When Constance Lloyd first met budding writer Oscar Wilde, their mutual flirtation was immediate. In 1884, the pair married, and while they had a mostly happy marriage, both were fiercely independent and enjoyed socializing with their literary friends in Paris.

Often overlooked due to her husband’s success, Constance was a popular children’s author who revolutionized women’s dress and fiercely advocated for women’s rights. But all that changed in the spring of 1895, when Oscar Wilde was convicted of “gross indecency”—a term used to describe homosexual activity—and sentenced to two years in prison. Suddenly, Constance was forced into exile. She even changed the last names of her children in hopes of escaping the scandal imposed upon her family, before dying in 1898 at the age of 39.

Author Franny Moyle chronicles the tragic downfall of Constance Wilde in her biography. Excerpting numerous unpublished letters, many between Constance and her brother Otho, Moyle introduces readers to this exceptional woman whose charmed life ended far too soon.

Read on for an excerpt from Constance, and then download the book.

The ‘Echoes of Society’ column of the North Wales Chronicle carried a satirical sketch in its July 1884 issue that went like this:

Mrs Oscar Wilde – ‘Yes dear, dinner is ready. Which do you prefer, sunflower dried, or some toasted lily of the valley?’ Oscar – ‘Ah! Ahem! Is that all you have?’ ‘Oh no! There is a big dish of violets in the refrigerator.’ ‘My love haven’t you got anything to eat?’ ‘Eat! Eat! Why what do you mean?’ ‘I should like some beef and potatoes and bread and a bottle of ale, and some’ – But the bride of the aesthete had fainted.

When Constance married Oscar in May 1884, she became a celebrity. She also became an integral partner for her husband in what Oscar considered the next phase of his career. If as a bachelor he had lived life as the embodiment of Aesthetic principles, in marriage he saw the opportunity ‘of realising a poetical conception … to set an example of the pervading influence of art in matrimony’.

Since his return from America, Oscar had abandoned his silk breeches and long hair in favour of elegant suits and a short, curled coiffure. In doing so he had cast off any sense of boyishness that might formerly have been associated with his public persona. Marriage allowed him to develop this more mature character further in the public imagination. Instinctively Oscar understood the key to maintaining the interest of one’s public is to offer them change. Constance could at once provide this, as well as amplifying and extending his profile.

But this is not to suggest that Oscar’s and Constance’s marriage was some form of publicity stunt, or merely something intended to benefit Oscar solely. It was a happy coincidence that allowed him his new ambition to explore how Aestheticism, and the liberal thinking that attached itself to this artistic movement, might apply in marriage. Far more importantly, his feelings for Constance were rooted in what was, according to the couple’s friends, a very genuine love affair. Ada Leverson, one such friend, noted that ‘when he first married, he was quite madly in love, and showed himself an unusually devoted husband.’

On honeymoon in Paris they took reasonably priced rooms, no doubt with John Horatio and Aunt Emily’s words about the need for economy and careful housekeeping still ringing in their ears. Their apartment in the Hotel Wagram, rue de Rivoli, was ‘3 rooms, 20 francs a day, not dear for a Paris Hotel’, Constance explained to Otho. ‘We are au quatrième quite a lovely view over the gardens of the Tuileries.’

From here the couple would launch themselves out into Paris society on a daily basis and indulge themselves in art. They visited the annual Paris salon to see the work by Oscar’s friends that was on display: Whistler was showing Harmony in Grey and Green: Miss Cicely Alexander, as well as Arrangement in Grey and Black, No. 2: Thomas Carlyle, and the sculptor John Donoghue a bas-relief of a nude boy playing the harp. They went to the opera and to see Sarah Bernhardt in Macbeth, a production in which Constance witnessed ‘the most splendid acting I ever saw. Only Donalbain was bad. The witches were charmingly grotesque. The Macbeth very good, Sarah of course superb, she simply stormed the part.’ They held dinner parties and attended dinner, luncheon and breakfast parties by return. Constance met an array of new artistic people, among them the American artist John Singer Sargent. Then there was the French novelist Paul Bourget, the sculptor Donoghue (whom Oscar had befriended in America) and the writer Robert Sherard.

