When one thinks about the great military minds of the past, the idea that one of the most influential leaders would have a start in history and archaeology might come as a surprise. But T.E. Lawrence, popularly known as "Lawrence of Arabia" after the 1962 movie of the same name, would fit right in with us history buffs.

Thomas Edward Lawrence studied history at Jesus College before working as an archaeologist for the British Museum, chiefly in the north of Ottoman Syria. After the start of WWI, he volunteered to serve in the British Army and was stationed in Egypt, eventually being sent to Arabia on an intelligence mission where he became a liaison for the Arab Revolt.

The people he worked and fought with would become fond of Lawrence, as he developed a keen interest in the history and customs of the Arabian Peninsula. Emir Faisal, who suggested Lawrence dress as a Bedouin to solidify his acceptance and would become the King of Iraq, led alongside Lawrence, securing victories that would culminate in the capture of Damascus from Ottoman rule.

Related: 22 World War 1 Movies That Take Viewers into the Trenches

The on-screen portrayal shows Lawrence leading a charge directly into the Red Sea port of Aqaba, a vital strategic location for the Arab Revolt and Allied forces to claim before pursuing Damascus. In reality, the battle was fought about forty miles away, and Aqaba itself was taken with little resistance afterward.

The importance of the battle and Lawrence's involvement in it cannot be stressed enough, however. The Royal Navy had failed to take Aqaba from the sea on several occasions, and attacking from land seemed impossible due to nearly 200 miles of desert blocking the approach.

The idea of crossing that desert was ludicrous. Lawrence and Faisal counted on this approach being dismissed as such—and sent their troops out over the desert, suffering intense heat and dehydration before successfully attacking Turkish defenses from behind.

As strategic a leader as he was sympathetic to the Arab Revolt's cause, Lawrence's planning and provided intel was just as vital, if not more so, than his overseeing of the conflict itself.

The European Allied forces were considering capture of the port for their own economic gain, while the Arab insurgency could use Aqaba as a new foothold in spreading the insurgency. Furthermore, Lawrence knew that allied imperial powers had little intention of recognizing Arab independence after the war, with Britain, France, and Russia agreeing to a joint plan to split the territories of the Middle East once the conflict was through.

Relaying this secret information to Faisal, further cementing his reputation with the leader and binding the two men in a political conspiracy, the Arab Revolt set out to capture the port and legitimize the Arab insurgency.

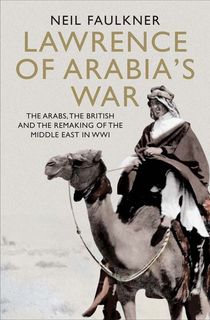

Archaeologist and historian Neil Faulkner's book Lawrence of Arabia's War shows just how instrumental Lawrence's leadership was in many battles, especially the one to take Aqaba. Drawing on 10 years of field research, Catch a glimpse of the historic roots of today's divided Middle East in the excerpt for Faulkner's book below.

Read an excerpt from Lawrence of Arabia's War below, then download the book.

Much hinged upon a recent arrival at Feisal’s headquarters at Wejh: Auda abu Tayi. Auda was the foremost fighting chieftain of the Howeitat, the tribe whose territory straddled the desert and semi-desert regions of southernmost Syria – the territory through which any Arab advance north would have to pass. Without Auda’s Howeitat, the Hashemites would remain bottled in the Hijaz for evermore.

Auda was about 50 in 1917, his black hair streaked with white, but he was still, reported Lawrence:

strong and straight, loosely built, spare, and active as a much younger man. His face was magnificent, even to its lines and hollows … He had large eloquent eyes, like black velvet in richness. His forehead was low and broad, his nose very high and sharp, powerfully hooked, his mouth rather large, and his beard and moustaches trimmed to a point, in Howeitat style, with the lower jaw shaven underneath.

Lawrence saw in Auda ‘a knight-errant’; he was more truly a figure from Homer.

His hospitality was sweeping … His generosity kept him always poor, despite the profits of a hundred raids. He had married twenty-eight times, had been wounded thirteen times, and in the battles he provoked had seen all his tribesmen hurt, and most of his relations slain. He himself had killed seventy-five men, all Arabs, by his own hand in battle … Of the number of dead Turks he could give no account: they did not enter his register.

A man of extremes, an Arab Achilles, he could fly into ferocious rages, when men would flee his presence as that of a ‘wild beast’, yet he loved to shout out stories against himself, invent others at the expense of his guests, and could at times be ‘simple as a child, direct, honest, kind-hearted, and warmly loved’. Auda lived life, and imagined life, as a saga: ‘His mind was stored with tales of old raids, and epic poems of fights, and he overflowed with them on the nearest listener. If he had no listener, he would very likely sing them to himself in his tremendous voice, deep, resonant, and loud.’

