of Information Act in 1971. She was also the co-author of the Title IX Amendment of the Higher Education Act, which prohibits sex-based discrimination in schools.

Jillian Mercado (1987-Present)

Though she’s only in her 30s, Jillian Mercado has made incredible strides in the modeling and activism community. A New York native with Dominican ancestry, Mercado was diagnosed with spastic muscular dystrophy as a child. Besides visible muscle weakness throughout her body, Mercado is also in a wheelchair—a situation which has been rarely represented within society’s beauty standards.

But Mercado has always had a love for the fashion industry, despite its Eurocentric beauty standards and ableist stigma. She vowed to change these attitudes from the inside out. She went to college at FIT, where she earned her degree in marketing. Following this, she even interned at Allure magazine. In reference to these choices, Mercado has said she wanted to “learn the politics behind fashion so I could hire people who looked like me.”

While Mercado studied at FIT, she served as a model for some of her fellow students’ projects. But in 2014 she saw her first professional modeling gig in a campaign for denim brand Diesel. Not long after, she was signed by IMG Models, appearing in widespread campaigns for the likes of Nordstrom, Target and Olay. Besides appearing on a New York City billboard, Mercado was also featured as a model for merchandise for Beyoncé’s Formation world tour. She was the first disabled cover star of Teen Vogue, and continues to use her impressive platform to push for more inclusivity in the industry.

Fatima al-Fihri (c.800 AD-c.880 AD)

Born in Kairouan in Tunisia, Fatima al-Fihri was the daughter of a wealthy Muslim merchant. Though there’s a lot of mystery surrounding this woman’s history, one thing is for certain—she established the al-Qarawiyyin mosque in 859 AD in Fez, Morocco. This mosque later became the famous al-Qarawiyyin university, which is now recognized as the oldest surviving university in the world.

When she first decided to build the mosque, she was in a good position to do so, having inherited money from both her father’s and husband’s deaths. The Muslim community in Fez was rapidly expanding, and as the numbers of believers grew, al-Fihri felt they needed a place to go. The mosque became the first religious institution in North Africa, and as it became a university, the largest Arab university of North Africa.

Related: 25 World History Books That Will Give You a New Perspective

Students and scientists flocked to the institution. The university boasts such graduates as historian Abdurahman Ibn Khaldun, the doctor and philosopher Abu Walid Ibn Rushd, the Andalusian doctor Musa Ibn Maimonou, as well as Gerbert of Aurillac, who became Pope Sylvester II. Besides providing education to hundreds of thousands of students across centuries, this institution was crucial in the exchange of Muslim and European ideas during medieval times.

Wangari Maathai (1940-2011)

Wangari Maathai was born in Nyeri, Kenya in 1940. She attended Mount St. Scholastica College where she earned her degree in Biological Sciences, before moving on to get her Master of Science degree from the University of Pittsburgh, and eventually obtain her Ph.D. in veterinary anatomy from the University of Nairobi. She was the first woman in East and Central Africa to ever earn a doctorate degree.

Her most incredible contribution to history was her establishment of the Green Belt Movement in 1977. She founded this environmental organization in response to the reports from rural Kenyan woman who said that they were encountering difficulties feeding themselves and their families in light of dried up streams and other environmental changes.

Maathai encouraged communities—and women in particular—to work in tandem with each other to bind soil by planting seedlings and trees, store rainwater, provide a supply of both food and wood, and get a small bit of monetary compensation for their efforts. This mission contributed to environmental conservation, as well as community management and economic cultivation.

From 2002 to 2007, Maathai served in Kenya’s parliament, and in 2004, she won the Nobel Peace Prize for her efforts toward sustainability and her devotion to democracy. In her lifetime, this incredible woman penned four books: The Green Belt Movement, Unbowed: A Memoir, The Challenge for Africa, and Replenishing the Earth. She and the Green Belt Movement are also at the center of the illuminating award-winning documentary Taking Root.

Gertrude Elion (1918-1999)

Gertrude Elion was a brilliant woman of Jewish descent who won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine alongside George H. Hitchings and Sir James Black. The prize was awarded to them for their use of rational drug design over trial-and-error methods.

