When one thinks of the Revolutionary War, a simple tale of freedom from an overbearing and unwelcome government is typically the thing that springs to mind. But as with all simple tales, the true story of the American Revolution is far more complex.

One of those complexities can be found in the experience of black inhabitants of the American colonies. Though it is rarely brought up in historical discussions, black soldiers played a significant role on both sides of the Revolutionary War.

It’s no secret that, as America won its freedom from British colonial rule, that freedom only applied to a select portion of the people living there. For the enslaved blacks working for the rebellious Patriots, it may seem like fighting for the Loyalist cause was the obvious choice. After all, the Tories had promised black Loyalists their freedom once the Brits won—but many believed, perhaps too optimistically, that the Patriots would also free any black men who had been so committed as to fight for their freedom.

Related: 19 Facts About Black History That You Might Not Know

However they were convinced, there were plenty of both slaves and free black men fighting for the Patriot cause, either for monetary bounties, a chance at their own freedom, or through a draft. All in all, roughly 9,000 black soldiers fought on the side of the Patriots during the war, while an estimated 20,000 fought for the Loyalists.

One of the more famous black men amongst the Patriots was Crispus Attucks—a man martyred for the cause of American freedom. When the Boston Massacre broke out in March of 1770, Attucks was believed to be the first to fall.

Through other such iconic Revolutionary War battles as Lexington and Concord or the Battle of Bunker Hill, many slaves were freed so they could join the American militia—though the end of the war resulted in the re-enslavement of most of them. Peter Salem is among the more notable soldiers, serving for five years before actually moving on to a more peaceful life of freedom.

As for the Loyalists, many feared that arming enslaved Africans would result in broader slave revolts—so they began relegating black soldiers to spying and supporting British soldiers rather than allowing them to take part in battle.

However, in the final months of the war, British manpower was at an all-time low, and black forces were finally utilized in battle. Lord Dunmore’s Ethiopian Regiment was the most well known use of African soldiers, outfitting them in special uniforms proclaiming “Liberty to Slaves” across the breast. This regiment was heavily utilized in the south where the slave presence was the highest, and visible British acceptance of black soldiers spurred the Patriots to further embrace such efforts on their own side.

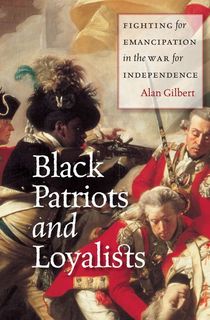

In author Alan Gilbert’s book, Black Patriots and Loyalists, a combination of primary sources and first-person accounts are used to flesh out the truth behind the American Revolution. Two wars were being waged on American soil, and freedom hung in the balance for both. In the excerpt of Gilbert’s work below, get a glimpse into the arguments used during wartime in favor of emancipation—nearly a hundred years before American slavery would end.

Read an excerpt from Black Patriots and Loyalists below, then download the book.

In the Second Treatise, Locke maintained that the oppressed may kill a tyrant who has dissolved the social contract and entered a state of nature with them, “as any lyon or tiger.” The people have no earthly law to appeal to, but only rebellion: “The conquered [by an aggressor], or their children have no court, no arbitrator on earth to appeal to. Then they may appeal as Jeptha did to Heaven, and repeat their appeal till they have recovered the native right of their ancestors, which was to have such a legislative over them, as the majority should approve and freely acquiesce in. If it be objected, this would cause endless trouble; I answer, no more than justice does, where she lies open to all that appeal to her.”

Philmore sanctions the “frequent attempts to get ‘the mastery’ that is, their liberty, or deliver themselves out of the miserable slavery they are in” of blacks in the Barbados: “all the black men now in our plantations, who are by unjust force deprived of their liberty and held in slavery, as they have none upon earth to appeal to, may lawfully repel that force with force, and to recover their liberty destroy their oppressors; and not only so, but it is the duty of others, white as well as black, to assist these miserable creatures, if they can.”

Allcraft recognizes that this reasoning could cause other nations justly to attack the English “man-traders”: “Suppose that a ship belonging to any other nation should see one of our ships on the coast of Guinea, full freighted with slaves, ready to sail, and coming up to her should insist upon their being all set at liberty, without any ransom, and, upon their demand not being complied with, should make an attack upon the English ship, and, getting the mastery of her, should unbind the slaves, and turn them ashore loose, to go wherever they list, according to your way of thinking, Mr. Philmore, this would be not only a justifiable, but likewise a good deed, a brave action.”

Applying Locke’s idea that revolution happens not for a single incident, but for a “long train of abuses, all pointing in the same direction,” Philmore contends: “For in truth we are now at war (we Englishmen, we Christians, to our shame be it spoken) and have been for above a hundred years past, without any cessation at all, at war and enmity with our own species, not with this or that particular nation.”

In Boston, James Otis, a lawyer and Patriot leader, adapted the words of Philmore, Montesquieu, and Locke. Hearing Otis speak in 1761, John Adams likened him to the prophets “Isaiah and Ezekiel united,” “a flame of fire.” Otis, too, integrated into political theories of freedom and independence the idea of slave rebellion; his was “a dissertation,” in Adams’s words, “on the rights of man in a state of nature [as] an independent sovereign, subject to no law but the law written on his heart.” “No Quaker in Philadelphia,” Adams added, “asserted the rights of negroes in stronger terms.”

Related: 10 Revealing Revolutionary War Books

But Adams took no delight in Otis’s extension to emancipation of the ideas that were to drive the American Revolution for independence. Instead, he feared the “consequences” that could be drawn from equality: “[I] shuddered at the doctrine he taught; and I have all my lifetime shuddered, and still shudder at the consequences that may be drawn from such premises.” Naming slave owners’ dread, Adams insisted: “Shall we say, that the rights of masters and servants clash, and can be decided only by force? I adore the idea of gradual abolitions! But who shall decide how fast or how slowly these abolitions shall be made?”

Published in 1764, Otis’s The Rights of the British Colonists Asserted and Proved passionately invoked the character of British law, which protects the liberties of each citizen; he identified the American protests against British policies with the English Revolution of 1640, which resulted in Parliament’s triumph over the tyranny of Charles I: “That the colonists, black and white, born here, are free-born British subjects, and entitled to all the essential civil rights of such, is a truth not only manifest from the provincial charters, from the principles of the common law, and acts of parliament; but from the British constitution which was reestablished at the revolution, with a professed design to secure the liberties of all the subjects to all generations.”

Otis repeatedly speaks of the “good, loyal and useful subjects” of the king, “black and white.” He links imperial theft of property—taxation without representation—to bondage: “In a state of nature, no man can take my property from me, without my consent: If he does, he deprives me of my liberty, and makes me a slave.”

Want to keep reading? Download Black Patriots and Loyalists.

Unfortunately, following the close of the Revolutionary War, African Americans would not gain their freedom for another 80 years. As previously stated, most of the black soldiers fighting for the Patriots were returned to a life of slavery, and those fighting for the Loyalists didn’t fare much better. Those who found freedom after fighting for the British were relocated to London and Nova Scotia where they faced heavy discrimination. Very few black soldiers benefited from the military after the war, with most veterans dying before seeing any hint of a pension, and with Congress turning around to forbid their presence among the military.

But their efforts were not for nothing. First and foremost, black forces had proved themselves as valuable and formidable wartime assets. But beyond that, the conversation of emancipation that stirred among the Revolutionary War could not be quieted. Though progress would be slow to come, their re-ignited efforts in the Civil War would turn the tides of history yet again.

This post is sponsored by Open Road Media. Thank you for supporting our partners, who make it possible for The Archive to continue publishing the history stories you love.

Featured photo: Alchetron