Queen Victoria is known for her long and influential reign over the United Kingdom. However, her 63 years on the throne were not without their peril. Over the course of her rule, Queen Victoria faced eight different assassination attempts.

Related: Behind the Crown: 12 First-Class Books About Royalty

Unlike previously secluded monarchs, Queen Victoria tried to build a relationship with the public. From a young age, she went on “journeys'' through different parts of the country, greeting all sorts of individuals. She continued to venture out in public after becoming Queen. While these carriage rides through London and the United Kingdom helped shape her public image, they also became the scene for a variety of assassination attempts.

The first of Queen Victoria’s assassination attempts came in 1840. Edward Oxford shot twice at the carriage carrying Queen Victoria and Prince Albert, as they left Buckingham Palace. Fortunately, Oxford missed the Queen, who was four months pregnant with her first child at the time. He was quickly apprehended, while the royal couple continued their ride through Hyde Park. In the trial that followed, Oxford was found to be insane, as he believed he was acting on behalf of a secret society called “Young England,” which in truth, was a creation of his own imagination.

Following Edward Oxford, John Francis attempted to assassinate Queen Victoria—twice. He stalked Queen Victoria's carriage on back-to-back days in 1842. His first assassination attempt stalled when his gun failed to fire. Returning to try again the next day, Francis’s second attempt failed when he missed his shot, at which point he was swarmed by undercover police officers who had been waiting for him to strike again.

Related: 5 Bloodthirsty Monarchs Who Slayed Their Way to the Throne

Through the decades, five more men attempted to kill the Queen. Thanks to frequent mishaps with their firearms and the help of bystanders, Queen Victoria escaped each attempt alive. Many of her would-be assassins, like Edward Oxford, Robert Pate, and Roderick Maclean were thought to be insane. However, others like William Hamilton, who hoped to be sent to prison after growing tired of being unemployed, and Arthur O’Connor, who hoped to intimidate the Queen into releasing Irish prisoners, attacked the Queen to pursue specific ends.

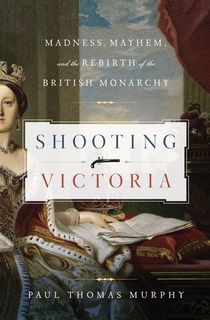

Shooting Victoria chronicles the many attempts on Queen Victoria’s life. Through a compelling narrative history, the unique account not only dives into each harrowing encounter, but also offers a new perspective on Queen Victoria, who came to be the namesake for an entire era.

Read an excerpt from Shooting Victoria below, then download the book.

Wednesday the 10th of June 1840 was fine and bright: perfect weather for an outing in Hyde Park. Edward Oxford dined with his sister early in the afternoon. His mother was still with her family in Birmingham; his brother-in-law was at work at the soda manufacturer. Perhaps Edward and Susannah talked about their father; it was his birthday that day. When they were done, Edward geared himself up just as he had over the past few weeks: he carefully placed his two pistols, loaded with powder and wadding, in his gray Gambroon trousers, and carefully placed red rags between hammer and cap. He also equipped himself with a knife. He was off to the shooting gallery, he told his sister—and on the way he would buy some linen for shirts, and some tea from Mr. Twining’s shop in the Strand.

He stopped first at Lovett’s, to take coffee and glance at the newspapers, as usual. If he followed habit and looked over the employment advertisements, he did so ironically; he knew now that pulling pints of ale was not in his future. He might have glanced at the Court Circular, to reassure himself that the Queen was in residence and following the usual routine. She was. Yesterday, she had met with her aunt Adelaide, the Queen Dowager; she had gone for an airing with Albert late in the afternoon; in the evening, she and Albert had attended the opera—Rossini’s Barber of Seville—with her half-brother, the Prince of Leiningen. Lovett, the proprietor, saw Oxford sitting there, but didn’t see the pistols bulging in his pockets: Oxford’s coat hid them. Oxford left, abruptly, without paying. He would never be coming back.

Related: 4 of the Craziest Assassination Attempts in U.S. History

Oxford doubled back past his home and past Bethlem, up Westminster Bridge Road, across the river and past Parliament and Whitehall, into the green heart of the metropolis: St. James’s Park, Pall Mall, and the Gates of Buckingham Palace, with Green Park and Constitution Hill in the distance. He joined the crowd milling about the Marble Arch—then in its original position as the front gate to Buckingham Palace*—everyone there hoping to catch a glimpse of the Queen or her Consort. Albert had left the Palace in the morning, visiting, as he had a month before, Woolwich Dockyard. The Queen was scheduled to go with him, and a royal salute had been planned, but on this morning she felt ill—quite possibly from morning sickness—so she stayed, and Albert went as her representative.

