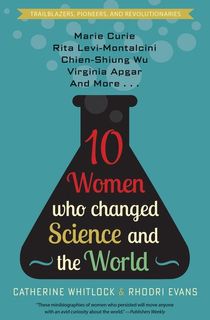

Female scientists have changed the world for centuries—often against all odds. They may not have gotten due credit in their time, but these female scientists broke through the barriers and paved the way to the future. The accomplishments of just a few of these incredible women are fully elaborated in Catherine Whitlock and Rhodri Evans’ biography, 10 Women Who Changed Science and the World, which further details the careers in which each profiled woman excelled.

The achievements of some of the women on this list have earned them Nobel Prizes for their discoveries—and it sure wasn’t easy in a male-dominated field. Despite the hardships, these women persevered and made a name for themselves in their respective fields. Take a look at these 13 of the many women who have, and continue, to shape the world of science and history. Can't get enough? Be sure to check out 10 Women Who Changed Science and the World for even more exciting stories about other scientists who just happened to be women.

Marie Curie

When you think of a female genius, the first name that comes to mind is probably Marie Curie. Born in Warsaw in 1867 as Maria Skldowska, she began her scientific training early, at her father’s side. After becoming a governess to support herself and her sister, Skldowsa was able to save enough money to travel to France to attend the University of Paris at the Sorbonne, where she studied chemistry, mathematics, and physics.

In 1895, Skldowsa married Jacques Curie, whom she had met in the lab, wearing the suit that would serve her as a lab coat in the years to come. The very next year, a new discovery invigorated Curie’s scientific career. Other researchers had discovered X-rays and the fact that uranium gave off rays that seemed like X-rays but were discernibly different. These discoveries and Curie’s investigative scientific abilities led her to develop methods for separating radium from radioactive residues in quantities large enough to be studied.

Related: 20 Biographies of Remarkable Women That You Need to Read

Soon, Curie was known internationally for her work on radioactivity. With her husband, she was awarded the Nobel Prize for Physics in 1903, and in 1911, she received the Nobel Prize for Chemistry. She was the first woman to win the Nobel, the first and only woman to have won it twice, the first female professor at the University of Paris, and the first woman to be entombed in the Pantheon in Paris based on her own merits. Unfortunately, as the study of radioactivity was wholly new, no one, including the Curies, understood the impact of it on the human body. Marie Curie died at on ly 66 from a rare form of cancer, caused by her proximity to radioactivity.

Henrietta Swan Leavitt

One of the extraordinary women covered in Whitlock and Evans’s book, Henrietta Leavitt was an American astronomer who worked as a “computer” (a human data analyst before electronic computers existed) at Harvard College Observatory during the late 1800s. During this time, Leavitt was assigned mundane tasks such as cataloging stars and monitoring their brightness, all while getting paid significantly less than her male coworkers. However, Leavitt’s detail-oriented job would help her contribute a scientific discovery that paved the way for future astronomy research.

While she was monitoring the varying brightness in stars, she began to realize that the stars she was looking at weren’t actually changing in brightness–rather they were just moving further away. When she began to dig deeper into this phenomenon, she found evidence that supported her theory and was able to create the first 3D map of the galaxy. This in turn helped scientists accurately measure the size of both our galaxy and the universe.

Unfortunately, Leavitt passed away at only 53 after being diagnosed with cancer. She had struggled with health issues for many years and had been hard of hearing since her early thirties. The "standard candle", a chosen light marker for gauging distance which is used today, is demarcated according to Leavitt's law.

Lise Meitner

Lise Meitner was an Austrian physicist who fled Nazi Germany in 1938, taking her experimental notes and results with her. When she found refuge in Sweden, she continued her atomic research with chemist Otto Hahn in secret. The duo’s combined knowledge of physics and chemistry helped them split an atom’s nucleus, discovering the process of nuclear fission.

When they published their evidence for the project, Hahn was given most of the credit, and he received a Nobel Prize for Chemistry in 1944, despite Meitner’s many, invaluable contributions. This oversight was somewhat amended in 1966 when Meitner was given the Enrico Fermi Award for her discovery and work in the field. Whitlock and Evans further elaborate on Meitner’s other scientific exploits and discoveries that went relatively unnoticed during her career in their book.