Elion played a significant role in the production of the drug azidothymidine (AZT), which was one of the first drugs used to treat HIV and AIDS. Other important contributions she made were to the creation of the leukemia treatment drug, Purinethol; the immunosuppressive agent used for organ transplants, Imuran; the malaria drug, Daraprim; and the viral herpes treatment, Zovirax. She was also a key mind working on the cancer treatment Nelarabine until her death on February 21, 1999.

Related: 13 Female Scientists Who Shaped our Understanding of the World

She was inspired to get into biochemistry and pharmacology when she was 15 years old, after losing her beloved grandfather to cancer. Her tireless work from that moment on earned her prominent awards other than the Nobel Prize, including the Garvan-Olin Medal, the National Medal of Science, and the Lemelson-MIT Prize. Overcoming the great gender biases of the time, Elion’s work saved and enriched countless lives, and her passion for science encouraged many other women to follow in her footsteps.

Sarojini Naidu (1879-1949)

Known as “Bharatiya Kokila”—the Nightingale of India—Sarojini Naidu was a poet, activist and politician. She fought for civil rights, women’s emancipation, and anti-imperialism, and stood at the forefront of India’s battle for independence from British rule. In 1925, Naidu became the first Indian woman to be appointed President of the Indian National Congress, one of the country's major political parties.

Naidu was a follower of Mahatma Gandhi, and a strong proponent for his idea of swaraj—Indian freedom from foreign domination. She traveled to deliver lectures on social welfare, women’s empowerment, and nationalism. The British government awarded Naidu the Kaisar-i-Hind Medal for her selfless work during India’s plague epidemic, but she returned it in protest in response to the 1919 Jallianwala Bagh massacre.

Her first published work was the poetry collection The Golden Threshold, released in 1905. Her most famous poem is “In the Bazaars of Hyderabad”. "In the Bazaars..." is still taught in Indian secondary schools and European universities to this day.

Mary Anning (1799-1847)

Born in Lyme Regis, England, Mary Anning is known to some as one of the greatest fossilists to date. Many social factors of the era worked against her. Anning came from an impoverished family; she lacked a formal education; and the fact that she was a woman kept her out of scientific discussions, even when she contributed the fossil evidence. However, none of this kept her from shaping the growing paleontological science and shedding light on some of evolution’s big mysteries.

Alongside her brother, Anning discovered one of the first significant ichthyosaur fossils, which provided the data for the very first scientific paper on the specimen. She’s also credited with finding one of the first complete plesiosaur fossils, discovering the fossil fish which drew an evolutionary bridge between sharks and rays, and uncovering fossilized feces that provided key information to deduce the diets of ancient animals. Many more important Jurassic marine discoveries are thanks to her incredible efforts, and such finds laid crucial groundwork in the burgeoning discussions on extinction and evolution.

While Anning’s legacy has withered in obscurity for far too long, as of late she’s getting some of the attention she’s always deserved. London’s Natural History Museum opened up a new set of rooms—including a study full of biological treasures—which are named after Anning. A fund has been created to raise money to erect a statue in Lyme Regis to celebrate her accomplishments. You can also see Anning on the big screen: Kate Winslet took a turn as Anning in the 2020 film, Ammonite.

Sappho (c. 630-c. 570 BC)

This Archaic Greek poet hailed from the island of Lesbos. Often referred to as the “Tenth Muse” by her ancient compatriots, her poetry had a beautiful lyrical quality, which lent itself to be accompanied by the lyre. Unfortunately, most of Sappho’s works have been lost to time, and those remaining poems are mere fragments of her writings. The one exception to this is the “Ode to Aphrodite”, a full length poem about the goddess of love.

One of the greatest controversies surrounding the profound and romantic poetess is the issue of her sexuality. Many scholars throughout history have had heated debates about her proclivities, but that hasn’t been able to change her status as a symbol for women loving women. The term “sapphic” is derived from her name, while the more common term “lesbian” is a derivative of her birthplace.

