The oldest of three boys born to the Bulger family, James Joseph “Whitey” Bulger was born on September 3rd, 1929. He was raised a “Southie”, a resident of South Boston, where he would live for most of his life.

While the Bulger boys were exposed to poverty at a young age, William and John excelled in school and were not drawn down the same criminal path as their older brother. James became involved in petty crimes at a young age, leading the local police to become familiar with him. They even gave him his notorious nickname, “Whitey”, for his fair skin and blonde hair. Bulger never liked the nickname, preferring to be called Jim or Jimmy.

Bulger’s first arrest was in 1943, at the age of 14. It would be the first of many arrests in his life. In 1948, he joined the Air Force as an aircraft mechanic. The regimented lifestyle of the military would prove untenable for him, and he was unable to stay out of trouble while enlisted. Whitey was arrested more than once during his time in the military. He was never convicted of the charges he accrued, and was honorably discharged in 1952.

Bulger returned to Massachusetts after his military service, and he took his place back up in the criminal scene in Boston. In 1956, he was arrested for his part in an armed robbery and truck hijacking. This led to Bulger’s first stint in federal prison, at the Atlanta Penitentiary. While there, Bulger was used as a subject in the CIA’s MK-ULTRA program.

Bulger claimed that he had been offered a reduced sentence in exchange for his time in the program. He and the other participants had been led to believe that the program was meant to help find a cure for schizophrenia.

Related: Boston and Beyond: Massachusetts in the Revolutionary War

In actuality, the MK-ULTRA program was designed to test and research drugs thought to have mind-control properties, such as LSD, in the hopes of learning how to weaken subjects and force confessions through psychological torture and brainwashing. Documents later released by the CIA corroborated the fact that Bulger, as well as the other subjects, had been misled about the purpose of the program.

Bulger was transferred to several other facilities during this time, including Alcatraz. In 1965, his third petition for parole was granted, bringing his nine-year stint behind bars to a close.

When Bulger returned to Boston, he found it in uproar. Two local Irish-American gangs, the Killeens and the Mullens, were at war. The Killeens had been the dominant gang in Southie for the past two decades, but were being muscled out by the Mullens. Bulger began to work for the Killeen gang, starting as a janitor and construction worker, and working his way up to bookmaking, loansharking, and acting as an enforcer for them.

Related: 13 Eye-Opening Books About the Mafia

Bulger is said to have committed his first homicide during this gang war, in a case of mistaken identity. Rather than shooting a member of the Mullen gang, Bulger killed the gang member’s law-abiding brother. When another member of the Killeen gang was murdered in retaliation for the crime, Bulger quickly came around to the fact that he was on the losing side.

He approached the leader of the Winter Hill Gang, Howie Winter, claiming that he could end the Killeen-Mullen conflict—by killing the head of the Killeens. On May 13, 1972, Donald Killeen was shot outside of his home, possibly by Bulger. However, some believe that he was actually murdered by two Mullen enforcers.

1959 mugshot of Bulger at Alcatraz.

Photo Credit: Wikimedia CommonsBulger and the Killeens left Boston, certain that they were next. They met with the Mullens on neutral ground, mediated by Howie Winter. By the end of the meeting, the gangs had called a truce, ended the war, and actually joined forces with Winter as their leader.

This shift in power put Bulger and the Mullens at the top of Boston’s criminal enterprise. The actions that Bulger took in the years that followed would go on to inextricably bind his name with violence.

Bulger developed a relationship with the FBI, likely sometime in 1974. His handler was John Connolly, a fellow Southie resident, and a former schoolmate of Bulger’s. However, Bulger always maintained that he was never an informant for the FBI, and that the agency gave him more information than he ever gave to them.

Bulger worked closely with Patrick “Pat” Nee, the former head of the Mullens, during this period. The two were known throughout Boston for working over loansharks and bookies in the area. But things for Bulger and the Winter Hill Gang were about to shift drastically.

In 1979, Howie Winter and several members of the Winter Hill Gang’s leadership were arrested for fixing horse races. Despite the number of high-ranking gang members arrested on these charges, Whitey Bulger and Stephen Flemmi, an enforcer and a fellow informant, were left out of the indictments. It would later be revealed that Agent Connolly worked to keep Bulger out of the indictments.

