By the official start of the Vietnam War, the United States had long been engaged in an attempt to restrain the spread of communism. Although the Battle of Ia Drang was the first major physical conflict between the U.S. and the People’s Army of Vietnam, it was the culmination of years of U.S. aid to South Vietnamese forces.

Hoping to stop communism’s spread, the United States entered the Vietnam War in March 1965. 3,500 US Marines came ashore at Da Nang to aid South Vietnam in their fight against North Vietnam. Their first real fight on the ground didn’t take place until November 14, 1965, when the US Army engaged in battle with the North Vietnam Army (NVA) in the Ia Drang Valley. Notable as one of the first instances in which large-scale helicopters were used for air assault, as well as B-52 strategic bombers, the battle marks a bloody initial conflict between the troops in which both sides claimed victory—a sign of what was to come as the Vietnam War progressed.

Related: 9 Fascinating Vietnam War Books

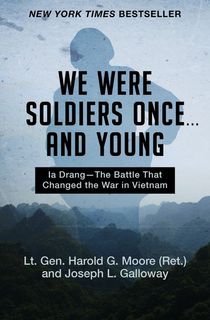

One of the most well-known accounts of the Vietnam War centers on the Battle of Ia Drang. We Were Soldiers Once…and Young was co-written by Lieutenant General Harold (Hal) Moore and war correspondent Joseph L. Galloway, who were both present at the battle. In fact, Galloway was the only journalist on the ground throughout the fighting. However, the two men didn’t just rely on their own perspectives; they also interviewed hundreds of men who fought in the battle, including North Vietnamese commanders. The result is a New York Times bestseller that remains the most authoritative and moving account of the conflict to date.

We Were Soldiers Once…and Young catapulted Galloway into national recognition. He had rescued wounded soldiers from enemy fire during the battle, for which he was awarded a Bronze Star Medal in 1998. This made him the only civilian awarded a medal of valor by the U.S. Army for actions in combat during the Vietnam War. Galloway would go on to have a highly respected career as a war correspondent. He served four tours in Vietnam and reported from the front lines of the Gulf War before covering the Bush administration’s War on Terror and military and political intervention in Iraq. In 2002, We Were Soldiers Once…and Young was adapted into a film starring Barry Pepper as Galloway and Mel Gibson as Moore.

Related: A Previously Untold Account of the Vietnam War

Joseph L. Galloway died on August 18, 2021 at the age of 79. He’s remembered fondly for his fierce patriotism, journalistic integrity, and commitment to unearthing the truth about our military’s overseas activity.

Discover Galloway and Moore’s iconic rendering of the Battle of Ia Drang in the below excerpt from their unforgettable book, We Were Soldiers Once…and Young.

Read on for an excerpt from We Were Soldiers Once...and Young, and then download the book.

Within minutes Devney’s 1st Platoon, which was leading the assault, was attacked heavily by thirty to forty North Vietnamese in khaki uniforms, wearing pith helmets and firing automatic weapons. It was now near 1:00 P.M.; Devney’s men were under attack on both flanks, and they were in trouble. The North Vietnamese were using a well-worn trail as a general axis of advance. Says Sergeant Gilreath: “We were virtually pinned to the ground and taking casualties.” Lieutenant Dennis Deal remembers that moment: “Devney’s platoon was taking moderate fire. We could all hear it through the foliage, and I heard it crackling on my radio. Al was in some sort of trouble. The firing increased in volume and intensity; then I saw my first wounded trooper, probably the first American wounded in LZ X-Ray. He was shot in the neck or mouth or both, was still carrying his rifle, was ambulatory and appeared stunned at what had happened to him. When he asked where to go I put my arm around him and pointed to where I had last seen the battalion commander.”

Here’s what Sergeant Jimmie Jakes of Phenix City, Alabama, who was leading four men in one of Devney’s rifle squads, remembers: “As we were advancing toward the enemy, two of my men and one from another squad were hit by machine-gun fire. I was ordering men to my left and right; some didn’t even belong to our platoon. I yelled to them to lay down a base of fire; then I crawled to aid the wounded. I was able to drag two of the wounded back to our defensive line. We had stopped advancing at this point. As I attempted to drag a third back I was wounded.” An AK-47 round penetrated Jakes’s side and exited through the top of his left shoulder.

Related: The Loach Was One of the Riskiest Helicopter Assignments in Vietnam

Over on the right and slightly behind Al Devney’s men, Lieutenant Henry T. Herrick was maneuvering his 2nd Platoon up the slope toward a meeting with destiny. His company commander, Captain Herren, said: “Herrick’s platoon was probably my most seasoned unit, with outstanding NCOs. They were led by an old pro, SFC [Sergeant First Class] Carl Palmer, who I relied on to counsel and help develop Lieutenant Herrick, much as I did with my other two platoon sergeants—Larry Gilreath of the 1st Platoon and Larry Williams of the 3rd. But the 2nd Platoon had other NCOs who were exceptional: Ernie Savage, a young buck sergeant from Alabama, was a rifle-squad leader; then there was SFC Emanuel (Ranger Mac) McHenry, who was forty years old but could walk the legs off men half his age; Staff Sergeant Paul Hurdle, the weapons-squad leader, who was a Korean War veteran, and Sergeant Ruben Thompson, a fire-team leader with a reputation of never quitting.”

Combat operations at Ia Drang Valley, Vietnam, November 1965. Major Bruce P. Crandall's UH-1D helicopter climbs skyward after discharging a load of infantrymen on a search and destroy mission.