While the context of the times complicates interpretations and the cycle of translations leaves doubt to original intentions, the modern implications of what little we have to read from Sappho certainly evokes a feminine and homosexual eroticism.

Regardless of the murky waters of her ancient personal life, she was a highly respected and celebrated writer. Sappho's likeness was even emblazoned onto coinage and carved into statues. Today, she is studied by scholars, regardless of the limited information about her work and life. But though her legacy may remain only in pieces, she shaped the culture of her time which grew into the society we see today.

Victoria Cruz (1945-present)

For those familiar with the Stonewall Riots, the names of Marsha P. Johnson and Sylvia Rivera may ring a bell. Less known is their contemporary, Victoria Cruz. Born in Guánica, Puerto Rico, Cruz moved with her family to Brooklyn at a very young age. As a young adult, Cruz—who says she never hid any aspect of who she was—took control of her identity and obtained hormones and gender reassignment surgery.

A trans woman of color, Cruz is one of few who lived through the oppressive period of the Stonewall protests and survived to tell the tale. Cruz attributes her safety to her small stature—she was able to "pass" in a way many of her trans compatriots were not.

Related: 11 Fascinating LGBT History Books to Read for Pride Month

Cruz was present the night the police flooded the Stonewall Inn in a raid. That night was not the end of her troubles. After suffering abuse from police, fellow sex workers, and coworkers at the nursing home where she worked, Cruz began employment at the Anti-Violence Project. In the two decades she worked there, Cruz became a senior counselor advocate, and went on to receive the Justice Department’s National Crime Victim Service Award from the Obama administration in 2012.

Providing her voice to the vital Netflix documentary The Death and Life of Marsha P. Johnson, Cruz has garnered some more notoriety and attention. Participating in talks like Brooklyn College’s “Trans Activism Before, During, and After Stonewall” discussion, Cruz has used this new attention to continue to educate others and garner awareness on transgender issues.

Madonna Thunder Hawk (1940-present)

A member of the Oohenumpa band of the Cheyenne River Sioux River Tribe, Madonna Thunder Hawk is a prominent Indigenous activist. She was one of the first followers of the Red Power movement, and participated in the 1969-71 Occupation of Alcatraz, which aimed to convince the federal government to adopt a policy of Indian self-determination. She also became a part of the American Indian Movement (AIM) within its beginning years.

In 1974, Thunder Hawk founded Women of All Red Nations (WARN) alongside several other indigenous women. This organization was in response to the often male-dominated politics of AIM and the Red Power movement, choosing to focus on sterilization abuse, political prisoners, children and family rights, and threats to indigenous land bases.

She also helped to form the Lakota People’s Law Project (LPLP) with the hope of pushing a more consistent enforcement of the Indian Child Welfare Act. As the movement against the Dakota Access pipeline rose in 2016, Thunder Hawk became a profound and inspiring voice amidst the protests.

Thunder Hawk is also a founder of the Warrior Women Project, which seeks to help “indigenous activists to tell their stories in their own words for the benefit of future generations.” The documentary generated by the project—similarly titled Warrior Women—centers around Thunder Hawk and her life from the 1970s through to her current activism.

Peggy Shippen Arnold (1760-1804)

We’ve all heard about the traitorous Benedict Arnold, who betrayed America in its struggle for independence from Great Britain. However, we hear little about his wife, Peggy Shippen Arnold, who actually played a pivotal role in the treachery.

Benedict Arnold clued Britain into confidential American military strategy, sabotaging American colonists’ plans. For a long time, Peggy was considered to be innocent of any treachery, but historians now believe that she may have actually masterminded the deceit.

Growing up, Peggy’s family decided to support the British, for both security and financial reasons. After Peggy and Benedict wed and the two moved to Philadelphia, the couple began secretly corresponding with the British through a contact of Peggy’s. Peggy was part of a women’s circle in which she would pass letters on to British Major John Andre, written in code and invisible ink, filled with private information about American military locations and plans.

