The American Civil War had been a tragedy that had the potential to spell the undoing of the United States. Tearing apart at the seams, here was a nation in need of attaining peace. After the fact, there were those military participants who felt it their responsibility to address the war from both moralistic and tactical points of view.

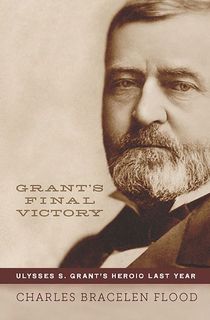

A man of unkempt appearances, and who was of the excessive practice of smoking cigars, certainly rivaling the later connoisseur Humphrey Bogart, was one such person. Ulysses S. Grant by name, he had been the great victor general in the war.

Another fellow, with fanciful whiskers and a disposition toward his pipe, was a kindred spirit of Grant's. This was Samuel Clemens, better known as Mark Twain, who held a storied history in relation to this divided American conflict. More than simply sharing a passion for offering their thoughts and memories regarding the Civil War, the two shared another intersecting point of correlation: camaraderie. The two were very good friends.

U.S. Grant studies papers in 1885, the final year of his life.

Photo Credit: Wikimedia CommonsA graduate of the famed Military Academy West Point, “Unconditional Surrender” Grant, who shared his first name with the legendary Greek warrior Odysseus of old, was a battle-hardened soldier by the time of the Civil War. After taking part in the Mexican-American War, Grant moved up the ranks of militaristic prestige over the Civil War until finally, President Lincoln appointed him to Lieutenant General in March 1864.

Grant overwhelmed the Confederate Army, leading to the surrender of Gen. Robert E. Lee in April 1865. Later, the war hero served two terms as U.S. President, from 1869 to 1877.

Related: 10 Civil War Battles That Shaped America's Bloodiest Conflict

Twain’s involvement in the war was neither as stout nor as glamorous. The war infiltrated his life as an immediate inconvenience to his livelihood. The author was first roped into the scheme of this conflict between North and South when the Union Army blockaded various parts of the Mississippi River, inhibiting his beloved job of piloting a riverboat.

As anyone familiar with the most popular works of Mark Twain can inform you, the man was enchanted by the beauty of traversing the river. The pace of the river was on a par with the beating of his heart and the pumping of his own blood. His Life on the Mississippi was taken away from him, and he was not too happy about it.

The incident, along with patriotism to his home state of Missouri, might have had some sway in his decision to join the Confederates under the command of Col. John Ralls. However, like many of his peers, his heart did not lie with the mainstream Southern sympathies. He soon abandoned this folly, making his way to his sister Pam who lived in St. Louis.

A few weeks' time found Samuel Clemens traveling westward-bound with his older brother Orion, whom President Lincoln had assigned the position of secretary to the governor of the Nevada Territory.

The Pony Express National Museum in St. Joseph, MI takes great pride in the history Mark Twain has with the Express. It was on July 26, 1861, that Samuel and Orion left the outpost via stagecoach, part of their travels together which Twain recounted in “Roughing It.”

One plaque at the museum notes his “dubious Civil War record,” stating that he was captured on two occasions by Union soldiers and had accusations brought against him. Namely, that he had informed the enemy of locations where Union boats maneuvered near the riverbank. Some believe that Clemens decided to write under the pseudonym “Mark Twain” once he reached Nevada with the intent to evade detection and execution as Union traitor Samuel Clemens.

In fact, both Twain and Grant were steadfast American patriots. Through his literature, Twain clearly displayed this virtue by his love of the natural landscape of the country and the liberties enjoyed within its borders. Grant, with equal zeal, showed his patriotism by fighting for his country's integrity and becoming a public servant in its highest government office.

Related: 6 Reasons the Union Won the American Civil War

In the settling years which came after the war, the two took to different career paths: the one to active politics, the other to his writing. The General, after his role in the Presidency and following a globetrotting adventure with his family, returned to the familiar town of Galena, IL.

However, the family soon moved to New York City, and Grant got involved in investing and co-founding the private banking firm Grant & Ward. Ward, unbeknownst to Grant, was running a Ponzi scheme that relied on the prestigious name of his partner. This was discovered 1884, causing a great Wall Street hubbub. Consequently, the Grant family was left wanting, in need of a decent income on which to live.

It was firstly out of necessity that the General considered writing his memoirs of the war. The editors of the Century magazine approached him expressing their plans to publish a series concerning the Civil War to be contributed by multiple authors. Although Grant initially declined, his monetary issues eventually led to accepting the commission.

Mark Twain sits center, flanked by George Alfred Townsend (left) and David Gray (right), circa 1871.

