The 1912 sinking of the RMS Titanic is arguably the most infamous shipwreck to date. Over a century later, its story lives on through films, books, and memorials. The world remains captivated with uncovering the truth behind the ship's unfortunate fate, as well as the stories of the people who were on board.

Built by the Harland and Wolff shipyard in Northern Ireland, the RMS Titanic was the largest passenger liner in service, and it was the second of three Olympic-class ocean liners. On April 10, 1912, the Titanic set out on her maiden voyage from Southampton, England across the Atlantic Ocean to New York City.

Related: 11 Captivating Titanic Books

Four days into the journey, the ship collided with an iceberg. What was initially assumed to be a minor scratch ended up causing the deadliest sinking of an ocean liner to date. Ironically, the ship had advanced safety features for the time, and was deemed “unsinkable” before facing her disastrous end.

Of the estimated 2,224 passengers and crew aboard the Titanic, over 1,500 lives were lost—including the ship's captain, Edward Smith, who adhered to the maritime tradition of going down with the ship. One critical issue was the amount of lifeboats available. The Titanic set sail with only enough tenders to hold a total of 1,178 passengers—leaving about half of the people onboard with no chance of escape.

Historian Walter Lord took a closer look at the maritime disaster in his book, A Night to Remember. Originally published in 1955, this classic book recreates the last night aboard the ship with intimate details from personal accounts and interviews with survivors.

Related: Walter Lord is the Pop Historian All History Lovers Should Read

Lord continued his investigative work in 1976 with The Night Lives On. Combining over 30 years of research with updated insights on some of the most puzzling aspects of the wreck, including the conditions that contributed to its disaster, The Night Lives On provides readers with a deeper look into the sinking of the Titanic.

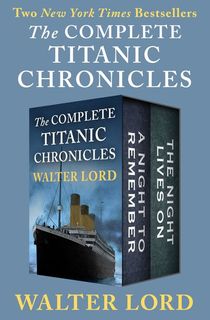

Thorough and well-researched, these books stand the test of time and are as readable today as when they were first published. You can get your hands on both New York Times bestsellers with The Complete Titanic Chronicles. Including both A Night to Remember and The Night Lives On, this book bundle is the definitive account of the passenger liner’s fate.

Read an excerpt from The Night Lives On, then download The Complete Titanic Chronicles.

Not one word about slowing down. Why was this most obvious of all precautions not even mentioned? The usual answer is that Captain Smith thought the Titanic was unsinkable. But even if the ship were unsinkable, the Captain surely didn’t want to hit an iceberg.

Actually, he didn’t slow down because he was sure that on this brilliantly clear night any iceberg could be spotted in time to avoid it. In reaching that decision, Smith did not feel he was doing anything rash. He was following the practice of all captains on the Atlantic run, except for a few slowpokes like James Clayton Barr of the Cunarder Caronia, whose legendary caution at the slightest sign of haze had earned him the derisive nickname “Foggy.”

Knuckling under the competitive pressure of keeping schedule, most captains ran at full steam, despite strong evidence that ice was not as easily sighted as generally claimed. Especially noteworthy was the harrowing ordeal of the Guion Liner Arizona in November 1879. Like the Titanic, she was the largest liner of her day. Eastbound off the Banks of Newfoundland, she raced through a night that was cloudy, but with good visibility. Taking advantage of the calm seas, the passengers gathered in the lounge for a concert.

Suddenly there was a fearful crash, sending everybody sprawling among the palms and violins. The Arizona had smashed head on into a giant iceberg, shattering 30 feet of her bow. But the forward bulkhead held; there were no casualties; and two days later she limped into St. John’s. In a curious twist of logic, the accident was hailed as an example of the safety of ships, rather than the dangers of ice.

Related: 7 Books About Disastrous Shipwrecks in History

There were other close calls too. In 1907 the North German Lloyd Liner Kronprinz Wilhelm dented her bow and scarred her starboard side, brushing a berg in the pre-dawn darkness. In 1909 the immigrant Ship Volturno barely escaped damage, running through a huge ice field. In 1911 the Anchor Liner Columbia struck a berg off Cape Race, driving her bow plates back ten feet. The jar injured several crewmen and broke one passenger’s ankle. It was foggy at the time; so perhaps the accident was discounted.