Alice Coachman (1922-2014)

At the 1948 London Olympics, Alice Coachman won the high jump for the United States, becoming the first black woman to win an Olympic Gold medal. King George VI awarded her medal, and subsequently, President Harry S. Truman congratulated her at a White House ceremony. Coachman was also celebrated in a motorcade that traveled from Atlanta to her hometown of Albany, Georgia.

As a child, Coachman was forbidden from training at athletic fields with white people, which forced her to get creative: she would use ropes and sticks as high jumps, running barefoot. Despite these barriers, she was able to be the first black woman to win an Olympic medal and the first black person to receive an endorsement deal.

Related: Game On: 10 Best Sports Books Ever Written

“If I had gone to the Games and failed, there wouldn’t be anyone to follow in my footsteps. It encouraged the rest of the women to work harder and fight harder,” Coachman told The New York Times in 1996. And indeed, she paved the way for African American athletes like Wilma Rudolph, Evelyn Ashford, Florence Griffith Joyner, and many more.

Margaret Hamilton (1936-present)

Mankind successfully set foot on the moon in 1969. While history's spotlight remains trained on the pivotal men of NASA, there were several women who played an essential role in the Apollo 11 mission. Margaret Hamilton is one of those important women.

As the leader of the Software Engineering Division of the MIT Instrumentation Laboratory, contracted by NASA for the Apollo program, Hamilton helmed the development of the spacecraft’s guidance and navigation system. Her team developed the framework for software engineering, and she worked tirelessly in testing Apollo’s software.

Thanks to Hamilton’s rigorous testing of the software, Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin successfully landed on the moon, despite a software override. In 2003, NASA honored Hamilton with a special award recognizing the value of her software innovations. In 2016, President Obama awarded Hamilton a Presidential Medal of Freedom, the highest civilian award in the United States.

Hamilton was, of course, preceded by women like Katherine Johnson and the other great women of Hidden Figures. Women’s contributions have been vital to NASA since its inception.

Wu Zetian (624-705)

Wu Zetian was the only female emperor in Chinese history. She used every ounce of her political skills and pulled Machiavellian maneuvers to gain and maintain her power.

In dynastic China, Confucius deemed women unfit to rule. Nevertheless, Wu Zetian rose through the ranks in Chinese society. Wu’s intellect and beauty attracted Emperor Tai Tsung, who recruited her to his court as his concubine. After the emperor’s death, his son Kao Tsung succeeded him.

Kao Tsung had been having an affair with Wu even before the death of his father. She became his second wife—a large step up from concubine—after his ascension. She gave birth to a daughter soon after they married, who died young. Wu blamed the first wife, Empress Wang, although some people believe that Wu herself killed her daughter.

Emperor Kao Tsung later died from a stroke, and Empress Wu began administrative duties in the court, eliminating and spying on those who posed an obstacle to her, and putting her youngest son into power. When her son stepped down in 690, Wu was crowned emperor of China. As emperor, Wu truly did effect change in China. She gave government positions to qualified scholars, reduced the army’s size, lowered unfair taxes on peasants, and increased agricultural production.

Sybil Ludington (1761-1839)

Statue of Ludington in Carmel, NY

Photo Credit: Wikimedia CommonsWhile there seems to be a chorus of praise for American revolutionary Paul Revere, we haven’t heard much of the female revolutionary who rode even farther through the night in the name of American freedom.

On April 5, 1761, Sybil Ludington was born to Abigail and Colonel Henry Ludington, a veteran of the French and Indian War. When Sybil’s father found out that British troops were attacking Danbury, Connecticut, 25 miles from the family’s New York State home, 16-year-old Sybil took it upon herself to warn the countryside of the coming British invasion. By horse and in the pouring rain, she travelled 40 miles to announce that the British were coming. Her ride proved successful, because when she arrived back from her trip, hundreds of troops were assembled in front of her home.

Related: 9 Fascinating Books About the Founding Fathers of America

After her successful ride, Ludington continued to serve as a messenger in the Revolutionary War. Although President George Washington thanked her for her service, she faded into obscurity soon thereafter. It's worth noting that not every historian is convinced of the story of Sybil Ludington. Paula D. Hunt published a paper in The New England Quarterly in which she scrutinizes the account, attempting to separate fact from fiction. However, other organizations and outlets—from the National Women's History Museum to the New England Historical Society and American historian Carol Berkin in her book Revolutionary Mothers—stand by the midnight ride.

