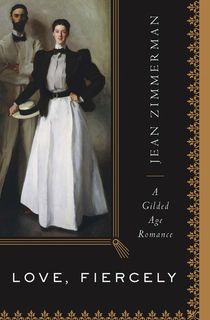

Wandering through the American wing of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, you'll eventually find yourself in a small room filled with paintings by John Singer Sargent. Although the room is built and formed to draw your eye to one iconic painting, you may soon find yourself gazing instead at the dual portrait of a couple hanging nearby. The woman's gaze falls directly on you, standing confidently, as her husband lingers in the background. This foregrounding, which would be unusual even today, is deeply striking for a portrait from 1897. It's no wonder that this portrait has led to an in-depth investigation of the people, Edith Minturn and Isaac Newton Phelps Stokes, shown within.

Author Jean Zimmerman, who had previously encountered Stokes's writing about the history of New York, became all the more deeply compelled by this painting and began investigating Minturn as well as Stokes. Stokes, who was a housing reform activist and progressive do-gooder, took no fainting lily as his wife. Edith Minturn was in many ways deeply similar to her husband. The pair, born to wealth, were highly educated, deeply connected, and invested in making the world better for the people around them.

After their marriage, Stokes focused his work to design alternatives to the tenements that were home to as many as two million poor immigrants and workers, frequently cramming a whole family into one small room. Encouraged by his wife, Stokes dedicated more of his time to this endeavor.

Meanwhile, Minturn–who took her husband's last name, but maintained control of her own wealth–began her own projects. Her work with the New York Kindergarten League was instrumental in popularizing the now-universal practice of sending children under the age of seven to school.

Related: War Bonds: True Stories of Love and Marriage During World War II

Although the couple waited until they were 28 to be married in 1895, they had met as children on Staten Island. Both came from business oriented, well-traveled families who wished to use their large fortunes to assist progressive causes. While Stokes's family owned much of Murray Hill, Minturn was the daughter of shipping magnate Robert Bowne Minturn, Jr. The beautiful, young heiress was well-educated and lived life intensely—leading to her brother's nickname “Fiercely”.

Minturn's vivacious personality and charitable inclinations led to Stokes's deep attraction and admiration for her. After some two years of pursuit, Minturn began to return his affection and the pair was married. Their fascinating love story is told amidst a glittering portrait of Gilded Age New York in Love, Fiercely.

Read on for an excerpt from Love, Fiercely, and then download the book.

In the spring of 1894, suffragists from around New York descended on Albany to plead their case at the state’s constitutional convention. Edith and family joined them: a New York Times story cited her by name, along with her mother and sister, as one of the notable New Yorkers coming together “in favor of striking the word ‘male’ from the Constitution.”

The suffragists served their petition at the secretary’s table, its half-million signatures tied in neat bundles with wide yellow ribbon. Nevertheless, the “Antis” won the day, with 98t representatives at the convention voting against, and fifty-eight for, the suffrage amendment. The Albany suffrage campaign headquarters shut its doors the day after the vote. Edith, May and Susanna trailed back to the city, defeated but unbowed. New York lawmakers would not approve female suffrage until 1917. But the 1894 campaign effectively thrust the women’s vote to the forefront of the progressive movement, and the pro-suffrage petition of almost 600,000 names provided indelible proof of the popular belief in equality.

Edith’s aunt Effie continued to inspire her protégée’s engagement with politics. The New York Consumers’ League, for example, had been founded in 1891 by Josephine Shaw Lowell. In fact, it would be difficult to find a progressive cause in the 1890s that didn’t have Aunt Josephine behind it. The Charity Organization Society was her brainchild—one of the premier philanthropic outfits of the day, it acted as an umbrella group for many forward-thinking concerns.

