As long as war has existed there have been great commanders. By talent, determination, ruthlessness and luck, their careers changed both the course of military history and history itself. Some are well-remembered, while others are less familiar to the casual reader, yet will be instantly recognizable to military historians and enthusiasts. Regardless of their perceived fame or reputation, these leaders' impact on modern warfare is beyond doubt.

Tokugawa Ieyasu

After centuries of in-fighting known as Sengoku Jidai (the "Warring States" period), Tokugawa Ieyasu emerged as Japan’s shogun. Beginning with the Onin War of the 1460s, rival warlords (daimyo) had schemed and fought almost constantly to unify feudal Japan under one leader, seemingly with no end in sight. Only Oda Nobunaga and Toyotomi Hideoshi had even begun to bring order to the perpetual chaos. Over time Tokugawa Ieyasu also showed his abilities, founding the Tokugawa Shogunate in 1603 after winning the Battle of Sekigahara three years earlier.

Related: Yasuke, the African Samurai

Victory at Osaka Castle in 1617 finally ended Sengoku Jidai and any serious challenge to Tokugawa’s position. Tokugawa’s bahukan system of government also kept samurai and daimyo from starting another Sengoku Jidai thereafter. The Tokugawa Shogunate ruled until the 19th century. The Meiji Restoration of 1868 brought steadily-increasing Western involvement in Japan and steadily-declining Samurai power and influence.

Ulysses Grant

Ulysses Grant had a much more difficult route to greatness. Eventually commanding the Union Army during the American Civil War, Grant had left the army after the Mexican-American War and failed in various business ventures before re-enlisting. Considered a failure and drunkard during his first military career, Grant’s performance at Shiloh in 1862 saw him promoted.

Related: Ulysses S. Grant: The Man Who Secured the Union’s Victory in the Civil War

Grant increasingly dominated the Western theatre. Capturing Vicksburg and Fort Donelson brought control over the Mississippi River, effectively cutting the Confederacy in two. Coupled with the Union naval blockade and European nations refusing to recognize the Confederacy, Grant’s control of the Mississippi steadily strangled transportation and caused supplies to dwindle, hastening Confederate defeat.

Grant had been the latest of many commanders appointed by President Lincoln, many achieving little before resignation or dismissal. Grant’s skill, calmness and determination earned much-needed battlefield victories while other generals foundered.

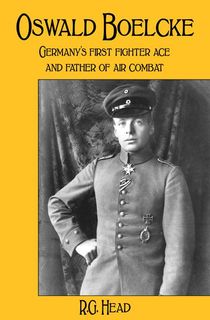

Oswald Boelcke

Oswald Boelcke joined the German Army in 1911 and learned to fly in 1914. Like many pioneer aces his career was brief, but spectacular. Boelcke became known as the father of air combat before dying in an aerial collision with squadron-mate Erwin Bohme in October 1916, achieving more in two years than most pilots ever will.

Boelcke scored 40 kills, earning him Imperial Germany’s highest award, the legendary Blue Max. He also established Jagdstaffel 2, a unit of hand-picked fighter pilots he trained in his personal air combat doctrine called the Dicta Boelcke. Jagdstaffel 2 included many aces including Manfred von Richthofen, the Red Baron. Among other hand-picked aces were later Luftwaffe commanders Ernst Udet and Hermann Goering.

Related: Take a Fresh Look at WWI with 8 Rarely Seen Photos of The Great War

Published in 1916, the Dicta Boelcke was the very first air combat manual, and present-day manuals are still influenced by it. It has long outlasted the war and all its participants, including Boelcke, who died aged only 25. Bohme himself was so distressed by the accident that he had inadvertently caused that he wrecked his own plane upon landing, and was haunted with guilt for the rest of his life.

Abd El-Krim

Abd El-Krim is less familiar to most Western readers, though remembered bitterly by the French and Spanish. A Moroccan guerrilla leader, El-Krim united the tribes of the Rif Mountains against their colonial occupiers. Given tribal and clan rivalries in the region, Krim’s uniting them under one cause was an immense achievement. Beginning in 1920, his war cost thousands of colonist lives, including many members of the legendary French Foreign Legion.

Between 1921 and 1926, France and Spain launched a combined operation to defeat or kill El-Krim. Naval, ground and air forces were deployed and Franco-Spanish forces even resorted to chemical weapons that had been banned after WWI. El-Krim’s tactics included military tunnelling, later successfully adopted by Ho Chi Minh against the French and Americans. Krim’s rebellion cost the French and Spanish some 15-20,000 casualties combined. The colonial powers were also embarrassed on the international stage. Their modern military forces took years to defeat what the European public saw as just a coalition of ill-supplied mountain bandits.

Alberto Bayo, later Che Guevara’s chief instructor, served with El-Krim for several years. It is even claimed that Guevara met El-Krim in 1959. Finally forced to surrender in 1926, El-Krim went into exile on Reunion Island and then in Egypt. Although defeated in the 1920s, El-Krim still lived to see European colonialism ended in North Africa. He died in Cairo in 1963 shortly after French colonists finally left the newly-independent Algeria.

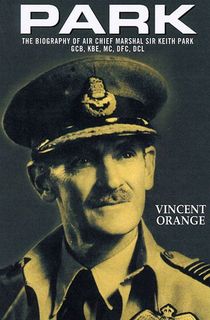

Keith Park

New Zealander Keith Park served at Gallipoli before joining the Royal Flying Corps, becoming an ace in his own right. He remained in the RFC after it became the Royal Air Force and in 1940 commanded 11 Group defending Southern England and London. While Hugh Dowding commanded RAF Fighter Command, 11 Group bore the brunt of the Battle of Britain.

Park’s task was enormous. Facing huge bombing raids daily, Park and 11 Group were stretched to their absolute limits. If the Luftwaffe gained air superiority, England itself was open to invasion. Park’s leadership would decide everything. On September 15, 1940, Winston Churchill himself asked Park what reserves were left. On what later became Battle of Britain Day, there were none. Park had committed every available fighter squadron.

Park was beloved by his airmen who nicknamed him Skipper. Civilians called him the Defender of London. He travelled extensively in his personal Hurricane fighter, visiting airfields to boost morale and always responded quickly to complaints and requests. Park’s hands-on approach made him a popular commander, someone his men wanted to fight for.

Arthur Tedder, Chief of the Air Staff, later said of Park: "If any one man won the Battle of Britain, he did. I do not believe it is realised how much that one man, with his leadership, his calm judgement and his skill, did to save, not only this country, but the world."