Albert was taking his first steps into public life. He had chaired, and given his brief speech to, the Anti-Slavery Society nine days before; writing it in German, translating it with Victoria’s help, and practicing it repeatedly and nervously before her. In the end, Exeter Hall was filled beyond its capacity of four thousand, and Albert’s slightly accented words were received with “tremendous applause.” Albert made a great success of his trip to Woolwich, as well: three thousand inhabitants of the town were on hand to cheer his coming. With his genuine interest in industry and manufacture—an interest that only grew with time, and would lead to the enormously successful Great Exhibition, in 1851—Albert was fascinated by the construction of a new warship, the 120-gun HMS Trafalgar, speaking with laborers and watching them at work. After an “elegant dejeuné” with the supervisor of the yard, he left to the “three hearty cheers” of the workmen, and was now riding in a carriage back to the Palace. The Queen had spent a quiet day in the Palace, her only engagement seeing Lord Melbourne in the morning; she awaited Albert’s return so that the two could go for their daily airing in Hyde Park. Oxford was there to see Albert’s carriage sweep up the Mall and through the palace gates. He knew who was in the carriage, and knew from whence it had come.

.jpg?w=32)

Under the title "God Saved The Queen!" this lithograph showed Edward Oxford shooting at Queen Victoria in 1840.

Photo Credit: Wikimedia CommonsAt around four o’clock, Oxford walked around to the north side of the Palace, a couple hundred yards up Constitution Hill. Invariably, when they took their regular airing, Victoria and Albert left the front gates of the Palace, turned sharply left, and traveled up the Hill, with the walls to the Palace gardens on their left, and the palings to Green Park on their right, in order to reach Hyde Park. The crowd was not as numerous on the hill as it was at the gate. Oxford paced back and forth beside the road, his hands inside his jacket, each gripping a pistol up under his armpits, giving him a bulging breast and a Napoleonic stoop. A number of bystanders saw him in this curious pose, but apparently thought little of it; they, like he, were focused on the gate down the Hill, from which they expected the little Queen and her Consort would soon emerge.

Related: 11 Beautiful Medieval Castles History Lovers Can Visit Today

At six, the gates opened and the procession emerged: two outriders, the Prince and the Queen in a droshky, a very low carriage that rendered the royal couple sitting alone fully visible to all. Two pair of horses pulled the carriage; riders sat upon the horses on the left side, responsive to Albert’s commands. Two equerries followed behind. The procession trotted out of the front gate of the Palace and up Constitution Hill, joined by many of the crowd at the gate, who were eager to lengthen their view of the royal couple. Few saw Oxford as the carriage approached—although one witness watched the odd, pacing figure, and watched Oxford stare at the carriage and “give a nod with his head sneeringly.” Among those on the path that day was the young artist-to-be John Everett Millais, then just eleven, and only months away from being the youngest student ever accepted to the Royal Academy Schools. He was there with his father and his older brother, John. The boys doffed their caps to the royal couple, and were delighted to see the Queen bow to them in response.

At that moment, Albert saw a “little mean looking man” six paces away from him, holding something that the Prince couldn’t quite make out: it was Oxford, pointing his pistol at the two, and in a dueler’s stance, firing a shot with a thunderous report that riveted the attention of all. Victoria, according to the Prince, was looking the other way at a horse and was stunned, with no idea why her ears were ringing. (She later told Lehzen that she thought someone was shooting birds in the park.) “I seized Victoria’s hands,” Albert wrote later, “and asked if the fright had not shaken her, but she laughed at the thing. I then looked again at the man, who was still standing in the same place, his arms crossed, and a pistol in each hand.” The carriage moved on several yards, and then stopped. Oxford looked around him to see the impression he was making and then turned back to the Queen and the Prince. He drew the pistol in his left hand from his coat, and adopted the highwayman’s pose he had been practicing for weeks, steadying his left hand on his right forearm, and taking careful aim at the Queen.

If he had expected the royal reaction to be sublime terror, he was mistaken. Victoria had not yet realized what the noise was, and Albert, writing to his (and Victoria’s) grandmother after the shooting, claimed that Oxford’s “attitude was so affected and theatrical it quite amused me.” Oxford later declared that he was equally amused with Albert, stating “when I fired the first pistol, Albert was about to jump from the carriage and put his foot out, but when he saw me present the second pistol, he immediately drew back.” Oxford cried out, “I have another here.” Now, the Queen saw Oxford and crouched, pulling Albert down with her, thinking to herself “if it please Providence, I shall escape.” Oxford fired a second time.

For an instant, silence; the carriage had stopped, and the crowd and the royal couple took a moment to register what had just happened. Then, shouts and screams. Oxford’s position made obvious by the smoke of the exploding percussion cap, the crowd converged upon him, some crying “Kill him!” The equerries and postilions stopped, and awaited a command. The Queen spoke to Albert, who called out to the postilions to drive on, and they did.