Related: The Unbelievable Lives of Pilots Jessie Miller and Bill Lancaster

The New York Consumers’ League became a model for similar leagues around the country, which ultimately assembled themselves into the still active National Consumers’ League. Edith served on the board of the organization, which used an early form of the economic boycott to force businesses to treat employees fairly, and put companies on a “white list” when they complied.

The goals of the league were the very opposite of lofty. In fact, they skewed consciously toward the humble and mundane. One of its initiatives revolved around the simple measure of providing chairs for shopgirls. At stores such as Macy’s, B. Altman and Arnold, Constable, female clerks were kept on their feet some ten to sixteen hours each working day. But even such a basic proposition as a chair provoked an angry response. The idea, fulminated the merchants, was “socialistic.”

Another project was stitched cotton underwear, made in dangerous sweatshops. It became the group’s pet crusade. Slowly, owners of garment companies complied with advocates’ demands, and just as slowly earned a place on the white list.

John Singer Sargent.

Photo Credit: Wikimedia CommonsHaving consumers vote with their pocketbooks, a common idea today, represented a progressive innovation. Edith and her cohorts explained diplomatically that it was not a case of blackballing those houses which failed to measure up, just that the league’s well-to-do, thousand-plus members would let their principles guide their purchasing decisions. The group’s motto neatly summed it up: “To live means to buy, to buy means to have power, to have power means to have duties.”

A later Consumers’ League project surveyed New York City’s candy industry, “from the little loft factory in the dirty side street turning out the cheapest grade of lollipop, to the large model daylight factory whose products are nationally advertised.” Using the leisure time of which many league activists enjoyed in generous supply, members engaged in the Gilded Age equivalent of sitdown strikes and the Internet flash mob, descending on the stores and refusing to budge until the owners agreed to comply with their demands.

Many humble women’s clubs and organizations of this period grew up to become engines for change, from lowly local tea-and-literature groups to the mighty Woman’s Christian Temperance Union, founded in 1874. The dichotomy was clear, at least to the reformers of the late nineteenth century. The American male in his natural state had a corrupt influence on society. Women were pure, moderate and, in Edith’s case, fiercely devoted to cleaning up the economic and political messes left by men.

Related: 32 Colorized Black and White Photos That Will Change How You Look at History

In 1894, Edith ventured to Delancey Street’s Guild Hall, on the gritty Lower East Side, to volunteer at the annual reception of the University Settlement Society. The society promoted the novel idea of bringing college graduate volunteers, men and women both, to help the working poor, addressing such basic immigrant needs as jobs, literacy and even bathing—the washed, in other words, assisting the great unwashed. The ultimate aim was to assimilate the polyglot multitudes of the tenements into the amorphous ideal of “life in America.” The volunteers, meanwhile, felt themselves rewarded with a sense of virtue that accompanied the gift of themselves.

Edith Minturn, then at the height of her world’s fair fame, lent a certain cachet to the event simply by pouring coffee and tea for the eager altruists. The targeted clientele, present only in spirit inside the Guild Hall itself, crowded the tenement-heavy neighborhoods outside its doors. The society gathered the usual suspects of progressive New York. Edith’s mother, Susanna, attended, as did Mary Scrymser, erstwhile chaperone of the mountain-wagon excursions some years before, and some two hundred other socialites. Edith shared her beverage station with the celebrated Richard Watson Gilder, an editor and poet who took an intense interest in social problems, and various other luminaries.

Edith with her sisters—Sarah May, Gertrude and Mildred.

Photo Credit: Wikimedia CommonsThe talk was, as always in these circles, of tenements. What was wrong with them, the unhealthiness of them, how they might be reformed. Many of Edith’s peers found becoming a wife the ideal opportunity to absorb themselves in the flourishing social life of New York, and the calls, balls, dinners and wardrobe adjustments that were certainly a part of her existence as well. But true to the spirit of a progressive age, Edith had discovered a passion for the needs of the disenfranchised, whether it be women denied the vote, shopgirls denied even a chair on which to sit, or the immigrant poor, whose aspirations to a better way of life became her most acute concern.