Maria Goeppert Mayer

Maria Goeppert Mayer was a German physicist who worked on a variety of projects that gained her a ton of recognition. When she first came to the United States during the 1930s, both her and her husband Joseph E. Mayer, a chemical physicist, were appointed positions at Columbia University. Despite this incredible opportunity, Maria wouldn’t receive a salary for quite some time.

Related: 18 Important Women in History You May Not Have Heard of

Mayer would move onto other experiments, including the Manhattan Project which tested the first ever nuclear bomb. She also became a professor at the University of Chicago in 1945, and was recognized for her accomplishments. It was during this time that she discovered that an atom’s nucleus has a shell and managed to develop a model of its structure. Her discovery created waves in the scientific community, and, in 1963, she became the second woman to receive a Nobel Prize in physics.

Elizabeth Blackwell

Elizabeth Blackwell was a pioneer in promoting women’s education in medicine. When she applied to Geneva Medical School, the admissions committee was hesitant to accept her. Rather than make their own decision, the dean put Blackwell’s admission up to a vote by the 150 students, and they unanimously decided to accept her as Geneva’s first female student. Two years later, in 1849, Blackwell graduated and became the first woman to receive a medical degree.

Blackwell had long dreamed of becoming a surgeon after receiving her medical degree. Unfortunately, in 1849, Blackwell was treating a baby with a highly contagious eye disease. She accidentally got some contaminated solution into her eye, causing an infection that took her sight—and ended her aspirations of becoming a surgeon. Blackwell went on to establish a medical school for women in London and become a specialist in midwifery.

Dr. Mae C. Jemison

In 1992, NASA’s Endeavour carried the first African-American female astronaut into space. Five years earlier, Mae C. Jemison had been accepted into the astronaut program. She had been inspired to try her luck after Sally Ride’s 1983 flight on the Challenger. Jemison’s program had 2,000 applicants. She was one of 15 accepted. In later interviews, Jemison often mentioned Star Trek's Lt. Uhura, played by Nichelle Nichols, as an inspiration for her career in space.

Related: 7 Facts About Black Women Who Shaped History

Before becoming an astronaut, Jemison was a medical doctor. She also worked for several years in the Peace Corps. Aside from her trailblazing career in NASA, Jemison is a dancer and holds nine honorary doctorates in science, engineering, letter and the humanities. She resigned from NASA in 1993, preferring to work at the intersection of social sciences and technology. Today, she is a Professor-at-Large for Cornell University.

Émilie du Châtelet

Du Châtelet, born in 1706, is unfortunately most frequently remembered for having an affair with Voltaire. But her scientific and philosophical contributions are more than worthy of recognition on their own merits. It's unclear when exactly du Châtelet's family noticed her marked intelligence, but by the time she was 10 years old, du Châtelet was having meetings with prominent scientists, arranged by her father. He also began engaging a number of tutors for du Châtelet, who justified the cost by becoming fluent in five languages by the age of 12.

Du Châtelet was engaging in serious philosophical debate by the 1730s, when she and Voltaire first met. The two worked on a book, Elements of the Philosophy of Newton, which popularized Newton's ideas about light and gravity. Du Châtelet also critiqued John Locke, published a paper on the nature of light and a book about physics which led to her joining the Academy of Sciences of the Institute of Bologna. Although her contributions are primarily remembered for popularizing others' ideas, du Châtelet was a talented scientist, writer, and philosopher in her own right.

Dame Jane Goodall

Jane Goodall is largely considered the world’s foremost chimp expert, primatologist, and anthropologist.

When she was just a year old, her father gave her a stuffed chimp. Even that early, Goodall felt a connection with the animal, which grew into a lifelong fascination and admiration. Because Goodall wasn’t as familiar with the typical rules and regulations of primatology, her approach to learning about chimpanzees’ social structure and lifestyle was quite different from that of her colleagues.

Goodall gave names to each of the chimps she studied and got to know them as individuals. This made it clear that the chimps did in fact have their own personalities and allowed Goodall to make new discoveries. For example, Goodall realized that chimpanzees were not vegetarians, as thought before. She was also the first to see a chimpanzee creating and using a tool: They broke off branches, stripped them of twigs, then used the branch as a utensil to scoop up termites.

Goodall has made it her life’s work to understand and protect chimpanzees. In 1977, she established the Jane Goodall Institute which supports chimp research and protection globally. Goodall has received a number of awards and honors, including the Order of the British Empire, for her work.

Rachel Carson

Carson and a coworker conducting research.

