When Alvin Cullum York was born in a log cabin in rural Tennessee, his farmer parents couldn’t have imagined that General Pershing would be calling him “the outstanding civilian soldier of the war” at York’s funeral some 76 years later or that Gary Cooper would win an Oscar for portraying his life in a 1941 film.

Much lay ahead for the infant, who was to live through some of America's most turbulent eras—and leave his mark on many of them.

Alvin York’s Youth

York’s mother and father were deeply impoverished subsistence farmers: His father also worked as a blacksmith during the off-seasons in an attempt to make ends meet. Alvin and his six brothers were rarely able to go to school as they were needed at home to assist with planting, harvesting, hunting, and laboring to ensure that the whole family—all 13 of them—could be fed by their farm.

When York was 24, his father died. Alvin’s two elder brothers had already left home, so he stepped up to become the primary provider of the family. Despite his lack of schooling, York supported his family through a variety of odd jobs as a laborer and construction worker, soon gaining a reputation as a highly skilled worker.

Related: 10 Back-to-School Books That Will Inspire Readers of All Ages

He also gained a less savory reputation as a drunk. After a hard day of work, York would be found in nearby saloons, where he frequently started fights. Despite his lack of temperance, York continued to attend church with his mother and family, deeply committed members of the Church of Christ in Christian Union, a pacifist and isolationist church.

After three years of hard work and harder carousing, York went to a revival meeting at his church. Although he had been a long-standing attendee, during this meeting, York experienced a moment of faith that he referred to as a conversion.

Related: 13 Books That Explore the History of World Religions

Thus, in 1914, he recommitted himself to his faith, which preached a purposeful disconnection with secular politics and violence. Despite this, in 1917, York, along with all other men between the ages of 21 and 31 in the United States, was compelled to register for the draft for World War I.

York’s Entry into Military Service

Although he would later deny it, York claimed a conscientious objector status on his draft card, writing “Don’t Want To Fight”. York submitted his draft card, objector status requested, in June 1917. Five months later, he was drafted—the army did not refuse conscientious objectors at the time, instead giving them duties which would not conflict with their beliefs.

Now 30 years old, York was sent to Camp Gordon in Georgia, where he joined the 328th Infantry Regiment. Although his objections to war continued, his service was heavily sought by his commanding officers, Captain Edward Danforth and Major G. Edward Buxton. No doubt they had heard of and seen his exemplary shooting. York had spent his childhood hunting turkeys and other game with his father and brothers, and had learned from his father, a “most wonderful shot”.

Related: Simo Häyhä: The Finnish Sniper Who Took Down 500 Soldiers Within 100 Days

Danforth, also possessed of a strong Christian faith, took it upon himself to convince York that God did not disapprove of violence at large. When Danforth combined his argument with a 10-day leave, he was able to get through to York, who came to believe that rather than expecting his pacifism, God would expect York to do his best to help win this war.

Alvin York, right, with his sister and mother in 1919.

Photo Credit: Wikimedia CommonsBy May 1918, York was in Europe, where his shooting ability and verve were put to the test. His division of the 328th Infantry, the 82nd, was made up of only newly drafted and conscripted soldiers. Their first major action was in the St. Mihiel Offensive, a three-day battle which showed German and Central Powers that the U.S. Army was one to be reckoned with.

York handled himself ably during the St. Mihiel Offensive. It was about a month later, though, that his actions would propel him to national acclaim. The 82nd was moved to the Western Front to take part in the Meuse—Argonne offensive, the single largest campaign in U.S. military history. Over 1.2 million U.S. soldiers took part in this offensive.

Related: John Basilone: The Marine Hero of Guadalcanal and Iwo Jima

York, by then promoted to corporal, three other non-commissioned officers, and 13 privates were sent by their commanding officers to infiltrate German lines on October 8, 1918. The battle had been ongoing for 12 days at this point, during which time the U.S. Army had failed to make the progress expected.

In hopes of minimizing damage done by the Germans, York and his company were to disable German machine guns. The German front lines had mowed down thousands of men, including the Lost Battalion. York wrote of passing the wounded and dying as they passed through to German territory:

“But God would never be cruel enough to create a cyclone as terrible as that Argonne battle. Only man would ever think of doing an awful thing like that…. And, oh my, we had to pass the wounded. And some of them were on stretchers going back to the dressing stations, and some of them were lying around, moaning and twitching. And the dead were all along the road. And it was wet and cold.”

Related: Léo Major: The "One-Eyed Ghost" Who Single-Handedly Liberated a Dutch Town

The next day, the group of men began their infiltration. The 17 men and their C.O., Sergeant Bernard Early, managed to take over the headquarters of the German unit in the area, despite machine gun fire from the opposing forces and the death of six of the men. With another three men wounded, York was suddenly in charge of a mere seven men as they continued their attempt.