The University Settlement Society progressives revered as their patron saint the crusading photojournalist and author Jacob August Riis, who in 1890 had published his shockingly explicit and wildly successful exposé, How the Other Half Lives. Riis’s book combined images and text to place under a magnifying glass every sordid detail of New York ghetto life, from tumbledown shanties and living room sweatshops to basement saloons where the inhabitants of hell drowned their sorrows. Newton was deeply affected by Riis’s groundbreaking work, which seemed tailor-made to grab the attention of a young New York City heir, the comfortable denizen of a world replete with every aesthetic resource imaginable, who was just then beginning to toy with the idea that his newfound passion, architecture, could be a source of social good.

Columbia University was then located at 49th Street and Madison Avenue. The progressive spirit permeated the school like a wafting breeze. Newton studied under two well-known professors, W. R. Ware (late of MIT) and Alfred Hamlin. His architecture tutor was a burgeoning classical architect named John Russell Pope, who would go on to earn acclaim as the creator of the Jefferson Memorial in Washington, D.C.

Related: The Mystery of the Vanishing Amber Room

“During this time,” Newton would later remark, “I made up my mind that I was more interested in planning than decorating.”

Newton took his lead as a fledgling architect from reformers like Josephine Lowell, whom he consulted when he was in graduate school. Aunt Josephine held a sentimental and inspirational role for both Newton and Edith. Newton thought it was possible to significantly improve the plight of the poor by physically altering their habitat. He firmly believed in the necessity of better housing for the poor, remembering later his conviction as a young man that it was “one of the crying needs of the day,” and that it would be his particular mission to address that need.

“The design and promotion of better housing,” he stated in his memoir, “especially in our large cities, furnished as good an opportunity for useful service as any other profession or field of activity.” The paradox of a man accustomed to wandering through family mansions, yet investing himself in questions of urban squalor, must have been apparent to Newton Stokes, possessed as he was of sharp intelligence and sensitivity. Yet the architect in training wholeheartedly pledged himself to “take up the study of economic planning and construction, especially in its application to the housing of the working classes.”

But there was always the other side of the coin, too: the young architect considered that he had better get a couple of years at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris under his belt. An educational trip through Italy would not hurt either. Just in case he might someday be asked to prove his bona fides as an architect at the service of his own social class.

In 1894, Newton embarked, with Professor Joseph Howland Hunt, son of the powerhouse architect Richard M. Hunt, and seven of his former Harvard classmates, to spend “three delightful months” on the Continent. The young men whiled away their mornings walking among important buildings, sketching, measuring, drinking it all in, then took the afternoons for sightseeing and the evenings for dissecting one another’s work. A restorer in charge of mosaics at St. Mark’s in Rome horrified them when he shared his knowledge that many of the works had been finished off with a roller to smooth them out, ridding them of the precious irregularities of the hand-set work. A distinguished archaeologist, Rodolfo Lancianni, had the flooded subbasement of the Forum pumped out for Newton and his friends, so they could better examine the building’s ancient foundation.

Related: Black Tuesday: 1929's Stock Market Crash Signaled the Great Depression's Start

Newton’s primary regret was not taking home a carved marble mantel he saw in a shop and coveted—having been given money by his father for a “suitable purchase”—because his peers counseled him against lugging it from Florence onward. For a month, the men resided in the Palazzo Dario on Venice’s Grand Canal, with a private gondoletta and their own gondoliere. Right next door, at the Palazzo Barbaro Wolkoff, lived the singing sensation Eleonora Duse, whom they observed, all pale face and burning dark eyes, as she skillfully threaded her own gondola through the traffic of the dense green canal.

École des Beaux-Arts.

Photo Credit: Wikimedia CommonsIn October, Newton reached Paris, taking an apartment on the fifth and top floor of 176 Boulevard Saint-Germain, on the Left Bank. He hired a manservant named François, formerly a batman to a French military officer. François could not only keep house competently but service his master’s bicycle as needed. Five-course dinners for twelve were not out of the ordinary at Newton’s apartment, with François attending in immaculate livery.