Such incidents were ignored; most captains continued to run at full speed. Always dangerous, the practice became even more so with the vast leap in the size of ships at the turn of the century. It was one thing to dodge an iceberg in the 10,000-ton Majestic, Captain Smith’s command in 1902, but quite a different matter only ten years later in the 46,000-ton Titanic. The momentum of such a huge ship was enormous, and she just couldn’t stop suddenly or turn on a dime.

The Titanic tested making an emergency stop only once during those brief trials in Belfast Lough, and that at the very moderate speed of 18 knots. Her turning tests seem almost as minimal: she apparently made two complete circles at 18-20 knots and then carried out three other turns at 11, 19½, and 21¼ knots. Her performance at maximum speed remains a mystery.

Captain Edward Smith.

Photo Credit: Wikimedia CommonsOnce again the question arises: how much did Captain Smith really know about the great vessel under his feet?

Arguably, the practice of maintaining speed might have been a practical necessity in the days before wireless, for who knew where the ice really was? The sightings came from vessels reaching port several days later, and by that time the information was too stale to pinpoint the danger. But Signor Marconi’s genius changed everything. The reports reaching the Titanic told exactly where the ice could be found, only hours away.

Why couldn’t Captain Smith and his officers see the difference? Certainly they knew the importance of wireless in an emergency. The help summoned by the sinking liner Republic in 1909 proved that. But no one on the Titanic’s bridge seemed to appreciate the value of wireless as a constant, continuous navigational aid. Basically, they still thought of it as a novelty—something that lay outside the normal running of the ship. It was a mindset tellingly illustrated by the way the wireless operators were carried on the roster of the crew. Phillips and Bride were not listed with the Deck Department; they came under the Victualling Department—like stewards and pastry chefs.

So the Titanic raced on through the starlit night of April 14. At 10 P.M. First Officer Murdoch arrived on the bridge to take over Second Officer Lightoller’s watch. His first words: “It’s pretty cold.”

Related: The Secret Cold War Mission That Helped America Find The Titanic

“Yes, it’s freezing,” answered Lightoller, and he added that the ship might be up around the ice any time now. The temperature was down to 32°, the water an even colder 31°. A warm bunk was clearly the place to be, and Lightoller quickly passed on what else the new watch needed to know: the carpenter and engine room had been told to watch their water, keep it from freezing…the crow’s nest had been warned to keep a sharp lookout for ice, “especially small ice and growlers”…the Captain had left word to be called “if it becomes at all doubtful.”

Lightoller later denied that the sudden cold had any significance. He pointed out that on the North Atlantic the temperature often took a nose dive without any icebergs in the area. Indeed this was true. The sharp drop in temperature did not necessarily mean ice, but it was also true that it could mean ice. It was, in short, one more signal calling for caution. After all, that was the whole point of taking the temperature of the water every two hours.

There’s no evidence that either Lightoller or Murdoch saw it that way. The bitter cold and the reported ice remained two separate problems. Lightoller had passed on all the information he could; so now he went off on his final rounds, while Murdoch pondered the empty night.

A few yards aft along the Boat Deck, First Wireless Operator Phillips dug in to a stack of outgoing messages. His set had a range of only 400 miles during daylight, and the American traffic had piled up. Now at last he was in touch with Cape Race and was working off the backlog. Some were passenger messages for New York—arrival times, requests for hotel reservations, instructions to business associates. Others were being relayed for ships no longer in direct touch with the land.

At 11 P.M. the steamer Californian suddenly broke in: “I say, old man, we’re stopped and surrounded by ice.” She was so close that her signal almost blasted Phillips’s ears off.

“Shut up, shut up,” he shot back, “I’m busy. I’m working Cape Race.” Then he went back to the outgoing pile—messages like this one relayed to a Los Angeles address from a passenger on the Amerika:

NO SEASICKNESS. ALL WELL. NOTIFY ALL INTERESTED. POKER BUSINESS GOOD. AL.

