When it comes to fascinating lives, Beryl Markham's is particularly novel-worthy. Abandoned by her mother at the age of four, she moved from England to Kenya—where her horse trainer father set up his own farm. In the town of Nojoro, she developed an insatiable hunger for adventure—forming a vibrant daily routine of horse-riding, spear-hunting, and playing with a young Kipsigis warrior. At 17, she even became the first woman to obtain an official horse training license in Africa.

But her greatest claim to fame was yet to come. Thanks to the influence of two pilots—her instructor, Tom Campbell Black, and her sometimes-lover, Denys Finch Hatton—Beryl became a pilot herself in 1931. Five years later, she completed her record-breaking, east-to-west solo flight across the Atlantic, securing her place in the aviatrix hall of fame alongside Amelia Earhart. And while fuel-related issues forced Markham to land in Nova Scotia and not her planned New York destination, it was still an accomplishment that catapulted her and her subsequent memoir to global fame.

Beryl Markham passed away in 1986 at the age of 83.

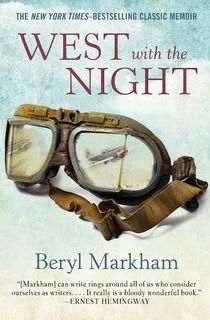

Photo Credit: AlchetronPublished in 1942, West with the Night is Markham's own account of her Kenyan childhood, her equine career, and her aviation achievements. But even though it was a literary success upon its release, it was soon dwarfed by the chaos of World War II. The book remained out of print until the early 1980s—by which point Markham had returned to Africa and racehorse training, but was living in poverty—when a series of rediscovered letters brought it back into the spotlight. The person behind the correspondence? Ernest Hemingway, whom Markham had met while scouting game in 1934.

"Did you read Beryl Markham's book, West with the Night? ...She has written so well, and marvelously well, that I was completely ashamed of myself as a writer. I felt that I was simply a carpenter with words, picking up whatever was furnished on the job and nailing them together and sometimes making an okay pig pen," Hemingway famously wrote. "But this girl, who is to my knowledge very unpleasant and we might even say a high-grade bitch, can write rings around all of us who consider ourselves as writers ... it really is a bloody wonderful book."

The ensuing publicity led to the memoir's republication and, today, it's considered a classic book on adventure and the outdoors. But as with so much of Markham's life—from her potentially illegitimate son with a Windsor royal to her love triangle involving the author of Out of Africa—her memoir is also shrouded in rumor. Some claim her journalist third husband wrote it; others insist every word is hers.

Either way, West with the Night is a gripping, beautifully written book that gives us insight into historical Kenya, aviation, and a truly remarkable woman of the early 20th century. Keep reading for an excerpt of the titular chapter in which Markham describes her legendary flight across across the Atlantic Ocean...

Record flights had actually never interested me very much for myself. There were people who thought that such flights were done for admiration and publicity, and worse. But of all the records—from Louis Blériot’s first crossing of the English Channel in nineteen hundred and nine, through and beyond Kingsford Smith’s flight from San Francisco to Sydney, Australia—none had been made by amateurs, nor by novices, nor by men or women less than hardened to failure, or less than masters of their trade. None of these was false. They were a company that simple respect and simple ambition made it worth more than an effort to follow.

The Carberrys (of Seramai) were in London and I could remember everything about their dinner party—even the menu. I could remember June Carberry and all her guests, and the man named McCarthy, who lived in Zanzibar, leaning across the table and saying, ‘J. C., why don’t you finance Beryl for a record flight?’

I could lie there staring lazily at the ceiling and recall J. C.’s dry answer: ‘A number of pilots have flown the North Atlantic, west to east. Only Jim Mollison has done it alone the other way—from Ireland. Nobody has done it alone from England—man or woman. I’d be interested in that, but nothing else. If you want to try it, Burl, I’ll back you. I think Edgar Percival could build a plane that would do it, provided you can fly it. Want to chance it?’

‘Yes.’

I could remember saying that better than I could remember anything — except J. C.’s almost ghoulish grin, and his remark that sealed the agreement: ‘It’s a deal, Burl. I’ll furnish the plane and you fly the Atlantic — but, gee, I wouldn’t tackle it for a million. Think of all that black water! Think how cold it is!’