Photo Credit: Wikimedia CommonsEditors found the copy of his first draft to be too blunt and too similar to his official battle reports. Thus, Century associate editor Robert U. Johnson became the General's writing coach, and Grant caught on quickly, developing his own voice and style. “The result was a highly successful article, Grant's first conscious literary effort, that appeared in the Century in February 1885” (Pitkin 12).

Mark Twain, who had a background in journalism, also happened to have a Civil War memoir, “The Private History of a Campaign That Failed,” published by Century that same year.

In future work, Grant confided in his editors that he was spending hours on end, seven days a week, pouring himself into his writing. As if some conscience or id spurred him onward, he became wholeheartedly dedicated to this pastime. The seeds for a book-length compilation of memoirs were soon planted in Grant's mind by the Century. Of course, the magazine would practically demand to be the publisher of such a book.

However, Twain got wind of this news. When he heard of the measly royalties that Century intended on paying the retired General, he became indignant. Twain, via his publishing firm, offered a much more meaningful royalty scheme to Grant.

Related: 12 Books That Offer Perspectives on the Presidents

To this, Grant replied that “the book should go to the man who had first suggested it to him. 'General, if that is so, it belongs to me,' Twain responded. Grant did not understand until Twain reminded him that he had long ago urged the general to write his memoirs” (Pitkin 20). Ultimately, Grant did side with Twain, agreeing to have his memoirs published by Charles L. Webster & Co.

As he began work, Grant complained of a pain in his throat. It turned out to be quite serious. There were cancerous ulcers in his throat. Upon hearing of the severity of the matter, his friend Twain paid him a visit during which the novelist suggested the cause to be Grant's smoking. The doctor at hand did not consider it an appropriate comment.

Ulysses S. Grant fought on a new battlefront against time and dwindling personal health. He worked devotedly and passionately, exhausting himself in his literary labors. Miraculously, he finished the two volumes, published as the Personal Memoirs of U.S. Grant, and passed away on July 23, 1885.

Over the course of his life, Mark Twain was no stranger to grief. He lost friends, and he lost family members. In the years following the death of his friend, Clemens would lose several of his daughters and Olivia, his wife of more than three decades.

Four years after Grant's death, Twain's A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court was released. In its plot, Merlin is the antagonist to the narrator, ever seeking to thwart the ingenuity of the Yankee Hank Morgan. Arthur himself, on the other hand, apart from a period in which he walks the countryside with Morgan, is a somewhat minor personality. Twain’s book was an early contribution to a litany of literary works published over the next century that were preoccupied with the Arthurian legends.

But the most enlightening and noble characteristics of Twain's novel are not per se its comedy or even a focused narrative. The author's greatest mark embedded in the text of the novel comes in the form of his tangents, the little philosophical, sociopolitical concepts he shares with the reader. Two of the topics which directly come under fire of his criticism are slavery and the American Civil War.

Related: 7 of the Best American History Books

As for the first, Clemens offers a grim and gloomy depiction of the enslaved servitude practiced in medieval times. In the chapter “The Pilgrims,” the narrator, having observed a caravan of cruelly-treated individuals, vehemently relates, “If I lived and prospered I would be the death of slavery, that I was resolved upon...” During his life, U.S. Grant fostered a similar mentality, advocating for the rights of African Americans as well as those of Native Americans. Slavery then, being a serious social and moral issue coinciding with the Civil War era, was obviously frowned upon in many regards by both Grant and Clemens.

Later in A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Twain goes off on one of his informative economic tirades:

“I could remember how it was in the time of our great civil war in the nineteenth century. In the North a carpenter got three dollars a day, gold valuation; in the South he got fifty – payable in Confederate shinplasters worth a dollar a bushel... Consequently, wages were twice as high in the North as they were in the South, because the one wage had that much more purchasing power than the other had.”

Clemens, who had lost one of his favorite jobs on account of the war, was likely to have been acutely in tune with the economic differences between the two sides while traveling through the U.S.

The Civil War changed people's lives and how they interacted. The outcome and effects of the war have trickled down to the present day. Though their styles and methods differed in conveying their involvement in the war, both Grant and Clemens had a passion for giving their readers insight into what the war was like. Friends, authors, soldiers: they have provided their words as a historical testimony for posterity.

Learn more about Grant's waning years with Grant's Final Victory.

Sources: The Captain Departs, Thomas M. Pinker; Reader's Digest: The Story of America, Carroll C Calkin, et al editors, STLMag.com, NBCNews.com, The Guardian

Featured photo: Wikimedia Commons