Victoria’s whispered command turned near-tragedy into overwhelming personal triumph. The decision to move forward—on to Hyde Park and the completion of their ride—and not to follow the instinctive impulse to go back and seek safety in the palace, was entirely Victoria’s, with her husband’s full agreement. The royal couple was surrounded by an escort of equerries, and the Metropolitan Police had stationed a number of officers at and around the Palace, three of whom ran immediately to Oxford at the sound of the first shot. But the royal couple had nothing like the police protection offered the monarch and other heads of state today, in which at the first inkling of an assassination attempt the protectors take charge and take steps to isolate their charges.

Related: These Bloody Days: The Tower of London in Tudor England

On the contrary, Victoria and Albert chose, for the next hour and then for the next few days, to expose themselves fully to her public. In doing so, she and Albert signified that absolute trust existed between them and their subjects, and demonstrated their belief that no would-be assassin could come between them. As Albert told his grandmother, he and Victoria decided to ride on in public “to show her public that we had not, on account of what happened, lost all confidence in them.” In return, they were showered with an immense and spontaneous outpouring of loyalty and affection, and enjoyed several days of national thanksgiving for the preservation of the monarchy—and the preservation of this monarch, and her husband and unborn child. In an instant, Lady Flora Hastings and the Bedchamber Crisis, and all suspicions about her German husband, were forgotten. Victoria’s personal courage and her unerring sense of her relationship with her people were responsible for it all.

.jpg?w=32)

Henry Tanworth Wells' 1887 painting depicted Queen Victoria hearing news of her ascension to the crown in 1837.

Photo Credit: Wikimedia CommonsAs she and Albert rushed toward Hyde Park, Victoria decided to alter her route. The news of the shooting, she knew, would travel with electric speed. Since very soon the Duchess of Kent in her mansion in Belgrave Square would hear the story, Victoria decided that she would personally tell her mother what had happened. Before they had reached the top of the hill, then, she again spoke to Albert; he directed the postilions to proceed at the usual pace through the Wellington Arch at the entrance of Hyde Park, and then veer south down Grosvenor Place to the Duchess’s residence, Ingestre House. They remained there until seven, and then set out to complete their turn around the Park.

Related: 20 Influential Women in History You Need to Know About

By this time, Oxford’s attempt was the single topic of conversation throughout London, and the Park had filled with Londoners of all social classes, the elite on horseback, all others on foot. The Queen’s aunt, the Duchess of Cambridge, was there with her children, as was Prince Louis Napoleon. All hoped to get a glimpse of the Prince and the Queen; all were by now aware of her “interesting condition,” and all (including, initially, Albert) were concerned that the shock of the attempt had had an effect upon the child; all yearned to demonstrate their loyalty and sympathy. The Times describes the joyous and spontaneous ceremony that followed:

. . . the apprehensions of the bystanders were in some degree relieved by seeing the Royal carriage containing the Queen and Prince Albert return along the drive towards the palace at about 7 o’clock. The carriage was attended by a great crowd of noblemen and gentlemen on horseback who had heard of the atrocious attempt in Hyde Park, and on seeing the carriage return accompanied it to the Palace gates, and testified their delight and satisfaction at the escape of her majesty and the prince by taking off their hats and cheering the Royal couple as they passed along. The joy of the populace was also expressed by long and loud huzzahs, and indeed the enthusiastic reception of her Majesty and the Prince by the assembled crowd must have been highly gratifying to them both. Her Majesty, as might well be supposed, appeared extremely pale from the effects of the alarm she had experienced, but, notwithstanding the state of her feelings, she seemed fully sensible of the attachment evinced to her Royal consort and herself by repeatedly smiling and bowing to the crowd in acknowledgement of their loyalty and affection.

In everyone’s mind—all, that is, except for Oxford’s—both the Queen and the Prince had shown an amazing amount of courage under fire. Once inside the Palace and in private, Victoria and Albert were able give in to the powerful emotions they had been experiencing during the shooting. By one account, Victoria burst into tears; by another, Albert held her and kissed her repeatedly, “praising her courage and self-possession.” Before long, they gathered themselves for their next audience: Victoria’s royal relatives and London’s leading politicians—Melbourne, Peel, John Russell, the Home Secretary Lord Normanby, on hearing of the shooting, had rushed to the Palace to see them. Victoria quickly rallied, and soon went to dinner “perfectly recovered.”

Want to keep reading? Download Shooting Victoria now.

[via: history.com]

This post is sponsored by Open Road Media. Thank you for supporting our partners, who make it possible for The Archive to continue publishing the history stories you love.

.jpg?w=3840)