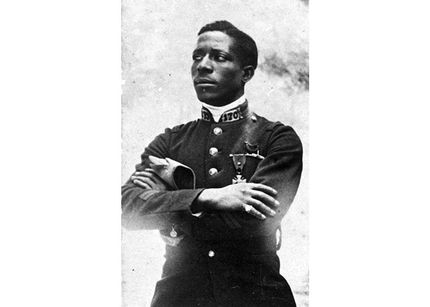

Eugene Bullard may have never flown for the U.S. Army, but that didn't stop him from becoming the first African American military pilot. Bullard’s father, who had been enslaved before the Civil War, and his mother, a Creek Indian, could have never imagined the accolades their baby boy, born in 1895, would achieve. The young boy’s future was bright: the “Black Swallow of Death” would go on to be awarded 15 war medals by the French Army.

But his youth was hardly one of promise—through no fault of his own. By the time he was 17, young Bullard had witnessed horrific acts of racism so common in Georgia at the time, including an attempted lynching of his own father.

Related: Black Patriots and Loyalists: An Untold Story of the Revolutionary War

After this, Bullard stowed away on a German freighter, aiming to follow in the footsteps of many African American immigrants. Believing that there was less prejudice to be encountered in Europe, Bullard traveled around Great Britain around the turn of the century, working primarily as a boxer and in a comedy troupe.

Eventually, Bullard made his way to Paris, where he promptly fell in love with the vibrant, bohemian city. Although the likes of Josephine Baker and James Baldwin were yet to step foot in France (or even be born, in Baldwin’s case), Paris had become a beacon for African Americans seeking a fresh start as early as 1803. Bullard had found his community at the age of 18.

Only a year later, everything changed as World War I broke out. Bullard was ready to take up arms to protect his new home. He wasted no time in joining the famed French Foreign Legion. The 19-year-old soon became well-known for his fighting capabilities, frequently besting enemy soldiers in hand-to-hand combat, and earning his nickname: the Black Swallow of Death.

Related: Pioneering Aviatrix Beryl Markham Flies "West with the Night"

Despite his ferocity—or perhaps because of it—Bullard was wounded during the Battle of Verdun. For his actions during the battle, Bullard was awarded with his first medals: the Croix de Guerre and the Médaille Militaire.

Bullard was severely injured. Medics believed that he may never walk again. Supposedly, this is when another American expat stepped in and made a wager with Bullard: He bet $2,000 that Bullard would not be able to become a pilot.

Whether the money or his own drive pushed him, Bullard was able to make good on that bet within a year. By October 1916, Bullard was back on his feet, and in service as an air gunner for the French Air Service. He began his flight training shortly after. On May 5, 1917, Bullard earned his wings. He was the first black fighter pilot in French—and American—history.

Bullard was sent to the Lafayette Flying Corps, joining 269 other Americans as they flew reconnaissance and pursuit missions along the Western Front. He would take part in over 20 combat missions over the next two and a half years, supposedly never failing to achieve the aim of his mission.

Related: This Former Slave Became The First African American West Point Grad

Less than two months after joining the Flying Corps, Bullard was promoted to a corporal. He continued to serve the French even after the United States joined World War I—he was not accepted to the American Expeditionary Forces after a medical examination due to his race. Bullard was discharged by France on October 24, 1919, nearly a year after the Armistice that marked the official end of World War I.

After his discharge, Bullard was awarded some 15 medals for his distinguished service. No doubt additionally disillusioned about America after his thwarted recruitment, Bullard returned to Paris, where he began working as a drummer in a nightclub.

He worked a hodgepodge of club jobs throughout the 1920s. Along the way, he met and married a wealthy French woman, with whom Bullard had two children. By the late 20s, Bullard was a giant amongst the French nightclub scene, palling around with Josephine Baker and Louis Armstrong.

Eventually, Bullard became the owner of a nightclub—where he would one day get sucked back into a global conflict. After the Second World War began, Bullard allowed the French government to spy on any German citizens who spent time in his club.

Bullard, kneeling at the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier in Paris in 1954.

Photo Credit: Wikimedia CommonsOnce Germans invaded France, Bullard rejoined the military. He had served with the 51st Regiment for just a month when he was seriously wounded at Orléans on June 15, 1940. He returned to the U.S. for the first time in nearly 30 years to recuperate.

Bullard made his new home in Harlem. A financial settlement from the French government for the destruction of his nightclub allowed him to purchase an apartment in the city, where he settled into a less star-studded life, limited by a chronic injury. He worked a variety of jobs in the late 1940s and 50s. He was amongst those attacked at the Peekskill riots at Paul Robeson’s civil rights fundraising concert.

Related: The True Glory of the 54th Massachusetts Regiment

After his return to the United States, Bullard was often alone. He and his wife had divorced in 1935 before the war. Though he had retained custody of his daughters, by the 1950s they were married and living in their new homes. He took a job as an elevator operator at 30 Rock, coming home to an empty apartment daily.

Two years before his death, Bullard was a guest on the Today Show. While wearing his work uniform, Bullard spoke of his years of service and his life abroad and back in the United States. Viewers across the country were touched deeply by his story, and Bullard received hundreds of letters of thanks.

Around this time, he was also knighted by General Charles de Gaulle, making him a Chevalier of the Légion d’honneur.

In 1961, Bullard passed away at the age of 66. He is buried in Flushing Cemetery, Queens, in the French War Veterans’ section.

His contributions were further recognized after his death. Eugene Bullard was inducted into the first class of the Georgia Aviation Hall of Fame in 1989, and in 1994, he was posthumously commissioned a second lieutenant in the U.S. Air Force—77 years after he was rejected due to his race.

Feature photos: Wikimedia Commons