On October 29, 1929, a decade of glamor, glitter, and progress came to a sudden end with a massive financial crash. With Black Tuesday's fall of the New York Stock Exchange came a number of destructive ramifications—from bank closures to soaring unemployment rates—which all paved the way for the decade-long Great Depression.

In the lead up to that fateful day, American stock prices had started falling after a long period of abnormal highs—most significantly when the London Stock Exchange crashed on September 20 of that year. But it wasn’t until October 24, 1929, now called Black Thursday, that full-blown panic began to sweep through Wall Street. Over the next few days, the Dow Jones Industrial Average would continue its swift decline, while fearful traders sold stocks at damaging volumes. As a result, prices changed too quickly for the ticker to record, leaving everyone with outdated and useless information. Several prominent bankers aimed to restore calm by buying up blue-chip stocks, though their actions only had a temporary effect. The worst was yet to come.

Related: Discover Labor Day's History and Origins from its Industrial Revolution Roots to Today

And on October 29, come it did. The desperate trading of roughly 16 million shares, a record-breaking number, led to the loss of billions of dollars and the official collapse of the New York Stock Exchange. Today, it's known as Black Tuesday—an inciting incident of the Great Depression. But how exactly did this happen?

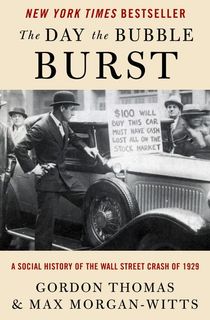

A crowd stands outside the New York Stock Exchange on October 24, 1929, just days before the collapse on Black Tuesday.

Photo Credit: Encyclopædia BritannicaThe end of World War I created a hunger for expansion, which, in turn, grew into an obsession with wealth and excess. Thus, the 1920s were “the Roaring 20s”, as the U.S. became the world’s leading financial power; new technologies came into play, and Western stock prices rose to unprecedented levels. With such a successful economy, it was impossible not to feel that the worst days were well and truly over.

It was the perfect environment for a credit boom—and, eventually, a shocking amount of debt—which also allowed overconfident consumers to buy stocks “on margin” (paying for a just small percentage of the value). Combined with overproduction, a flawed banking system, and a failing agricultural sector, a catastrophe like Black Tuesday was practically inevitable.

Related: Celebrate the Fourth of July With 8 Inspiring American History Books

The ramifications of the Black Tuesday crash would spread quickly through the industrialized world, even causing the German resentment that would become a breeding ground for Nazi thought and the beginnings of World War II, but on October 29, Americans were only aware of the devastating effects on their own pocketbooks. Although the extent to which the stock crash itself caused the Great Depression is and will be debated for years to come, there is no doubt of Black Tuesday's iconography as the flashpoint of the worst financial crisis suffered by the United States.

In their book The Day the Bubble Burst, authors Gordon Thomas and Max Morgan-Witts recount the events preceding, during, and following the crash through the eyes of those involved. Some of their subjects are prominent historical figures—such as J.P. Morgan and Henry Ford—while others are everyday citizens, but the result is a deeply humanizing study of one of history’s greatest financial disasters. Keep reading for an excerpt that places you at the center of the Black Tuesday drama, as veteran brokers, telegram deliverers, and bankers-slash-embezzlers scramble to make sense of the mayhem.

The panic carried uninterrupted into the early afternoon.

Steel was sinking toward $170. General Bridgeman and his staff were ankle-deep in paper.

At Post Five, eighty-six-year-old William Wadsworth—who had endured the 1907 panic and even earlier ones in the previous century—had never experienced such sustained fury. Men who normally treated the oldest broker on the floor with the deference his age and service demanded now hurled abuse at Wadsworth as they dumped rail stocks “by the bucketful.”

Nearly all of the 751 investment trusts had been virtually wiped out; the trusts had been founded, one bitter critic was to write, “on the same solid economic principles as the promotions of the Middle Ages financing the alchemists attempting to transmute base metal into gold. They were designed mainly to attract the spare dollars poor people had saved”

Most of those savings had now vanished in the whirlwind of selling.

Related: 26 Biographies of Remarkable Women That You Need to Read

Steel, the rails, the coals, the motors were swept away with the stocks of corporations, oil companies, and the other giants of industry.

Men wept openly in the Exchange. A few, doubtless for the first time in years, were driven to prayer, kneeling in impromptu supplication at the edge of the floor. Many went to nearby Trinity Church. It had totally filled for the thirty-minute service that began at noon, and would remain so for the rest of the day. For the first, and possibly only, time until now, Protestants, Catholics, and some Jews gathered together in Trinity, oblivious of its denomination, drawn there simply because it was a place of worship.