Related: 5 Dumb Military Tactics That Actually Worked

Auda’s leadership had raised the Abu Tayi clan to supremacy among the wider Howeitat tribe. He was rated ‘the greatest fighting man in northern Arabia’, and his followers became ‘the first fighters of the desert, with a tradition of desperate courage, and a sense of superiority which never left them while there was life and work to do … but which had reduced them from 1,200 men to less than 500 in 30 years.’ Lawrence logged the fighting strength of the Abu Tayi in 1917 at 535 camel-men and 25 horsemen.

He met Auda for the first time immediately upon his return to Wejh in April. The Howeitat chieftain drew back Feisal’s tent-flap and boomed out a salutation. Feisal rose to meet him. In Lawrence’s eyes they made ‘a splendid pair, as unlike as possible, but typical of much that was best in Arabia, Feisal the prophet, and Auda the warrior, each looking his part to perfection, and each immediately understanding and liking the other’.

Emir Faisal (center) at the Paris Peace Conference, accompanied by T.E. Lawrence (third from right) and others.

Photo Credit: Wikimedia CommonsTo Lawrence they must have seemed incarnations of the legends of the past. Liddell Hart, who knew Lawrence well after the war, thinks he saw in Auda ‘an inverted Crusading baron who seemed to have marched straight out of Lawrence’s former medieval dream-world to greet him’. But the dream obscured a harsher truth: there was perhaps more to Lawrence’s perception than he would have cared to admit. Feisal was the personification of a form of Arab nationalism distorted by Hashemite ambition and its dependence on British imperialism. Auda was a tribal patriarch, a warrior-chieftain, an outlawed robber-baron, a man rooted in traditions that owed nothing to the ideologies and movements of the modern world; he was a pre-modern who fought for glory, booty and honour. The dependence of ‘the prophet’ on ‘the warrior’ therefore had this deeper significance: it confirmed that Arab nationalism, uprooted from the barracks and cities of Syria, had become a withered weed of the desert, sustained only by British gold and Bedouin raiding. This must inform our answer to an old question: whose idea was the Aqaba campaign?

No definitive answer is ever likely to be given. Discussions were had and decisions made in the secret conclaves of Feisal’s command tent at Wejh in the spring of 1917. No official written record was made. Even had it been, the subtleties of interpersonal influence, often perhaps the fruit of prior conversations, might easily have gone unnoticed. What we can say is this. Other British officers, in deference to both conventional military wisdom and the promptings of their French allies, were unanimous in urging Feisal to remain focused on operations in the Hijaz. Feisal himself was a somewhat timid politician; ambitious, for sure, and a charming diplomat and coalition-builder, but neither a great commander gifted with wide strategic vision, nor a desert warrior with fire in his belly in the Auda mould; he was, in one British officer’s judgement, ‘a man who can’t stand the racket’. In any case, the state-building ambition of Feisal and his brothers – not to mention the Ottoman-Arab officers they recruited to their cause – inclined them to prioritise building up the strength of their regular army and waging conventional warfare; they needed their tribesmen, but they were not guerrilla leaders by choice. The tribal sheikhs who joined them, on the other hand, were not so much nationalists waging a war of liberation as traditional desert raiders with followings inflated by foreign guns and gold. Because of this, as long as the war lasted, Lawrence was ever anxious that the tribesmen would be diverted from their military objectives to softer, more lucrative targets; and dispersal laden with loot after a successful operation was a perennial problem.

Related: Explore History's Deadliest Diseases

Lawrence seems to stand outside this tangle of interests. As an officer, he was not a regular but a wartime maverick, one much given to deep reading and reflection, and endowed with a first-class brain. As a latter-day romantic, he idealised the Bedouin as a special people, untainted by modernity, unspoilt by materialism and corruption, men in the mould of the legendary heroes of medieval literature. As an Arabist, a man who knew the language, the people and the region, a man who now counted many Arabs as comrades-in-arms, he was appalled by the secret diplomacy to which he was privy. Lawrence straddled boxes, fitting into none, and thus was uniquely placed to think outside them all. He had encouraged the move to Wejh. He had reconfigured the war in his fevered head at Wadi Ais. And now he was the shy, quiet, shadowy, almost imperceptible mover and shaker who gently guided other men in the direction of their inclinations. Towards Aqaba. And then Damascus.