York avoided the machine guns, then shot six men attempting to charge him with bayonets, continuing through the ranks. After exhausting his rifle’s artillery, he switched over to a small, semi-automatic pistol—but the Germans still couldn’t stop him.

The commanding officer of the opposing unit, First Lieutenant Paul Jürgen Vollmer, emptied his own pistol’s chambers attempting to take York down. With no bullets left to him, and the number of German soldiers killed or injured steadily increasing, Vollmer cut his losses and surrendered all remaining 132 German soldiers to York.

Related: Chesty Puller: The Life and Quotes of a Beloved Marine Legend

Upon York’s return with seven U.S. soldiers and 132 German captives, he was immediately promoted to sergeant. His actions were considered responsible for allowing the 328th Infantry to continue their attack on the Decauville railroad—which would eventually result in Allied forces breaking the rail line upon which German troops depended.

In addition to his promotion, York received the American Distinguished Service Cross; the French Croix de Guerre, Medaille Militaire, and Legion of Honor; the Italian Croce al Merito di Guerra; and nearly 50 other medals and decorations. His Distinguished Service Cross would be upgraded to the Medal of Honor in 1919. General Pershing himself presented York’s Medal of Honor.

Sergeant York After WWI

Upon his return to the United States, York’s fellow Tennesseans organized celebrations in his honor in New York, Hoboken, Washington, D.C., and Tennessee itself. York was thrilled to return home to his family, his farm, and his sweetheart, Gracie Williams. York and Williams were married within a week of his homecoming.

Since the tale of his exploits had traveled far and wide, York found himself inundated with requests for paid appearances, the rights to his life for movies and books, and advertising opportunities. But the humble soldier found all of this unappealing. He accepted the donation of a 400-acre farm by the Nashville Rotary and eschewed all other offers.

Related: 13 Remarkable Books About the Great Depression

Rather than accept money he felt unentitled to, Sergeant York began fundraising for charities—especially educational charities in Tennessee around his hometown. He developed the plans for and structure of an agricultural and vocational school open to all. The York Agricultural Institute opened its doors in 1926. Now called the Alvin C. York Institute, the high school is the only comprehensive, vocational school operated by a state government.

York focused primarily on making life in the rural regions of Tennessee kinder to its residents. Not content with his school, he also campaigned for a state highway, oversaw the creation of a manmade lake in local Cumberland Mountain State Park, served as Cumberland’s superintendent, and mortgaged his own farm during the Great Depression to ensure bus service for his school’s students.

As the Great Depression came to an end, and as Hitler rose to power in Germany, York found himself newly obsessed with happenings outside his home state. As he learned more about the rising tides across Europe, York began loudly calling for American intervention—long before such a stance was popular.

York stands on the hill in France where he captured 132 German prisoners.

Photo Credit: The U.S. National Archives / Flickr (CC)In 1941, over six months before Pearl Harbor, York gave a speech at the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier in Washington, D.C. He compellingly spoke about the need for action, saying that in World War I, “we won a lease on liberty, not a deed to it”. One of few publicly recognized interventionists at the time, his words caught President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s ear.

Related: 22 Eye-Opening Books About the Holocaust

Roosevelt frequently quoted him over the next few months, until the entrance of American forces and beyond. Upon that entrance, the now 54-year-old York immediately submitted himself for re-enlistment. Due to his age and increasingly poor health, he was sent around the country to support war efforts via bond drives and other charity initiatives rather than to the front lines.

Not long after the close of WWII, York’s health problems became debilitating. In 1954, he was confined to his bed after a series of strokes and a particularly brutal case of pneumonia. Despite this, he continued to keep up with current events. York believed that the only way to bring an end to the Cold War was to strike first in the Soviet Union and Korea.

In 1964, York passed away after a cerebral hemorrhage. He was 76 years old. York was survived by seven of his eight children and his wife, Gracie, who passed away 10 years later.

To the end, York was an honorable, hard-working, and charitable man. His contributions live on in memorials, monuments, public parks, and streets across the country—from Manhattan’s York Avenue to a movie theater on Fort Bragg’s property.

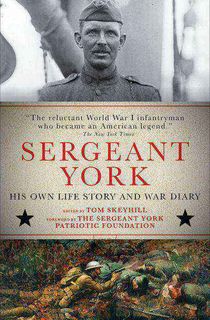

Want to learn more about Sergeant York's life? Download Tom Skeyhill's biography of Alvin York, written with his help.

Sources:

- Sergeant York, by Tom Skeyhill

- The Diary of Alvin York, Acacia

- WorldWar1.com

Featured photo: Wikimedia Commons