Entry to the École des Beaux-Arts eluded Newton. On the entrance exam he made a bad showing. In preparing to retake it, he entered the atelier of Henri Duray, an architect who specialized in the design of apartment houses. This at least was somewhat akin to the “people’s housing” Newton knew he wanted to produce. He also attended lectures at the École, and even completed assignments given at the school.

While in Paris, Newton decided to find out firsthand how it felt to be part of the world he had pledged to better. He spent a night at Fredin’s, a flophouse or “night retreat.” Wearing an old suit, a peaked cap and a red bandanna around his neck, with mussed hair and a face smeared with charcoal, the Madison Avenue–bred young man descended a steep flight of steps from the dimly lit street. In the cellar, the Fredin residents sat on benches drawn up to plain wood tables. Each man had a straw-stuffed canvas bag that he folded his arms around to use as a pillow. When soup was distributed in dirty bowls, Stokes decided he could probably wait to eat back at home.

At the same time, the social season was on in Paris, and that meant fancy-dress balls, or in Newton’s case, balls attended by the artists and architects with whom he associated. Most of the people Newton knew attended the Bal des Quat’z’Arts. École des Beaux-Arts students banded together every year to put on the rowdiest spectacle possible, partying in the name of everything aesthetic and bohemian. Their antics were designed to shock the non-artistes, who watched the parade of decadent floats and displays as they made their way after midnight from the Moulin Rouge into the surrounding neighborhoods.

Related: Constance: The Untold Story of Oscar Wilde’s Wife

Revelers and spectators could expect un trop de exposed flesh, with gold and silver paint slapped on for emphasis. People were still talking about the efforts of the preceding year’s ball, in 1893. One float had depicted the last days of Babylon, with a nude blonde borne on a black velvet litter by a dozen stalwart “blackamoors,” followed by camels and more nearly naked women. Who knew what would happen at the ball in 1894?

Newton, though not officially enrolled at the École, nabbed a coveted ticket and wrote home to get a costume shipped to him. He asked for the black velvet dress of his mother’s that he’d worn for a costume ball at 229 Madison Avenue the previous winter. He was not a stranger to drag.

Edith Minturn and Newton Stokes. Two no-longer-so-young New Yorkers, their parallel lives surprisingly similar in their central sustaining beliefs. Shaping their selves so that when they were finally ready to meet as adults, they would make an engagingly synchronous couple. But at first, the two parts whittled so uncannily for a fit did not seem to match at all.

Want to keep reading? Download Love, Fiercely today.

Edith posed for John Singer Sargent twice but the first portrait, a typical formal-wear style, was scrapped. With his second attempt, Sargent wanted to capture Edith at ease, wearing her "street clothes". Edith was meant to pose next to a Great Dane, but when the dog became unavailable, Newton agreed to stand in its place.

The portrait—commissioned as a wedding gift for the couple—portrays Edith standing boldly in front of her husband. Newton stands solemnly behind, flaunting a beard and dressed in a relaxed fashion. The frame measures 7 feet tall and permanently resides in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The portrait does a wonderful job of capturing the couple at their prime, lively and active.

The couple had no biological children, but they did adopt a 3-year-old girl named Helen during their travels in India. The girl, a daughter of Raj Lieutenant Colonel Maldion Byron Bicknell and his wife Mildred Bax-Ironside, was given over to the Stokes, as the Bicknells did not wish to raise children in India.

In addition to his work on urban housing, Stokes also designed Columbia University's St Paul's Chapel, multiple structures at Yale, and various office buildings in New York, San Francisco, Seattle, and Providence.

Edith and Newton remained married until her death in 1937. Newton died seven years later, in 1944.

Featured photo: Wikimedia Commons