Photo Credit: WikipediaHenry Toro Herrick was red-haired, five foot ten, twenty-four years old, and the son of an astronomy professor at UCLA. He had joined the battalion in July and been given a rifle platoon; he was a hard-charger. When the battalion recon-platoon leader job, a coveted assignment, came open in October, I briefly entertained the notion of giving it to young Herrick. I mentioned Herrick to Sergeant Major Plumley and his response was forceful and swift: “Colonel, if you put Lieutenant Herrick in there he will get them all killed.” We had a gaggle of new second lieutenants in the battalion, and it surprised me that one of them had made such a poor impression on the sergeant major. Herrick, needless to say, did not get the recon-platoon job.

Herrick’s platoon sergeant, Carl Palmer, had voiced his own reservations about the lieutenant to Captain Herren after one of his men was drowned in a river crossing while on patrol. “Sergeant Palmer took me aside after the drowning incident and told me that Herrick would get them all killed with his aggressiveness,” Herren says. “But I couldn’t fault Herrick for that. We were all eager to find the enemy and I figured I could control his impetuous actions.”

Related: 365 Days: Ronald Glasser’s Moving Account of the Vietnam War

Devney reported by radio to Captain Herren that his platoon was pinned down on both flanks. Says Herren: “I directed Lieutenant Herrick to alleviate some of the pressure, ordering him to move up on Devney’s right and gain contact with Devney’s 1st Platoon.” The time was now about 1:15 P.M., and the scrub brush was baking in the ninety-plus-degree heat of midday. A few rounds of enemy 60mm and 82mm mortars and some RPG-2 rocket-propelled grenades were bursting in Devney’s area. Captain Herren and Lieutenant Bill Riddle, his artillery forward observer, now began working the radios, calling in air and artillery fire support.

Devney’s platoon sergeant, Larry Gilreath, was expecting to see Herrick and his men moving up on his right. He did, but not for long. As he moved, Herrick radioed Captain Herren to report that his 2nd Platoon was taking fire from the right, that he had seen a squad of enemy soldiers and was pursuing them. Herren radioed back: “Fine, but be careful; I don’t want you to get pinned down or sucked into anything.”

Gilreath says: “I saw Lieutenant Herrick at a distance of about fifty yards. His weapons squad leader, Sergeant Hurdle, was closest to me. I asked him, ‘Where the hell are you going?’ They were deployed on line and moving fast. I wanted him to stop and set up his two machine guns on my right flank. They kept on moving. I thought they were going to tie in with my men.”

Captain Herren was concerned about Devney’s situation but enthusiastic about Herrick’s contact, which he reported to me by radio. “Shortly after,” Herren says, “I moved out again to catch up with Devney. He reported he was under heavy fire and pinned down. I immediately called Lieutenant Deal to move around to the left and help Devney.”

Dennis Deal had been running the 3rd Platoon, Bravo Company, for only two weeks. “My platoon sergeant was Staff Sergeant Leroy Williams, a true man. He had spent a year and a half in Korea. My weapons-squad leader was Staff Sergeant Wilbur Curry, a full-blooded Seneca Indian from upstate New York, who was in Korea for two years and was reputed to be the best machine gunner in the battalion, if not the division. Just before we left base camp, Curry got too much firewater in him, got a horse from a Vietnamese, and rode it up Route 19 toward Pleiku. Because Colonel Moore knew what a good trooper he really was, he passed on punishing Curry.”

Until now Deal’s platoon had not seen any enemy, but as they moved up fifty yards and approached Devney’s left flank, they came under heavy fire. Sergeant Gilreath remembers seeing the 3rd Platoon “having the same problems we were having with enemy automatic weapons fire. It was coming from a covered machine gun position and it was giving us fits.”

Staff Sergeant William N. Roland, a twenty-two-year-old career soldier who came from Andrews, South Carolina, was one of Deal’s squad leaders. “We began to encounter wounded soldiers from the 1st Platoon. Then we started taking enemy fire, including incoming mortar rounds.” Lieutenant Deal says, “My personal baptism of fire was occurring and I turned around to Sergeant Curry. ‘Chief, I’ve never been shot at before. Is this what it sounds like?’ And he smiled. ‘Yes sir, this is what it sounds like. We are being shot at.’ We had to scream at each other to be heard.”

Related: The 9 Best Vietnam War Movies

The military historian S.L.A. Marshall wrote that, at the beginning of a battle, units fractionalize, groping between the antagonists takes place, and the battle takes form from all this. Marshall had it right. That is precisely what was happening up in the scrub brush above Landing Zone X-Ray this day. And no other single event would have a greater impact on the shape of this battle than what Lieutenant Henry Herrick was in the process of doing. Herrick charged right past Lieutenant Devney’s men, swung his platoon to the right in hot pursuit of a few fleeing enemy soldiers, and disappeared from sight into the brush.

Says Sergeant Ernie Savage of Herrick’s orders: “He made a bad decision, and we knew at the time it was a bad decision. We were breaking contact with the rest of the company. We were supposed to come up on the flank of the 1st Platoon; in fact we were moving away from them. We lost contact with everybody.”

Want to keep reading? Download We Were Soldiers Once...and Young now.

The Vietnam War raged on from 1955 through 1975. Although the first U.S. military action at Ia Drang occurred in 1965, some 10 years of conflict had been supported by U.S. aid prior to the landing of U.S. combat troops. An extension of the Cold War, the United States believed that the fall of any state to communism would lead to a domino effect across Asia, Europe, and eventually the rest of the modern world. Over a million lives would be lost over the 20 years of guerilla and all-out war in Vietnam and Cambodia. Additionally, over 1,000 U.S. service members remain missing in action to this day. Despite American efforts, Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia all transitioned to communist governments in 1975.

This post is sponsored by Open Road Media. Thank you for supporting our partners, who make it possible for The Archive to continue publishing the history stories you love.

Featured photo of 1st Battalion, 7th Cavalry troopers landing at LZ X-Ray: Wikipedia