A photo taken by T.E. Lawrence in the desert.

Photo Credit: Wikimedia CommonsAttempts to deny his influence fall flat. He was, after all, in his capacity as liaison officer, the plug in the socket connecting Feisal’s Arab Northern Army to its British supply-chain. But he was, of course, much more, for he had forged a special relationship with ‘his’ leader, based on a mix of cultural empathy, sound advice and proven political loyalty. The last must have had exceptional significance. While other British officers were party to a conspiracy to keep the Sykes–Picot Agreement secret – Clayton, Newcombe and Wilson all reported, with varying degrees of disquiet, that Hussein had no knowledge of its details – Lawrence had divulged what he knew to Feisal. Now, though, he went much further: he planned a daring deep-penetration raid designed to project an Arab commando force through the deserts of northern Arabia into southern Syria, there to raise the local tribes and descend upon Aqaba from the landward side. The effect would be to turn the Wadi Itm from an Ottoman defence-work directed against troops landing at Aqaba into an Arab defence-work against reinforcements from the north. It was, Lawrence later explained, to be ‘an extreme example of a turning movement, since it involved a desert journey of 600 miles to capture a trench within gunfire of our ships’.

Of this, Lawrence could tell Cairo nothing: Clayton’s letter had been unequivocal, and he could have been in no doubt that, had he revealed his intentions, he would have received a direct order not to proceed. Therefore: ‘I decided to go my own way, with or without orders.’

The Hijaz war had been an adventure that could be lived like a medieval legend. The Syrian war now beginning was a political betrayal, something a man of Lawrence’s sensibilities could experience only as a psychic crisis. He began to crack at once. ‘Can’t stand another day here,’ he wrote in his diary on 5 June. ‘Will ride north and chuck it.’ In his notebook he clarified his motives for the benefit of his superior: ‘Clayton. I’ve decided to go off alone to Damascus, hoping to get killed on the way. For all sakes, try and clear this show up before it goes further. We are calling them to fight for us on a lie, and I can’t stand it.’

While recruitment continued at Nebk in the Wadi Sirhan, Lawrence embarked on a long, dangerous, far-ranging journey into central Syria. The men around him, caught up in a commotion of movement-building, their comings and goings accompanied by wild shouts and fusillades, now appeared as if characters from a Greek tragedy, blind to their fate, hapless and naive on the way to their doom. Guilt-laden, his mind incapable of rest in the cacophony of the Howeitat encampment, his confusion compounded by his anomalous position as a British officer acting in defiance of orders, imperial interest and conventional military thinking, he slunk away.

Related: How War Pigeons Changed the Course of Battle–and History

Lawrence covered more than 300 miles in just under two weeks. The escape was a tonic. However confused and self-destructive his mood when setting out, he turned the journey to good account. It was partly a reconnaissance, a chance to refresh his knowledge of a landscape he knew, but to see it in a new way, through the eyes of the guerrilla leader he had become. The journey was a small-scale diversionary raid. Recruiting a small group of tribesmen, he dynamited a railway bridge 50 miles north of Damascus and stirred up a general security panic in the Baalbek region – thereby diverting Ottoman attention from Aqaba. On the way back, he made contact with the Arab underground and anti-Ottoman tribal leaders, including Nuri al-Shaalan, the great Ruwalla autocrat of the eastern deserts, whom Lawrence found:

very old; livid, and worn, with a grey sorrow and remorse upon him, and a bitter smile the only mobility in his face. Upon his coarse eyelashes, the eyelids sagged down in tired folds, through which, from the overhead sun, a red light glittered into his eye sockets and made them look like fiery pits in which the man was slowly burning.

The meeting took place at Azrak, an oasis settlement with a Roman fort of black basalt that once blocked the north-western egress of desert raiders coming down the Wadi Sirhan. The old man rekindled Lawrence’s inner anguish by brandishing documents and demanding to know which of Britain’s contradictory promises were to be believed. Upon Lawrence’s answer might depend the hope of winning the Ruwalla when the rebellion rolled northwards. ‘The abyss opened before me suddenly … In the Hijaz, the sherifs were everything, and ourselves accessory; but in this distant north, the repute of Mecca was low, and that of England very great. Our importance grew; our words were more weighty; indeed, a year later, I was almost the chief crook of our gang.’

This post is sponsored by Open Road Media. Thank you for supporting our partners, who make it possible for The Archive to continue publishing the history stories you love.

Featured photo: Wikimedia Commons

.jpg?w=3840)