Huda Sha'arawi (1879-1947)

Raised in an Egyptian harem system, Huda Sha’arawi had the desire to advocate for women at an early age. At the time in Egypt, upper-class families dedicated separate buildings to housing and protecting women; the buildings were guarded by eunuchs, who also acted as the women’s messengers. Women of all religions stayed in these “harems,” separate from men, and wore veils in public.

Huda’s upbringing led her to challenge the notion that women need protecting. In 1908, she founded Egypt’s first female-run philanthropic society, which offered services for impoverished women and children. As more education opportunities became available for Egyptian women, Huda planned lectures to educate women, and eventually organized the largest women’s anti-British protest. Once Egypt gained independence from Britain in 1922, it was expected that women would go back to life in the harem–but not under Huda Sha’arawi’s watch.

She then decided to make a decision that would prove revolutionary for Egyptian women: After stepping off of a train in Cairo, Huda removed her veil in public. After Huda’s rebellious act, few Egyptian women continued to wear the veil. She continues to have a lasting influence on women not only in the Middle East but also around the world.

Related: Night Witches: The Fierce, All-Female Soviet Fighter Pilots of WWII

Henrietta Lacks (1920-1951)

Lab-grown human cells are invaluable to medical researchers. They allow scientists to better understand complex cells and theorize about diseases. The first “immortal” cell of its kind was created in 1951 at Johns Hopkins Hospital, its donor remaining unknown for years. But we now know that those cells belonged to Henrietta Lacks.

From southern Virginia, Henrietta was a Black tobacco farmer who was diagnosed with cervical cancer at 30. Without her knowing, her tumor was sampled and sent to scientists at Johns Hopkins. Much to the scientists’ surprise, her cells never died. Henrietta’s immortal cells were integral in developing the polio vaccine, and were used for cloning, gene mapping, and in vitro fertilization.

For decades, the donor of these cells, which were code-named HeLa, remained anonymous. In the 1970s, Henrietta’s name was revealed and the origins of HeLa, a code for the first two letters in Henrietta and Lacks, became clear. While Henrietta Lacks may no longer be with us, her contribution to science is long lasting. A book about her invaluable and forced contributions was also made into a film starring Oprah and Rose Byrne.

Trưng Trắc and Trưng Nhị (c. 12-c. 43 AD)

It can be said that the existence of Vietnam today is due almost wholly to the efforts of the Trưng sisters. Prior to 40 A.D., the Chinese conquered Vietnam, leaving the country under the brutal rule of Chinese governor To Dinh. The daughters of a powerful Vietnamese lord, Trưng Trắc and Trưng Nhị were determined to change the state of affairs Vietnam.

Elder sister Trắc decided to mobilize Vietnamese lords to rebel against the Chinese rule. It is said that, to further their cause, the Trưng sisters killed a people-eating tiger and used its skin to write a declaration against the Chinese.

Among the 80,000 people they rallied for their uprising, the Trưngs chose 36 women to be generals, who successfully drove the Chinese out in 40 A.D. Trắc became queen, abolishing tribute taxes and struggling to revert back to a simpler government. After their troops suffered terrible defeat in 43 A.D., legend has it that the sisters took what the Vietnamese considered to be the honorable way out: suicide.

The Trưngs’ bravery and sacrifices made for Vietnam continue to be honored today through stories, poems, posters, monuments, and more. Although the sisters are well-known in Vietnam, their contributions are unnoticed elsewhere, especially within Western countries.

Dorothy Lawrence (1896-1964)

Left: Dorothy Lawrence in her teens. Right: Dorothy Lawrence as a solder

Photo Credit: Wikimedia CommonsDorothy Lawrence was a reporter in England who disguised herself as a man to fight in WWI, thus making her the first confirmed female to fight in the English army. In 1915, with her chest flattened by a corset, her hair completely cut off, and her complexion darkened, Lawrence decided to leave her job as a journalist and head to the front lines.