Related: Fly Girls: The Daring Women Who Competed in Airplane Races During the Early 1900s

And I had thought of both.

I had thought of both for a while, and then there had been other things to think about. I had moved to Elstree, half-hour’s flight from the Percival Aircraft Works at Gravesend, and almost daily for three months now I had flown down to the factory in a hired plane and watched the Vega Gull they were making for me. I had watched her birth and watched her growth. I had watched her wings take shape, and seen wood and fabric moulded to her ribs to form her long, sleek belly, and I had seen her engine cradled into her frame, and made fast.

The Gull had a turquoise-blue body and silver wings. Edgar Percival had made her with care, with skill, and with worry—the care of a veteran flyer, the skill of a master designer, and the worry of a friend. Actually the plane was a standard sport model with a range of only six hundred and sixty miles. But she had a special undercarriage built to carry the weight of her extra oil and petrol tanks. The tanks were fixed into the wings, into the centre section, and into the cabin itself. In the cabin they formed a wall around my seat, and each tank had a petcock of its own. The petcocks were important.

‘If you open one,’ said Percival, ‘without shutting the other first, you may get an airlock. You know the tanks in the cabin have no gauges, so it may be best to let one run completely dry before opening the next. Your motor might go dead in the interval—but she’ll start again. She’s a De Havilland Gipsy—and Gipsys never stop.’

I had talked to Tom. We had spent hours going over the Atlantic chart, and I had realized that the tinker of Molo, now one of England’s great pilots, had traded his dreams and had got in return a better thing. Tom had grown older too; he had jettisoned a deadweight of irrelevant hopes and wonders, and had left himself a realistic code that had no room for temporizing or easy sentiment.

‘Think of all that black water! Think how cold it is!’

‘I’m glad you’re going to do it, Beryl. It won’t be simple. If you can get off the ground in the first place, with such an immense load of fuel, you’ll be alone in that plane about a night and a day—mostly night. Doing it east to west, the wind’s against you. In September, so is the weather. You won’t have a radio. If you misjudge your course only a few degrees, you’ll end up in Labrador or in the sea—so don’t misjudge anything.’

Tom could still grin. He had grinned; he had said: ‘Anyway, it ought to amuse you to think that your financial backer lives on a farm called “Place of Death” and your plane is being built at “Gravesend.” If you were consistent, you’d christen the Gull “The Flying Tombstone.”’

I hadn’t been that consistent. I had watched the building of the plane and I had trained for the flight like an athlete. And now, as I lay in bed, fully awake, I could still hear the quiet voice of the man from the Air Ministry intoning, like the voice of a dispassionate court clerk: ‘ … the weather for tonight and tomorrow … will be about the best you can expect.’ I should have liked to discuss the flight once more with Tom before I took off, but he was on a special job up north. I got out of bed and bathed and put on my flying clothes and took some cold chicken packed in a cardboard box and flew over to the military field at Abingdon, where the Vega Gull waited for me under the care of the R.A.F. I remember that the weather was clear and still.

Jim Mollison lent me his watch. He said: ‘This is not a gift. I wouldn’t part with it for anything. It got me across the North Atlantic and the South Atlantic too. Don’t lose it — and, for God’s sake, don’t get it wet. Salt water would ruin the works.’

“Brian Lewis gave me a life-saving jacket. Brian owned the plane I had been using between Elstree and Gravesend, and he had thought a long time about a farewell gift. What could be more practical than a pneumatic jacket that could be inflated through a rubber tube?

‘You could float around in it for days,’ said Brian. But I had to decide between the life-saver and warm clothes. I couldn’t have both, because of their bulk, and I hate the cold, so I left the jacket.

Related: The Unbelievable Lives of Pilots Jessie Miller and Bill Lancaster

And Jock Cameron, Brian’s mechanic, gave me a sprig of heather. If it had been a whole bush of heather, complete with roots growing in an earthen jar, I think I should have taken it, bulky or not. The blessing of Scotland, bestowed by a Scotsman, is not to be dismissed. Nor is the well-wishing of a ground mechanic to be taken lightly, for these men are the pilot’s contact with reality.