With no one left at the top, Bulger and Flemmi took over leadership of the Winter Hill Gang. Kevin Weeks, a fellow mobster, was at the top with them.

The early 1980s found Bulger continuing to run the rackets in Boston with an iron fist. His work included the loansharking and bookmaking that he had run under the Killeens, as well as arms trafficking, truck hijacking, and extortion. His connections to various murders increased during this time.

It was difficult for the authorities to bring any cases against Bulger. He was incredibly careful about how and where he and his inner circle spoke about their plans, never discussing them over the phone or in cars for fear of wiretaps. Bulger was also said to have paid off law enforcement within the Boston Police Department, the Massachusetts State Police, and the FBI. When his relationship with the FBI was later revealed, it would become an ongoing source of controversy.

In April of 1994, a joint task force was launched by the Boston Police, the DEA, and the Massachusetts State Police to look into Bulger’s illegal gambling operations. The FBI was kept out of the loop. There was a concern that its previous involvement with Bulger could jeopardize the operation. The task force was able to get a number of bookies to admit to paying protection money to Bulger, and built a Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organization, or RICO case, against him due to his gang ties.

Despite the fact that the FBI had been kept out of the task force, the news of the incoming indictments reached Connolly. Connolly warned Bulger that arrests would be coming at some point in the Christmas season, so Bulger left Boston on December 23, 1994. Flemmi wasn’t so lucky, and was arrested outside of a Boston restaurant early in 1995.

Whitey Bulger, left, meeting with Kevin Weeks.

Photo Credit: Wikimedia CommonsIn Bulger’s absence, Kevin Weeks replaced Bulger as head of the Winter Hill Gang. He would meet Bulger routinely over the next few years, in various cities around the country. However, Weeks’ tenure as the leader of the Winter Hill Gang wouldn’t last as long as Bulger’s. He would be arrested by the DEA in 1999. Connolly was also indicted in 1999 for giving confidential information to the Winter Hill Gang, as well as taking bribes and lying in official reports.

At this point, Bulger was still on the lam, and had been added to the FBI's Most Wanted list. There wouldn’t be a confirmed sighting of him until 2002, when he was spotted in London. Sightings would crop up over the next decade, but he continued to elude authorities. Bulger and his girlfriend, Catherine Greig, were believed to have been sighted all over the world, including Uruguay, Sicily, and British Columbia.

Related: These Irish American History Books Explore Rich History and Culture

On June 22, 2011, Bulger’s 16-year run from the law ended when he was arrested in Santa Monica, California. At the age of 81, Bulger was charged with murder, as well as conspiracy to commit murder, extortion, narcotics distribution, and money-laundering. When agents searched his apartment, they found over half a million dollars in cash, multiple firearms and knives, and a cache of fake IDs.

Whitey Bulger was arraigned on July 6, 2011. He was hit with 48 federal charges, including 19 counts of murder. In 2013, Bulger was found guilty on 31 counts, including 11 counts of murder. He was sentenced to two life sentences in prison, with an additional five years on top of that. Whitey Bulger was sent back to jail after more than 40 years on the outside.

Just like his first stint in prison, Bulger was transferred to several different facilities. He was ultimately transferred to the West Virginia State Penitentiary. On October 30, 2018, just hours after arriving, he was attacked by other inmates and was found unresponsive in his cell. He was declared dead by the penitentiary’s medical examiner just hours later. At the age of 89, a man who had gained a reputation for violence met an incredibly violent end.

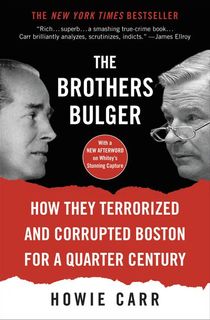

Want to learn more about Whitey Bulger and his politician brother? Download The Brothers Bulger now!

The Brothers Bulger

This latest edition includes a new afterward that details Whitey Bulger's capture.

Sources: The Mob Museum, The Irish Post