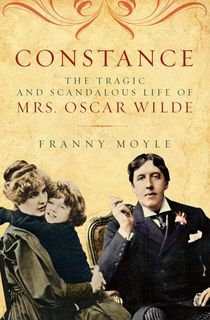

Oscar, Constance, and their son, Cyril, Wilde in 1892.

Photo Credit: WikipediaThe evening before he married, Oscar had had dinner with some of his closest married female friends, the painter Louise Jopling and the wife of his lawyer, George Lewis. They gave him advice on how a ‘young husband should treat his wife’. If they told him he should be romantic, full of grand gesture and spoil his new life-companion, then he followed their advice to the letter. Oscar was enormously extravagant towards Constance. If he ventured out with his Parisian friends while Constance remained behind to write letters, the minute he left her, Oscar would send bouquets of flowers back to their rooms and shower love gifts on her the moment he returned. He played the role of lover extremely well, and not just for Constance’s benefit. Robert Sherard found himself strolling along the Parisian streets with an Oscar full of nuptial joys and attempting to reveal in detail the delights of sleeping with his wife, details that Sherard squeamishly asked Oscar to desist from divulging.

But in spite of these grand gestures, even on his honeymoon Oscar displayed a characteristic that over the years of marriage to come would prove a thorn in Constance’s side. It is obvious that Oscar enjoyed being apart from his wife as much as he loved being with her. He would disappear, and she would be left alone to her own devices.

Oscar was attracted by danger. He loved experiencing low life and would seek out notorious street haunts, where he would immerse himself in another world. Even on his honeymoon Oscar and Robert Sherard ventured out to some of the low-life bars in Paris, such as the Château Rouge, a notorious criminal haunt, above which was Paris’s ‘Salle des Morts’. This was a room in which the city’s beggars and orphans, dropouts and cut-throats spent the night – a room full of ragged men who looked, in slumber, more like corpses than human beings, and upon whom Oscar gazed in horror and wonder.

Within a few months of their marriage Constance and Oscar would begin to talk about matrimony in unusual terms, consciously ‘modern’ in their approach to their new status. Adrian Hope recalled one dinner party with them in which Constance ‘said she thought it should be free to either party to go off at the expiration of the first year’. Oscar subsequently offered the proposal that marriage should be a contract for seven years, renewable as either party sees fit at the end of that duration.

It’s intriguing to speculate whether these expressions on both sides promoting some form of trial period in wedlock, or some notion that marriage need not be eternally binding, indicates that the marriage suffered some teething troubles. What is sure is that Oscar and Constance, like so many other Victorians, barely knew each other when they married. They had met many times, but nearly always in public situations. And Oscar had spent much of their six-month engagement away on his lecture tour.

It seems likely, given the many accounts of a genuine love affair between the two of them early on, that they simply suffered a kind of shock reaction to the adjustments each had to make to accommodate life with the other. Oscar must have been surprised to find, beneath the delicate exterior of his violet-eyed Artemis, a rather steely resolve and something of a short temper. Later in life, after Arthur Pinero had written his stage hit The Second Mrs Tanqueray, Oscar’s nickname for Constance would be Mrs Cantankeray. Constance, on the other hand, had to accommodate Oscar’s ego, his tendency to leave her alone and his utter uselessness with money.

In spite of this, the public profile that they presented was immediately, and for the next few years, fixed as one of utter union and single-minded purpose. If Oscar had an idea that there could be such a thing as an artistic marriage, then Constance was ready and prepared to explore it with him.

Want to keep reading? Download Constance now.

This post is sponsored by Open Road Media. Thank you for supporting our partners, who make it possible for The Archive to continue publishing the history stories you love.

Featured photos of Constance and Oscar Wilde: Wikipedia