By early afternoon, Wall Street was blocked almost solid from Broadway to the river by an estimated ten thousand men and women. Rumors passed up and down the Street, bounced into adjoining streets, were enlarged, and bounced back into Wall.

Nobody knew what to believe; nobody knew how to behave.

There was no precedent for such a disaster.

By one o’clock, the orgy of selling on the Stock Exchange had risen to 12,652,000 shares.

It showed no sign of stopping.

Since early morning Homer Dowdy had been delivering telegrams along his route in Flint. In the past four hours he had dropped off more demands for margin than he had delivered altogether since Black Thursday.

Throughout the city every other available mailman was engaged in a similar task.

Related: 13 Remarkable Books About the Great Depression

It was the same in each city, town, and hamlet in America. The flood of telegrams had increased as the market crisis escalated.

In Flint, most of the margin demands were to cover the tumbling value of auto stocks.

Hundreds of employees in the body-building and assembly plants that surrounded the city had invested during the summer of 1929 in such shares. Many had bought individual $1,000 blocks for the minimum 10 percent deposit. Others formed consortiums, the members putting up $1,000 between them to buy $10,000 worth of stock in GM or Chrysler. Housewives had bought on margin. Businessmen extended their credit to speculate.

Seventeen-year-old Ed Love, whose uncle, Grant Brown, was president of the Union Industrial Bank, had recently asked his father whether he was worth a million dollars. His father said he was. And he was—on paper.

Related: Portraits in History: The Best David McCullough Books

The boy’s father was one of the first of the city’s “margin millionaires” to be wiped out.

Others followed.

Nobody knew what to believe; nobody knew how to behave.

By midmorning, Flint doctors—in common with physicians right across America—were having to treat cases of stroke and even heart attacks, brought on by the tension of “being caught in the market.”

On Saginaw Street, where Billy Durant had first ridden a mechanically propelled cart, Homer Dowdy observed men actually “wailing like lunatics, saying they wished the motor car had never been invented. They were ruined from their losses in GM.”

Outside brokerage offices he saw lines of “white-faced men who already knew what misery lay ahead.”

Dowdy had his own problems. His wife, Gladys, was now close to death; the burden of nursing a dying woman and bringing up three small children was taxing his resources. The world outside had come to mean less and less to the shy, lonely mailman locked into his own tragedy.

Then Dowdy heard something that jerked him back into that world and made him temporarily abandon his deliveries.

Someone ran past him shouting the Union Industrial Bank had closed its doors.

Jolan and Steve Vargo saw the doors shut when they were still a couple of hundred yards away from them. They started to run, joining the many others converging on the building.

Married just ten days, the young couple had put off going to the bank until now because “we had so many other things to do.”

And Steve had been “too busy” to ask Goldberger whether the attorney had learned why Jolan’s brother had been unable to withdraw his share of the trust fund.

Today, after lunch, Jolan and Steve had decided to go to the bank and settle what Steve assured his bride was a simple matter.

They arrived to find that the doors were firmly locked, a full hour before normal closing time. Steve had a ready explanation.

Several of his friends at work had received margin calls. He sympathized with them. Privately, he felt relieved he had the foresight to have placed his money in the bank.

Steve told Jolan the doors had undoubtedly been closed “on account of the trouble in New York.”

He led his wife away from the Union Industrial with the promise they would return another day; in the meantime, he insisted, their money was safer in the bank than anywhere.

It had been just before two o’clock when Frank Montague had finally decided what he must do. All morning he had followed news of the collapse in New York being relayed by telephone to Ivan Christensen.

At one-thirty Montague had estimated they owed the bank “around three million.”

Montague was short—and not for the first time—in his calculations. All told, he and his fellow conspirators had looted the bank for $3,592,000.

For thirty minutes Montague had agonized over what was the best course of action open to him. He had come to believe he had been “duped by the others. I had no idea we were in so deep.”

Montague decided there was no point in appealing to his coconspirators again. The moment had come.

As purposefully as he could, he walked the few feet to the desk of bank president Grant Brown.

In a halting voice Montague requested a private word with the president.

Related: 9 Best World War I Books

Brown led Montague into the directors’ room—where for so many months the “league of gentlemen” had planned their strategy at the strictly unofficial and very private late evening “board meetings.”

Montague began to confess.

Brown stopped him the moment Montague mentioned embezzling.

The president walked back into the bank.