In the crow’s nest Lookouts Fleet and Lee peered into the dark. There was little conversation; they were keeping an extra-sharp lookout. At 11:40 Fleet suddenly spotted something even blacker than the night. He banged the crow’s-nest bell three times and lifted the phone to the bridge. Three words were enough to explain the trouble: “Iceberg right ahead.”

Now it was Murdoch’s problem. He put his helm hard astarboard, hoping to “port around” the ice, and at the same time pulled the engine room telegraph to STOP, and then REVERSE ENGINES. But it was too late: 37 seconds later the Titanic brushed by the berg with that faint, grinding jar that every student of the disaster knows so well.

Related: Lost at Sea: What Happened to the Mary Celeste?

The 37 seconds—based on tests later made with the Olympic—are significant only for what they reveal about human miscalculations. At 22½ knots the Titanic was moving at a rate of 38 feet a second…meaning that the berg had been sighted less than 500 yards away. But all the experts agreed that on a clear night like this the ice should have been seen much farther off. Lightoller thought at least a mile or so, and this undoubtedly reflected Captain Smith’s opinion, for they both had gone over this very point on the bridge shortly after 9:00. The search immediately began for some extenuating circumstance that could explain the difference.

Suspicion focused first on the lookouts. How good were their eyes? Fleet’s had not been tested in five years, and Lee’s not since the Boer War. Yet tests after the collision showed both men had sound vision. Nor were they inexperienced. Unlike most lines, White Star used trained, full-time lookouts, who received extra pay for their work.

Next it was the lookouts’ turn to complain. They charged that there were no binoculars in the crow’s nest. A pair had been supplied during the trip from Belfast to Southampton, but during a last-minute shake-up of personnel they had been removed and never replaced. After hearing numerous experts on the subject, the British Inquiry decided that it really didn’t matter. Binoculars were useful in identifying objects, but not in initially sighting them. That was better done by the naked eye. Here, there was no problem of identification; Fleet knew all too well what he had seen.

The Titanic departs from Southampton on April 10, 1912.

Photo Credit: Wikimedia CommonsThen Lookout Lee came up with a “haze” over the water. He described dramatically how Fleet had said to him, “Well, if we can see through that, we will be lucky.” Fleet denied the conversation and said the haze was “nothing to talk about.” Lightoller, Boxhall, and Quartermaster Hitchens, who had been at the wheel, all described the night as perfectly clear. In the end, the British Inquiry wrote off Lee’s “haze” as an understandable bit of wishful thinking.

Lightoller himself contributed what became known as the “blue berg” theory. He argued that the iceberg had recently capsized and was showing only the dark side that had previously been under water, making it almost invisible. But this theory did not seem to fit the recollections of the few survivors who actually saw the berg. It was anything but invisible to Quartermaster Rowe, standing on the after bridge. He estimated that it was about 100 feet high, and he initially mistook it for a windjammer gliding along the side of the ship with all sails set.

The only explanation left was “fate.” As Lightoller put it, the Titanic was the victim of an extraordinary set of circumstances that could only happen once in a hundred years. Normally there would have been no problem, but on this particularly freakish night “everything was against us.”

Related: The Deadly Collision Between SS Andrea Doria and MS Stockholm

But this explanation implies that Captain Smith didn’t know—and couldn’t be expected to know—the nature of the night he was up against. But he did know. He fully realized that the sea was flat calm, that there was no moon, no wind, no swell. He understood all this and took it into account in deciding not to reduce speed. Under these circumstances the collision quickly loses its supernatural quality and becomes simply a case of miscalculation.

Given the competitive pressures of the North Atlantic run, the chances taken, the lack of experience with ships of such immense size, the haphazard procedures of the wireless room, the casualness of the bridge, and the misassessment of what speed was safe, it’s remarkable that the Titanic steamed for two hours and ten minutes through ice-infested waters without coming to grief any sooner.

“Everything was against us”? The wonder is that she lasted as long as she did.

Want to keep reading? Download The Complete Titanic Chronicles now!

This post is sponsored by Open Road Media. Thank you for supporting our partners, who make it possible for The Archive to continue publishing the history stories you love.