After the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941, America joined the Allied Forces in World War II. Though the United States forces were split between European and Pacific theaters of war, the fight against Japan carried far more personal wounds. This is perhaps why the iconic and patriotic image captured by Joe Rosenthal during the raising of the second flag amidst the Battle of Iwo Jima went on to win the Pulitzer Prize and become the symbol of American perseverance.

Related: 21 Essential World War II Books That Examine Every Angle of the Conflict

The Battle of Iwo Jima was a turbulent campaign fought between the United States Marines and the Imperial Army of Japan. Seizing the island of Iwo Jima would give the U.S. access to three airfields ideal for staging an American invasion of mainland Japan. Unbeknownst to American troops, the Japanese had just implemented a new and secret defensive tactic—utilizing the mountainous terrain and dense jungles of the island to camouflage artillery positions.

In preparation for the invasion, the Allies under American leadership unleashed a three-day bombardment upon Iwo Jima. Bombs hailed from the sky in an aerial attack, while ships positioned off the coast rained heavy gunfire onto the island. Unfortunately, the shelling—initially requested to take place over a period three times longer than the handful of days allotted—didn’t have the desired effect. Due to the sharp strategy of Japanese General Tadamichi Kuribayashi, the Japanese forces incurred very little damage from these attempts to weaken them.

On February 19, 1945, U.S. Marines amphibiously landed on Iwo Jima, expecting to undergo a battle no longer than a couple of days. What followed instead was a vicious slog that lasted five weeks. The Battle of Iwo Jima was one of the most brutal and bloody confrontations on the Pacific front.

As American forces first breached the island, they found that steep dunes and soft, ashy landscape made for difficult passage both on foot and with vehicles. And though the Japanese didn’t launch a response as the Marines trudged forward, the delay was merely part of Kuribayashi’s plan.

The Americans were caught off guard, believing that their preliminary bombardment had crippled the local defenses. As the Japanese finally opened fire from their artillery positions amid the mountains, the Marines were halted in their tracks. In the first Japanese sortie, the Marines suffered high casualties.

Related: 18 World War 2 Movies Every History Buff Should Watch

Over several days, roughly 70,000 Marines, among them men like John Basilone, stepped foot on Iwo Jima, outnumbering the Japanese forces there 3-to-1. After fighting for over a month, the Marines sustained an estimated 25,000 American casualties and almost 7,000 deaths. But the Japanese were not without their own significant losses, and an eventual American victory was inevitable.

Even as the long and devastating Battle of Iwo Jima raged on, one key victory was achieved just five days into the conflict. On February 23, a group of Marines managed to make their way to the top of the volcanic Mount Suribachi and raise an American flag, announcing their capture of the mountain. A mere handful of hours later, Marines were sent up the mountain yet again, with a mission to erect a larger flag for better visibility. It was this moment that photographer Joe Rosenthal made legendary through film.

The captured photo is a powerful one, full of artful and dynamic composition. It rises—much like the soldiers—out of the destruction of the battlefield as a symbol of resilience. It speaks to strength, camaraderie, and most importantly of all, triumph. After a devastating attack on American soil pushed the nation to join the war, this image was a reminder that America could and would persist.

Although this image was further immortalized on stamps, posters, and memorials, the sad reality of the situation is that half the men in the picture were killed in action not long after. Those who made it out of Iwo Jima struggled to cope with the war. But these Marines and their sacrifices are certainly not forgotten.

Related: The Best War Books That Enlighten, Move, and Educate Their Readers

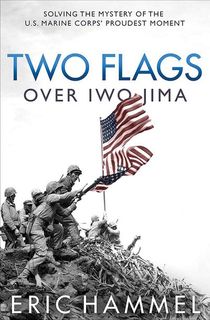

In Two Flags Over Iwo Jima, author Eric Hammel unravels the truth about the historic raising of the flag upon Mount Suribachi. The books dives into the history which has been twisted over time, from the tumultuous battle that led the 28th Marine Regiment to the towering volcano to the often misidentified soldiers who planted their nation’s flag into the soil. Looking at the path from the battle to the aftermath of victory, Hammel pays homage to the heroism and drama of one of the most legendary battles of the Pacific War.

Read an excerpt from Two Flags Over Iwo Jima below, then download the book.

The assault on Suribachi itself jumped off in the pre-dawn hours of D+4: Friday, February 23, 1945. Aerial reconnaissance and photography conducted before, during, and after the invasion landings suggested that there remained, following massive shelling and bombing, only one practical route up the face of the volcano—and so only Lieutenant Colonel Chandler Johnson’s 2nd Battalion, 28th Marines, was designated to step off. The other two battalions scoured their zones for Japanese-manned fighting emplacements they had thus far missed or intentionally bypassed.

The first Marines to test the waters for opposition from the Japanese still holding the summit of the volcano were 15 members of two squads from the 2nd Platoon, Company E, 28th Marines. Private First Class Ira Hayes, an automatic rifleman, describes the brief foray: “It was the morning of [February] 23rd that an order came from [Captain Severance] to send a [15]-man combat patrol clear around the base of Suribachi. Our whole squad was chosen, including [Corporal Harlon] Block, [Sergeant Michael] Strank, [Private First Class Franklin] Sousley, & myself, & another squad also. Well, we set out from our company CP, which was on the east side of Suribachi, & went south to encircle the volcano & wind up of the west side of Suribachi. Thank God we did not encounter any Japs on this patrol. We then returned to our company CP”

Related: 10 Dramatic Battles in American History

The next Marines to move out of the 28th Marines lines—a four-man patrol composed of Company F’s Sergeant Sherman Watson, Private Louis Charlo, Private Theodore White, and Private George Mercer—did so by 0800 hours. The four climbed and hiked—even ran—all the way to the summit, where they encountered an unmanned heavy machine-gun strongpoint at the rim of the crater. Ready ammunition was neatly laid out and the position was shipshape, but no one was home. Overall, a week of intense bombardment on these heights had made a tangle of blasted bunkers, pillboxes, and strewn weapons, gear, and supplies. There was no sign of a living being, so the patrol headed downslope at its best pace. Mission accomplished.