It is too much that with all those pedestrian centuries behind us we should, in a few decades, have learned to fly; it is too heady a thought, too proud a boast. Only the dirt on a mechanic’s hands, the straining vise, the splintered bolt of steel underfoot on the hangar floor — only these and such anxiety as the face of a Jock Cameron can hold for a pilot and his plane before a flight, serve to remind us that, not unlike the heather, we too are earthbound. We fly, but we have not ‘conquered’ the air. Nature presides in all her dignity, permitting us the study and the use of such of her forces as we may understand. It is when we presume to intimacy, having been granted only tolerance, that the harsh stick falls across our impudent knuckles and we rub the pain, staring upward, startled by our ignorance.

‘Here is a sprig of heather,’ said Jock, and I took it and pinned it into a pocket of my flying jacket.

There were press cars parked outside the field at Abingdon, and several press planes and photographers, but the R.A.F. kept everyone away from the grounds except technicians and a few of my friends.

The Carberrys had sailed for New York a month ago to wait for me there. Tom was still out of reach with no knowledge of my decision to leave, but that didn’t matter so much, I thought. It didn’t matter because Tom was unchanging—neither a fairweather pilot nor a fairweather friend. If for a month, or a year, or two years we sometimes had not seen each other, it still hadn’t mattered. Nor did this. Tom would never say, ‘You should have let me know.’ He assumed that I had learned all that he had tried to teach me, and for my part, I thought of him, even then, as the merest student must think of his mentor. I could sit in a cabin overcrowded with petrol tanks and set my course for North America, but the knowledge of my hands on the controls would be Tom’s knowledge. His words of caution and words of guidance, spoken so long ago, so many times, on bright mornings over the veldt or over a forest, or with a far mountain visible at the tip of our wing, would be spoken again, if I asked. So it didn’t matter, I thought. It was silly to think about.

You can live a lifetime and, at the end of it, know more about other people than you know about yourself. You learn to watch other people, but you never watch yourself because you strive against loneliness. If you read a book, or shuffle a deck of cards, or care for a dog, you are avoiding yourself. The abhorrence of loneliness is as natural as wanting to live at all. If it were otherwise, men would never have bothered to make an alphabet, nor to have fashioned words out of what were only animal sounds, nor to have crossed continents — each man to see what the other looked like.

Related: 20 Influential Women in History You Need to Know About

Being alone in an aeroplane for even so short a time as a night and a day, irrevocably alone, with nothing to observe but your instruments and your own hands in semi-darkness, nothing to contemplate but the size of your small courage, nothing to wonder about but the beliefs, the faces, and the hopes rooted in your mind — such an experience can be as startling as the first awareness of a stranger walking by your side at night. You are the stranger.’

It is dark already and I am over the south of Ireland. There are the lights of Cork and the lights are wet; they are drenched in Irish rain, and I am above them and dry. I am above them and the plane roars in a sobbing world, but it imparts no sadness to me. I feel the security of solitude, the exhilaration of escape. So long as I can see the lights and imagine the people walking under them, I feel selfishly triumphant, as if I have eluded care and left even the small sorrow of rain in other hands.

It is a little over an hour now since I left Abingdon. England, Wales, and the Irish Sea are behind me like so much time used up. On a long flight distance and time are the same. But there had been a moment when Time stopped — and Distance too. It was the moment I lifted the blue-and-silver Gull from the aerodrome, the moment the photographers aimed their cameras, the moment I felt the craft refuse its burden and strain toward the earth in sullen rebellion, only to listen at last to the persuasion of stick and elevators, the dogmatic argument of blueprints that said she had to fly because the figures proved it.

So she had flown, and once airborne, once she had yielded to the sophistry of a draughtsman’s board, she had said, ‘There. I have lifted the weight. Now, where are we bound?’—and the question had frightened me.

We are bound for a place thirty-six hundred miles from here—two thousand miles of it unbroken ocean. Most of the way it will be night. We are flying west with the night.’

Want to keep reading? Download West with the Night, by Beryl Markham, today.

Featured photo of Beryl Markham: Wikipedia

This post is sponsored by Open Road Media. Thank you for supporting our partners, who make it possible for The Archive to continue publishing the history stories you love.