Photo Credit: Wikimedia CommonsRachel Carson is the best-known nature writer of the 20th century, if not of all time. Her work was the first to challenge the idea that humans impacting the environment always meant better for both humanity and environment. Carson began impacting people’s relationship with the environment during her very first job out of college. She was offered a job writing radio copy for the U.S. Bureau of Fisheries. Although not perhaps Carson’s original goal, she soon proved her ability to make the public interested in subjects like aquatic biology and the government’s impact on fisheries.

Related: Rachel Carson's Books Defined an Environmental Revolution

She became an advocate for the public’s right to education on climate change and its effects on the overall ecosystem. In her most famous book, Silent Spring, Carson questioned if humans have the right to control nature and who has the right to be the dominating voice on these issues. She also brought to light the many terrifying impacts of DDT, and many other chemicals, on the environment and people’s bodies.

Tiera Guinn Fletcher

This up-and-coming rocket scientist is just 22 years old. She graduated from MIT last year with a degree in Aerospace Engineering and a GPA of 5.0. Immediately after graduating, she was recruited by NASA to work under the title of Rocket Structural Design and Analysis Engineer on a rocket being built to send people to Mars. She’s won Good Housekeeping’s Awesome Women Award, been featured in Essence and The Huffington Post, and was a co-chair of the Black Women’s Alliance at MIT. We’ll be keeping our eyes on her work.

Mary Anning

Mary Anning began collecting fossils along the English Channel cliffs in the 1830s. The fossils she unearthed in the fossil beds embedded in these cliffs changed the course of scientific thinking about prehistoric life and the public's understanding of evolution of life on earth.

Most of her hunting was done during the winter, when landslides frequently exposed new fossils. This work was exactly as dangerous as it sounds: In 1833, she nearly died in a landslide that killed her dog. Despite the danger, Anning continued to pursue her fossils.

Anning had an unlikely beginning to her illustrious career. Born to a poor cabinetmaker in 1799, Anning’s family was never wealthy. Her father often took her and her younger brother Joseph out on fossil hunts to help support the family. After her father died in 1810, Anning became committed to the search as a way to support her family. Within a year, Anning and Joseph had discovered a large ichthyosaur skeleton, which they sold for 23 pounds (nearly $2,000 in modern terms).

Anning went on to discover a number of other significant fossilized skeletons. Yet she never fully participated in the scientific society despite her impressive understanding, at least partially because of the dominance of men. In 1830, geologist Henry De la Beche painted Duria Antiquior - A more Ancient Dorset, the first widely circulated visual representation of what prehistoric life on planet Earth might have looked like. His source of inspiration? The many fossils originally found by Anning.

Barbara McClintock

In 1983, Barbara McClintock won the Nobel Prize in Physiology and Medicine—the only woman to receive this award in her category unshared to date. McClintock was a cytogeneticist who studied chromosomes and how they change during reproduction. Working primarily with maize, McClintock was able to discover transposition: the ability of a cell to change a specific DNA sequence, therefore changing the identity or function of a cell.

Related: More Than a Scientist: The Lesser-Known Life of Sir Isaac Newton

Much of her work was ignored or dismissed for decades. DNA was barely understood, and other researchers could not understand how a cell could change its identity in such a way. By 1953, she even stopped publishing new work, so certain was she that her ideas would be ignored. Three decades later, she received the Nobel Prize, justifying her hard and groundbreaking work on genetics.

Rita Levi-Montalcini

Rita Levi-Montalcini was born in Italy. Part of a Jewish family, Levi-Montalcini was fired from the anatomy department of the University of Turin after a law was passed barring all Jews from university jobs. She made do, setting up a laboratory in her apartment to study nerve fibers. Her family eventually fled to Florence, assuming false identities to avoid the Holocaust.

After the war, Levi-Montalcini was able to go to the United States for research. She impressed her professor so much that he offered her a full time job, where she would go on to discover how a nerve growth factor dysfunction was a major symptom in cancer.

She was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology and Medicine in 1986 from the work she did with her colleague Stanley Cohen on NGF, both in cancers and in the brain. In 2002, she founded the European Brain Research Institute. Levi-Montalcini was also the first Nobel Prize winner to live to be 100.

This post is sponsored by Diversion Books. Thank you for supporting our partners, who make it possible for The Archive to celebrate the history you love.

Featured photo of Marie Curie: Alchetron; Additional photos: Guideposts / YouTube; Mark Schierbecker / Flickr (CC); Roma Sociale