Next, while the four-man Watson patrol was still reconnoitering a route to Suribachi’s summit, Lieutenant Colonel Johnson sent off two three-man patrols, one each from Company D and Company F, to locate other possible routes. And right after that, Johnson asked Company E’s Captain Dave Severance to assemble a patrol of platoon strength with which he planned to send an American flag to the summit.

With his 1st and 2nd platoons otherwise engaged, Severance designated the now-24-man 3rd Platoon of Company E, (down from 45 men on D-day). The patrol leader was, at Colonel Harry Liversedge’s specific request, the Company E executive officer, a 29-year-old mustang (officer commissioned from the ranks), First Lieutenant Harold George Schrier. (Liversedge had worked with fellow former Marine Raider Schrier in the central Solomon Islands.) According to Captain Severance, “[Schrier] was outstanding. He knew what to do and he took a lot of the load off [me].”

Before beginning the climb, which promised to be arduous, Schrier led his men to the 2nd Battalion, 28th Marines, command post for a pep talk from Lieutenant Colonel Johnson. Following the pep talk, as the patrol moved out on its trek into the unknown, Johnson handed a largish folded American flag to George Schrier; the 54-by-48-inch flag had been obtained for Johnson’s battalion weeks earlier in Hawaii by the battalion adjutant, Lieutenant Greeley Wells, from the transport USS Missoula, which had carried the battalion to Saipan for transfer to the LST that had carried it to Iwo Jima.

Schrier stuffed the folded national colors down the front of his utility blouse. As he turned to lead the patrol up the volcano, Johnson said to him, “If you get to the top, put it up.” It was a little after 0800 hours.

During the patrol’s brief stay at the battalion forward command post, located at the base of the volcano’s eastern slope, several hospital corpsmen, litter bearers drawn from a casual (replacement) battalion attached to the 28th Marines, 12 men from the Company E machine-gun section, and at least three Company E 60mm mortar crewmen had been told off from their own units to join the 3rd Platoon patrol, and a Marine combat photographer asked to be attached to the party, bringing the complement to 44, the size of a full-strength infantry platoon in 1945.

Related: 9 Thrilling Military Documentaries on Netflix and More

One more man joined the procession as the patrol passed the Company F command post. The importance of the patrol’s mission required that Lieutenant Schrier be in constant communication with Lieutenant Colonel Johnson, and so the battalion’s portable radio assets had to be rejiggered to provide a radio and a radioman. It fell to Company F to fulfill the need, and the Company F battalion radioman, Private First Class Raymond Jacobs, was selected. According to Jacobs:

“At about the time, while Lieutenant Schrier’s patrol moved toward F Company lines, the word was passed that there was a call for me on the company phone at our [command post]. The phone call was an order from Battalion, telling me that a patrol from E Company would soon be passing through F Company lines. I was to turn on my radio, check in with Battalion, and wait for the E Company patrol. When I saw the patrol, I was to report to the patrol leader and accompany him up Suribachi to provide radio communication between the patrol and Battalion.

When the patrol appeared, I made contact with Lieutenant Schrier and repeated my orders. He told me to fall in and said, ‘Let’s go.’”

Intent on both moving and exercising his step up from platoon sergeant to platoon leader on February 21, 20-year-old Platoon “Sergeant Boots Thomas called out, “Patrol, up the hill. Come on, let’s move out.”

With that, the patrol stepped over the battalion front line—and Captain Dave Severance had a moment of crystal-clear regret. “I thought I was sending them to their deaths. I thought the Japanese were waiting for them.”

Related: 9 Outstanding Audiobooks for Every Kind of History Buff

The success of the stamina-sapping climb to Suribachi’s summit smacks of inevitability now, but at 0800 hours on February 23, 1945, it was a potentially fatal decision to dispatch 45 young men armed with only portable infantry weapons to the steep, shell-blasted side of the volcano when everyone involved knew that the feature was well defended by at least a few hundred well-armed, diehard Japanese troops. There is no explaining the sanguine and sanguinary leap Chandler Johnson was taking with other people’s lives, but Johnson had his orders, and he was willing to issue like orders to his troops, who, following months of training and four days of combat under his fiery brand of leadership, trusted him to do right by them.

Want to keep reading? Download Two Flags Over Iwo Jima.

For the most part, remembrances of Iwo Jima tend to focus on the second raising of the flag. However, the achievements of the men who pioneered the path up Mount Suribachi—as well as the tens of thousands of soldiers who set out on their mission on Iwo Jima—deserve more than to be forgotten amongst history. The wilting memory of the surrounding events of the iconic photograph is a tragedy that deepens when paired with the reality of the invasion’s results.

In the wake of the invasion of Iwo Jima and the high cost of lives sacrificed for success, the true strategic value of the mission became hotly debated. The airfields won in the battle were never used for their original purpose of a staging area for a U.S. attack on the Japanese mainland. After all was said in done, the island was used only as for the emergency landing of USAAF B-29s, once Navy Seabees repaired the landing strips.

The Pacific Theater of WWII came to an end less than six months after the historic flag raising on Iwo Jima. Japan surrendered officially on August 15th, 1945, a few days following the devastating and tragic release of U.S. atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

This post is sponsored by Open Road Integrated Media. Thank you for supporting our partners, who make it possible for The Archive to continue publishing the history stories you love.

Featured photo from the cover of "Two Flags Over Iwo Jima" by Eric Hammel