The American Civl War lasted from 1861 to 1865, dividing the nation between the loyal northerners of the Union and the rebel southerners of the Confederates. We all know that tensions came to a head after Abraham Lincoln won the presidential election on an anti-slavery platform, leading to 11 states seceding from the Union. Many are also familiar with the large-scale destruction wrought on America from the fighting, as well as the roles major players Confederate General Robert E. Lee and Union General Ulysses S. Grant played in the confrontation. However, there are several key strategies, battles, and moves that many overlook in regards to the Civil War.

Related: 10 Civil War Battles That Shaped America's Bloodiest Conflict

While many feel that the Union victory in the war was ultimately inevitable based on division of resources, not all of the Union's maneuvers were stacked so heavily in their favor. In 1863, the Civil War had hit its mid-point. Vicksburg, Mississippi was a major Confederate stronghold along the Mississippi river. Following Lee's botched invasion of Gettysburg in July, the surrender of Vicksburg was the second major blow to the rebels that year. But the road to success was not an easy one, and can be attributed, at least in part, to the incredible efforts of Grierson's Raid in the Spring of 1863.

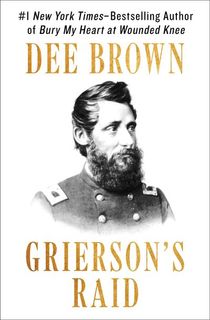

As detailed in Grierson's Raid by celebrated nonfiction author Dee Brown, April 17th, 1863 was the first day of what would become a two-week raid from Tennessee to Louisiana. Led by Colonel Benjamin Grierson, 1,700 Union cavalry troopers advanced on the southern territory to draw the attention of Confederate forces away from General Grant's impending approach across the Mississippi River. But Grierson had been a music teacher before the war—this, paired with his deep distaste for horses, left him an unlikely hero.

Related: 19 Essential Civil War Books

However, Grierson's Raid was the site of a sly and brilliant tactic which found success as shocking as it was hard-fought. As the cavalry men disrupted railway tracks, decimated storehouses, took prisoners, and liberated slaves, Grierson only lost three men to this expedition. Of course, Grierson only made the maneuver look easy in hindsight.

In an excerpt of his vividly detailed definitive work, Dee Brown goes into how Grierson laid the groundwork for the Siege of Vicksburg against seemingly impossible odds.

Read an excerpt from Grierson's Raid below, then download the book.

COLONEL GRIERSON’S SWIFTLY MOVING brigade of cavalry riding southward into eastern Mississippi was not the only diversionary force being used by General Grant in the springtime preparations for what he hoped would be the final assault on Vicksburg. By the time Grierson’s raiders reached New Albany on the 18th, four other movements were well under way. From Memphis, three infantry regiments, a battery of artillery, and two hundred cavalrymen were marching south toward General James Chalmers’ stronghold at Panola. From La Grange, General William Sooy Smith was moving 1,500 infantrymen by rail to Coldwater, with orders to engage Chalmers’ flank along the lower Tallahatchie. From Corinth, 5,000 infantrymen were marching east along the Tennessee River toward Tuscumbia. And from far up in Tennessee, Colonel Abel Streight was bringing a mounted brigade down for a raid into eastern Alabama.

With these five long-planned and well-synchronized movements, Grant and his generals hoped not only to distract the Confederates’ attention from activities around Vicksburg but also to force them to withdraw some reserve troops from the Vicksburg-Jackson defense area. Grant was counting on the two cavalry raids to break the lines of transport for enemy troops and material, leaving the Confederates’ commanding general, John C. Pemberton, temporarily isolated from the remainder of the South.

Related: 9 Best Civil War Movies

It was evident from the orders issued by Grant during the winter that he considered Grierson’s raid as the main thrust, the feint with the punch. From his disastrous past experiences in Chalmers’ well-defended area below Memphis, the general must have known that the small forces he was sending there could do little more than keep the Confederates tied down. General Sooy Smith’s flanking expedition served only as a smokescreen to the right of Grierson’s cavalry. The expedition from Corinth was designed as a similar diversion on the left of Grierson’s drive. As for Streight’s raid into Alabama, it was calculated to keep General Bedford Forrest’s fast-riding rebels occupied far to the east, and might also do some damage to the railroads supplying Vicksburg with troops and ammunition. Streight’s raiders, however, were rated second in priority to Grierson’s men, being mounted mainly on mules and cast-off horses.

Grierson’s cavalrymen had drawn the best horses available—captured Mississippi blood stock and animals collected by the remount station in St. Louis. During the fall and winter, representatives of the quartermaster had searched throughout the western half of the Union, posting notices on the streets of every town and in the local newspapers requisitioning horses “to be not less than fifteen hands high, between five and nine years of age, of dark colors, well broken to the saddle, compactly built, and free from all defects. No mares will be received.”

During breakfast with his staff, Grierson quickly fitted his strategy to the weather. He was fairly confident that no strong Confederate forces were yet massed on either his left or right, and he decided to put his men into a series of diverse movements designed to confuse the enemy as to his real intentions. “I sent a detachment eastward to communicate with Colonel Hatch,” he said in his report, “and make a demonstration toward Chesterville, where a regiment of cavalry was organizing. I also sent an expedition to New Albany, and another northwest toward King’s Bridge, to attack and destroy a portion of a regiment of cavalry organizing there under Major [Alexander H.] Chalmers. I thus sought to create the impression that the object of our advance was to break up these parties.”

Related: Ulysses S. Grant: The Man Who Secured the Union’s Victory in the Civil War

The three detachments sent out by Grierson were drawn from the Seventh Illinois. Colonel Prince selected Captain George W. Trafton, commanding G Company, to lead the raid back into New Albany, and shortly after six o’clock the men were riding north. Trafton also had a second company under his command, but the records do not give its identity.

As they moved slowly back over the five miles into New Albany, a driving rain pelted into their faces, soaked around the collar openings of the ponchos, gradually saturating their blouses and shirts. The hooves of their floundering horses splattered them with daubs of adhesive, orange-colored mud.

During the night a small force of Mississippi state troops had collected in New Albany, and when they sighted Trafton’s two companies more than a hundred rebels moved out to give battle. Some of the Confederates were unmounted. Trafton charged, his men firing and then drawing sabers, driving the state troops back through the town and inflicting several casualties.

Want to keep reading? Download Grierson's Raid.

After Vicksburg surrendered to the Union on July 4th 1863, the Civil War would continue for close to two more years. But this Union victory granted the north control of the Mississippi River—control which was complete after the subsequent surrender of Port Hudson. This control split the Confederacy in two, cutting them off at the knees.

This post is sponsored by Open Road Media. Thank you for supporting our partners, who make it possible for The Archive to continue publishing the history stories you love.