Everyone has heard of the Salem witch trials, as well as the extensive witch trials that took place in Europe during the early modern period. But what was happening to alleged witches around the rest of the world?

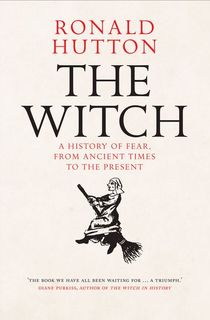

Historian Ronald Hutton seeks to answer that question in his book The Witch. An expert on ancient, medieval, and modern paganism and witchcraft beliefs, Hutton uses his knowledge to shed light on the treatment of accused witches and the beliefs held about witchcraft in Africa, the Middle East, South Asia, Australia, and the Americas ranging from ancient to modern times.

Broadening the conversation about witches from a Eurocentric perspective to a global one, Hutton explores how witchcraft came to mean one thing in one place and something totally different in another, and whether there are common threads between cultures and their perception of black magic.

Read a passage from The Witch below, then download the book!

There is little doubt that in every inhabited continent of the world, the majority of recorded human societies have believed in, and feared, an ability by some individuals to cause misfortune and injury to others by non-physical and uncanny (‘magical’) means: this has been the single most striking lesson of anthropological fieldwork and the writing of extra-European history. One prominent historian of early modern Europe, Robin Briggs, has in fact proposed that a fear of witchcraft might be inherent in humanity: ‘a psychic potential we cannot help carrying around within ourselves as part of our long-term inheritance’. Speaking from anthropology, Peter Geschiere proposed that ‘notions, now translated throughout Africa as “witchcraft”, reflect a struggle with problems common to all human societies’. What is valuable about these insights is that they testify to the general truth that human beings traditionally have great trouble in coping with the concept of random chance. People tend on the whole to want to assign occurrences of remarkable good or bad luck to agency, either human or superhuman. It is important to emphasize, however, that malevolent humans have been only one kind of agent to whom such causation has been attributed: the others include deities, non-human spirits that inhabit the terrestrial world, or the spirits of dead human ancestors. All of these, if offended by the actions of individual people, or if inherently hostile to the human race, could inflict death, sickness or other serious misfortunes. Wherever they appear, these alternative beliefs either limit or exclude a tendency to attribute suffering to witchcraft.

In addition, many societies have believed that certain humans have the power to blight others without intention to do so, and often without knowledge of having done so. This is achieved by unwittingly investing a form of words or a look with destructive power: in the case of malign sight, this trait has become generally known to English-speakers as ‘the evil eye’. Belief in it tends to have a dampening effect on a fear of witches wherever it is found, which is mainly in most of the Middle East and North Africa, from Morocco to Iran, with outliers in parts of Europe and India. This is because it is thought to be part of the possessing person’s organic constitution. As such, it is wholly compatible with witchcraft if the person concerned triggers it consciously and deliberately to do harm, as some are thought to do across its range. A majority of those who embody this malign power, however, are believed to do so wholly innately and involuntarily, so that they cannot in justice be held personally responsible for its effects. Protection and remedies for it mainly take the form of counter-magic, including the wearing of amulets, charms and talismans, the reciting of prayers and incantations, the making of sacrifices and pilgrimages and carrying out of exorcisms, and the avoidance or placation of the person who is locally presumed to possess it. Across the range in which it is an important component of belief, it is used to explain precisely the sort of uncanny misfortunes that are blamed elsewhere on witchcraft.

Alternative explanations for misfortune that rule out or marginalize witchcraft are found across most of the world. Before modern times, the largest witch-free area on the planet was probably Siberia, which spans a third of the northern hemisphere; a consideration of it will play a major part in Chapter Three of this book. Elsewhere in the world, societies that do not believe in witchcraft, or do not believe that it should be taken very seriously, are seldom found in compact concentrations but scattered between peoples who fear witches intensely. Although rarer than groups with a significant fear of witchcraft, they are present in most continents: the Andaman Islanders of the Indian Ocean, the Korongo of the Sudan, the Tallensi of northern Ghana, the Gurage of Ethiopia, the Mbuti of the Congo basin, the Fijians of the Pacific, the hill tribes of Uttar Pradesh, the Slave and Sekani Indians of north-west Canada, and the Ngaing, Mae Enga, Manus and Daribi of New Guinea are all examples. The Ndembu, in Zambia, attributed misfortune to angry ancestral spirits, but the latter were seen as aroused by malevolent humans, in effect making the spirits the agents of witches. However, it was the spirits who were propitiated, by ritual, and so the witches rendered harmless and ignored.

'The Magic Circle' by John William Waterhouse, 1886.