Lawrence didn’t spare any of the details of her disguise: She borrowed a khaki military uniform from two British soldiers, asked the soldiers to teach her how to walk more androgynously, and forged travel permits for war-torn France. After serving in the military for a brief 10 days, Lawrence fell ill, and because of worsening symptoms, decided to reveal her identity to her commanding sergeant. She was put under military arrest.

Related: 7 Famous Female Warriors Who Took the Battlefield By Storm

Upon her return to England, she was interrogated as a spy and deemed a prisoner of war; she also swore an oath not to write about her experience as a soldier in disguise. In 1919, against England’s wishes, Lawrence published Sapper Dorothy Lawrence: The Only English Woman Soldier, which was a commercial flop despite critical interest and left her with no income.

In a state of despair, Lawrence told a doctor that her church guardian raped her as a child. She was declared insane and committed to an asylum, where she remained until her death in 1964.

Edmonia Lewis (1843-1907)

Little is known about the early life of mid-19th century sculptor Edmonia Lewis, but she was reportedly born on July 14, 1843—although that is up for debate as well. Lewis is considered the first woman sculptor of African American and Native American heritage.

She began her education in 1859 at Oberlin College in Ohio, where she was said to have been quite artistic, particularly in drawing. During her undergraduate years, she changed her name to Mary Edmonia, which she had been using anyway to sign her sculptures. While at Oberlin, Lewis was wrongly accused of theft and attempted murder. Though she was eventually acquitted, she was prohibited from graduating.

When she moved to Boston, she was mentored by sculptor Edward Brackett and began to develop her own artistic style. Her dual ancestry proved to be a source of much inspiration for her, as her early sculptures were medallions with portraits of white abolitionists and Civil War heroes.

“Forever Free” (1867), one of her best-known works, drew from the Emancipation Proclamation. In 1876, Lewis completed what is considered by many to be the pinnacle of her career: “The Death of Cleopatra”. This sculpture went against artistic traditions of the time by portraying a realistic illustration of the event, instead of using a sentimental manner.

Hypatia of Alexandria (370-415)

A depiction of the death of Hypatia.

Photo Credit: Wikimedia CommonsWe hear about the lives and contributions of classical Greek luminaries and philosophers like Aristotle, Plato, and Socrates, but what about the important women who lived at the same time? Hypatia of Alexandria is one of these influential female scholars.

Growing up, Hypatia’s scholar father Theon taught her mathematics, astronomy, and philosophy in hopes of giving her the same opportunities available to men. Soon enough, Hypatia had students of her own to whom she taught mathematics and philosophy. She was an acclaimed teacher, with many of her students returning for years to discuss arcane and intricate matters.

Related: These Outstanding Greek Mythology Books Open the Doors to the Past

At the time, Alexandria was transforming into a Christian city; the pagan Hypatia was viewed by Christians as an obstacle to her students' proper religiosity. Extremely dedicated to her studies, Hypatia never married and remained celibate through her life.

In March of 415 CE, Hypatia was on her way home when she was attacked by a mob of Christian monks, stripped naked, dragged through the city, and beaten to death. After her death, many scholars and artists left Alexandria, viewing Hypatia’s murder and the Christianization of Alexandria as the death of intellectualism and the arts.

Grace Hopper (1906-1992)

Grace Hopper was the first woman to earn a Ph.D. in mathematics from Yale University in 1934, but she accomplished much more. After receiving her master’s degree, she taught as an associate professor at Vassar until she enlisted in the Navy during World War II.

An experienced mathematician, Hopper was assigned to the Bureau of Ordnance Computation and contracted to program a Mark I computer. As a researcher at Harvard, she then worked on the Mark II and III computers, helping popularize the term “computer bug.” After her tenure with the Navy, Hopper worked for the Eckert-Mauchly Computer Corporation, and then as a programmer for Remington Rand. Hopper and her team are responsible for creating the first compiler for computer languages, a precursor for the Common Business Oriented Language (COBOL), which is now widely used.