The few customers there were quickly shown out. It was then that the bank doors were locked.

Standing in the center of the main banking hall, the stern-faced Grant Brown ordered all those who knew anything of the embezzlement to come to the directors’ room.

He rejoined Montague.

Behind him, Ivan Christensen quietly replaced the telephone receiver which, for almost four continuous hours, he had held to his ear.

Related: The Unbelievable Lives of Pilots Jessie Miller and Bill Lancaster

Brown and Montague sat in total silence, watching the closed door of the boardoom.

There was a hesitant knock.

“Enter.”

Into the room stepped Milton Pollock, ashen-faced, looking far older than his thirty-nine years.

Pollock closed the door and remained standing until Brown motioned him to sit. Pollock chose the chair he had always occupied at the illicit meetings.

There was another knock.

“Enter.”

The New York Stock Exchange trading floor, six months after the 1929 crash.

Photo Credit: WikipediaRussell Runyon and Elton Graham came in and also took up their usual places.

Next came a group of tellers: James Barron, Farrell Thompson, Robert McDonald, George Woodhouse, Clifford Plumb, Mark Kelly, David McGregor, and Arthur Schlosser.

They, too, silently took their accustomed seats.

Related: 11 Groundbreaking Books That Changed America

There was a pause.

Then, without knocking, Ivan Christensen and John de Camp entered.

Grant Brown stared frozen-faced at his deputy.

In strained silence the embezzlers waited.

There was another knock.

“Enter.”

Robert Brown, the president’s own son, the young teller widely tipped eventually to succeed his father to the bank presidency, stood, head down, in the doorway.

His father’s mouth fell open. In a low voice he spoke to his son.

“You, too, Robert?”

He nodded, eyes brimming, and walked into the room.

The distressing silence stretched on.

Finally Grant Brown asked whether there were any more to come.

John de Camp shook his head.

The president rose to his feet and walked back into the bank.

He told one of the staff to reopen the doors. Brown assured the anxious crowd outside that all was well; Flint’s only bank “panic” was over.

He returned to the boardroom. He locked its doors behind him and resumed his seat.

In a calm, clear voice he asked each man the same question. “Are you involved?”

Related: The Post Reporters Who Exposed the Truth About the Vietnam War

Each time he received the identical answer: Yes.

Grant Brown said nothing further. He went to a telephone on a side table and asked to be connected to Charles Stewart Mott in the General Motors Building in Detroit.

When he got through, Brown’s first words matched his magnificent control. “Mr. Mott, we have a problem here.”

Once Brown had identified that “problem” to the chairman of the bank’s Board of Directors, Mott immediately responded in similar fashion.

“Mr. Brown, I’ll be with you in no time.”

In New York the ticker kept running long after Crawford’s closing gong at 3 P.M. Every falling share it recorded helped sound the death knell of the New Era.

America, the richest nation in the world, indeed the richest in all history—its 125 million people possessed more real wealth and real income, per person and in total, than the people of any other country—was now paying the price for accepting too many get-rich-quick schemes, the damaging duels fought between bulls and bears, pool operations and manipulations, buying on overly slim margins securities of low and even fraudulent quality. The indecisive and sometimes misleading leadership from the business and political world had contributed to the nationwide stampede to unload.

At 5:32 P.M. the final quotation clicked across the tickers of a numbed nation. The tape’s operator signed off: TOTAL SALES TODAY 16,383,700. GOOD NIGHT.

Those millions of sales represented a loss in share value on the New York Exchange alone of some $10 billion. That was twice the amount of currency in circulation in the entire country at the time.

Eventually, the total lost in the financial pandemic would be put at a staggering $50 billion—all stemming from a virus that proved fatal on October 29, 1929: the day the bubble burst.

Want to keep reading? Download The Day the Bubble Burst today.

After the Black Tuesday crash, unemployment in the United States ballooned to 25% of the American working force—33% when farm workers were excluded. Farmers and the working poor were especially effected, as the Dust Bowl doubled the difficulties they were required to overcome. For those who managed to hold onto a job, wages declined sharply—or were simply no longer paid, like teachers in Chicago.

Mass migration from the Midwest to California began as people abandoned their homes and farms in hope of greener pastures. Across the country, many families split up as they lost their jobs and their homes.

Eventually, the combined forces of FDR's New Deal and the American entrance into WWII revitalized the American economy. The scars of this time, however, lasted far past the 1940s.

This post is sponsored by Open Road Media. Thank you for supporting our partners, who make it possible for The Archive to continue publishing the history stories you love.