Photo Credit: WikipediaAmong peoples who do have a concept of witchcraft, the intensity with which it is feared can vary greatly, even within the same region or state. Among the ethnic groups contained within the modern state of Cameroon are the Banyang, the Bamileke and the Bakweri. The first of those believed in witches but very rarely accused anybody of being one. Those afflicted by hostile magic were believed to have brought their misfortune on themselves. The second took witchcraft seriously and made great efforts to detect its practitioners. The latter, however, were not held responsible for their actions, and were thought to lose their powers automatically on being publically exposed. The third people feared witchcraft intensely, hunted down its presumed operators, and believed that they remained dangerous and malevolent even when identified, so that they needed to be punished directly in proportion to the harm they were thought to have caused. In neighbouring Nigeria, a clutch of tribal societies shared very similar theoretical beliefs about the existence of witches, but in practice the Ekoi dreaded them, the Ibibio and Ijo feared them moderately, and the Ibo and Yakö took little notice of them.

Likewise, a survey made in 1985 of a sample of well-studied peoples in the Melanesian archipelago found that two of them did not believe that humans used malevolent magic; five thought it a legitimate monopoly of hereditary leaders and used by them productively in order to keep order and conduct warfare; twenty-three believed that such leaders could use it but it was not respectable of them to do so; five conceived of it as a covert weapon of the oppressed, employed against unpopular leaders; eleven identified it as a means by which ordinary members of the community secretly harmed each other, but generally managed in practice to contain the tensions provoked by fears of it; and six had the same belief but were badly disrupted by the suspicions that resulted. Among a single people, the intensity with which witchcraft was feared could vary according to the kind of settlement in which people lived. The Maya of the Yucatan Peninsula of Mexico all hated witches equally in theory during the early twentieth century, but those in villages were rarely inclined to suspect anybody of being one, while the tension was much greater in towns: in the district capital of Dzitas during the 1930s, 10 percent of the adult population were thought to have been either perpetrators or victims of witchcraft.

The identification of a belief in witchcraft among extra-European peoples, by a European scholar, may often involve the extraction of one element from a range of native concepts of magic and of kinds of magician. The Wimbum of north-west Cameroon used three terms for occult knowledge: bfiu, the harmless employment of arcane powers for self-protection; brii, occult power malevolently used, but sometimes merely as a prank; and tfu, an inborn magical force operated under cover of darkness which could be used for both good and evil ends. Witchcraft in the European sense could embrace some forms of both brii and tfu, but the Wimbum also believed in a special strain of the latter, tfu yibi, which consisted of killing other humans magically in order to eat their flesh, and those who deployed that would correspond precisely to the early modern European witch figure. The Nalumin of the mountains of south-eastern New Guinea distinguished biis from yakop. The former were people, mostly female, who killed others in uncanny ways, using invisible weapons while roaming in spirit-body, in order to eat the flesh of their victims in communal feasts. The latter was a technique, used mainly by women, which consisted of killing by burying personal leavings of the intended victim – food scraps, nail clippings and hair – with spells. The two methods, however, were believed to be combined at times by the same individual, and anybody thought to use either would correspond to the European figure of the witch; which is, indeed, how the anthropologist making the study interpreted them.

A final example of such equivalence is supplied by the Tlaxcala province of central Mexico, where the rural natives have feared tetlachiwike, people of both sexes who harmed by a touch or glance (the local equivalent to the evil eye or touch); tlawelpochime, people, mostly women, who sucked the blood of infants and so killed them, and caused harm to humans and their crops or livestock; tetzitazcs, men who could bring rain or hail; tetlachihuics, magicians who were believed to have powers which could be used for good or harm; and the nahuatl, a person of either sex who changed into animal shape to work harm or play tricks. The tetlachihuics were generally respected, and much employed for healing and other magical services, though sometimes murdered if they were thought to have used their abilities to kill: here as elsewhere in this book, the term ‘murder’ is used in its precise legal sense of unofficial and unsanctioned homicide. The shape-shifting nahuatl was believed to employ her or his powers of transformation to steal or rape as well as to inflict practical jokes, but did not inspire the fear and hatred that was accorded the child-murdering tlawelpochime. It was the latter to which Spanish-speaking natives gave the term bruja or brujo, meaning ‘witch’, and was regarded as inherently evil and associated with the Christian Devil. Wim van Binsbergen, commenting on the complexities of belief in magic among Africans in 2001, could still conclude with regard to witchcraft that ‘the amazing point is not so much variation across the African continent, but convergence’. Adam Ashforth, considering attitudes to destructive magic and its alleged perpetrators in the modern Soweto township near Johannesburg, decided that he had to use the terms ‘witchcraft’ and ‘witch’ because ‘there is no avoiding them’.

Want to keep reading? Download The Witch today!

This post is sponsored by Open Road Media. Thank you for supporting our partners, who make it possible for The Archive to continue publishing the history stories you love.