Hopper changed the face of programming. Her legacy continues to inspire young people, through efforts like the Grace Hopper Celebration of Women in Computing Conference, which encourages women to become programmers, and the Grace Murray Hopper Award through the Association for Computing Machinery.

Zelda Fitzgerald (1900-1948)

Zelda with her husband F. Scott Fitzgerald.

Photo Credit: Wikimedia CommonsBehind many male authors are accomplished wives and women who are often overlooked by history. Zelda Fitzgerald is one of these women.

“The most enormous influence on me in the four and a half years since I met her,” The Great Gatsby author F. Scott Fitzgerald told Edmund Wilson, “has been the complete, fine and full-hearted selfishness and chill-mindedness of Zelda.” While Zelda Fitzgerald is often regarded as a mere spectator to her husband’s literary success, she was the inspiration for nearly all of F. Scott’s heroines. And the literature she wrote on her own is just as accomplished as her husband’s.

Zelda’s remarks and writings were repackaged into F. Scott Fitzgerald’s books, and she knew it, too. In a review of her husband’s novel The Beautiful and the Damned (1922), she wrote, “plagiarism begins at home.” F. Scott would look through his wife’s letters and diaries for inspiration, tidbits of which Zelda recognized in his books. In fact, one of the most well-known lines from Gatsby is what Zelda said to him, word for word, when she learned the sex of her child: “I hope it's beautiful and a fool—a beautiful little fool.”

Rose Marie McCoy (1922-2015)

Much like many of today’s Top 40 radio hits, the chart-topping songs of the 1940s and 50s weren’t written by the performers, but by lesser-known songwriters who operated behind the curtain. One of these old-time songwriters is Rose Marie McCoy.

At 19, McCoy moved from Arkansas to New York City to pursue her dream of being a singer. She was a indeed a gifted vocalist, but in the late ‘40s she decided to pursue her true calling, songwriting. Her song “Tryin’ to Get to You” was performed by Elvis Presley on his debut album and soared to the top of the charts.

As an African American woman living in the 1960s, McCoy accomplished a remarkable feat when she got a private office in the Brill Building, the songwriting hub of the time. Her lyrics continued to resonate with everybody and she went on to write for the likes of James Brown, Nat King Cole, and Johnny Mathis. McCoy’s “I Think It’s Gonna Work Out Fine,” sung by Ike and Tina Turner, earned a Grammy nomination. McCoy went on to write for Linda Ronstadt and James Taylor and composed several commercial jingles performed by Aretha Franklin and Ray Charles.

She was approached by prominent record companies who wanted to sign her, but refused all of their offers. In total, she wrote approximately 850 songs, a shocking number for someone so few have heard of. At least McCoy is finally getting the attention she deserves: A 2009 NPR radio documentary featured her work, including some of her most famous songs.

Shirley Chisolm (1924-2005)

“Before Hillary Clinton, there was Shirley Chisholm,” the title of a BBC article reads. As the first black woman to run for president with a major political party, Shirley Chisholm is undoubtedly groundbreaking. Why isn't Chisholm in our history textbooks?

In January of 1972, Chisholm announced her presidential candidacy. While her campaign had a short run, it remains significant. And her presidential campaign wasn’t Chisholm’s only first—she was also the first African American congresswoman.

Related: How a Movement Grows: 100 Years of the 19th Amendment

Chisholm was born in Brooklyn, New York, in 1924. While working in childcare, she became interested in politics, serving in the New York state assembly and then becoming the first African American congresswoman in 1968. Needless to say, during her tenure in Congress, Chisholm shattered many a glass ceiling: she fought for the underprivileged and minorities, pushing forward a bill for domestic worker benefits, advocating for improved access to education, and fighting for immigrant rights.

She then decided to break the biggest of boundaries by running for president. "I ran because most people thought the country was not ready for a black candidate, not ready for a woman candidate. Someday, it was time in 1972 to make that someday come," she told an interviewer at the time. Her slogan, “Unbought and unbossed”, remains legendary to this day.

Featured photo of Peggy Arnold, Edmonia Lewis, and Zelda Fitzgerald: Wikimedia Commons