Between 1950 and 1970, the Vatican conspired with the American Catholic Church to send over four thousand Italian children to “good” Catholic homes in the United States. In most cases, these children were not orphans, as their adoptive parents thought, but the so-called illegitimate children of single mothers who could not support them or were pressured by family and clergy into giving them away.

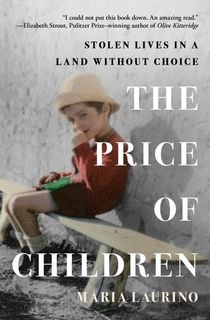

In her new book, The Price of Children, Italian-American journalist Maria Laurino dives into the hidden adoption scandal that permanently separated thousands of unwitting Italian mothers from their children.

Drawing from archival correspondence among priests who ran the program and interviews with birth mothers and their adopted children, Laurino expertly combines narrative and research to build a case in which the facts are as compelling as the underlying emotions. She handles her subjects delicately but tackles the Vatican head-on, laying bare the extent to which the Church played a role in not only the program itself, but the religious cultural milieu that fed it.

What started as a post-war program spearheaded by the U.S. to relocate children displaced and orphaned by World War II evolved into a mechanism of Pope Pius XII’s plan to see the Church reclaim its power in a nation where faith had been dulled by war and, as the Pope would argue, communism.

At the center of the plot to rid Italy of “illegitimate” children and reassert Catholic values of chastity and purity as pillars of Italian womanhood was a dubious consent form that severed all rights of a mother to her child. These shadow forms existed parallel to a more transparent form approved by an acquiescent Italian government.

Pope Pius XII.

Photo Credit: True Restoration / FlickrIn many cases, lawyers or doctors signed these forms without the mother’s consent. In those cases where the mother herself signed the form, her material circumstances, as well as intense religious stigma, often pressured her to do so, and her education level often barred her from understanding the extent of what she was signing.

In this manner, thousands of mothers entrusted their children to the Church’s homes for illegitimate children, only to return and find them vanished, with no way of ever contacting them again. In some instances, such as the case at the center of Laurino’s extensive investigation, the mother’s name was wiped from the birth certificate altogether. In others, mothers were falsely told their babies had died.

The Church, of course, profited handsomely from this program, not only in terms of cultural currency but monetarily.

For a sneak peek at The Price of Children, read the excerpted passages below, then download the book today to read this moving masterpiece of investigative journalism in full.

When I became a mother, our baby boy only five months old, my husband was invited to teach in Milan. I found it appealing to push a pram in a country that still retains the popular image of mamma e bambini, the pronouncement of a fierce maternal love and attachment that seemed more powerful than anywhere else I knew. When our son was four years old and we were vacationing in Rome, I could envision no culture more charming than one whose people stretched kneaded dough into the shape of a heart and delivered the reimagined pizza onto my child’s plate. But my alluring ideas about the land of mamma e bambini had been formed without historical knowledge, my failure to understand that such maternal love had been denied through the centuries to countless women considered unfit.

I didn’t know, in fact, that the system of anonymous infant abandonment originated in Italy in the thirteenth century and flourished in the following centuries, as unwed mothers placed their illegitimate babies into an abandonment wheel, a practice that spread to most of Catholic Europe and Russia. I didn’t know that in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries the Church used its populace to spy on the bedroom behavior of couples, like an ancient prototype of the Stasi except focused solely on the Church’s primary enterprise, sex, insisting that midwives report to parish priests all out-of-wedlock births. I didn’t know that hundreds of thousands of infants perished in these disease-ridden institutions, or that the Church held the horrifying logic that babies baptized inside would be protected in heaven, a far better fate than being raised in sin on earth.

Institutions with names like Bologna’s “Hospital of the Little Bastards” marked these children from birth. In Protestant countries, however, the rates of abandonment remained much lower as Anglo-Saxon society looked down upon out-of-wedlock births but believed it was both parents’ responsibility to raise the child they had conceived.

This Roman Catholic Church attitude toward women did not cease in the twentieth century, it just assumed a new form. With commercial airline travel and a clause added to the Displaced Persons Act, the Church could send the “little bastards” to adoptive families in America. The religious and social pressure that forced women to surrender their illegitimate babies echoed the medieval logic of the abandonment wheel.

The beliefs that laid the foundation for the Church’s orphan program can be traced to ancient Italy, but the decision to send large numbers of children to America was also a decidedly modern and political one. To understand more fully what began in postwar Italy and continued into the late 1960s, another shift in vision needs to take place, beyond the room where the mother held the pen and the social worker pointed to the signature line.

A headline for a newspaper photo tucked into a manila file reads, “First Italian War Orphans Arrive in U.S.” The picture, taken before their departure in the summer of 1951, reveals a dour lot of five girls and four boys. The girls, whose ages look to range from three- to ten-years-old, wear patterned dresses with puff sleeves, white anklets, and thick-soled black shoes, along with, oddly to the modern eye, head coverings that resemble a nun’s short veil or a kerchiefed storybook maiden. Their eyes dart from the camera or embrace it as wary supplicants. The boys, ages about three to seven, whose faces express a grim register of pout to scowl, are dressed in white shirts and dark shorts. Pope Pius XII stands in the center of the photo, hands clasped, with the children flanked beside him. Among the people behind the Pope are his niece, Princess Gabriella Pacelli, and Monsignor Landi; both the priest and the Pope’s elegant niece, unveiled, and wearing a dark sweater with a single strand necklace, accompanied this first batch of children on their flight to New York, serving as the program’s earliest ambassadors. Thirty-five other children were issued visas for America that year.

Those nine children legally entered the United States because of an amendment added in 1950 to the Displaced Persons Act of 1948. A report to the American Congress explained the issuance of five thousand new non-quota visas under section 2(f) of the amended Act, which was intended “to provide homes for children who lost one parent or both parents as the result of Nazi and Communist aggression.” The original Displaced Persons Act had defined a “war orphan” as a child under sixteen-years-old who had lost both parents to the conflict. But the revised amendment changed the definition of a war orphan to a child with one parent who was “incapable of providing care” due to the “death or disappearance” of the other parent. The broad definitions both of disappearance, and of the ability to provide care, allowed for much latitude in the years to come.

Those five thousand visas were made available to eighteen European countries, but the majority were wary of sending off children to the United States, especially because families suffering from the devastating losses of war wanted to preserve kinship ties. Yet Italy, land of mamma e bambini, running its program under the auspices of the Catholic Church, eagerly chose to make use of them. The National Catholic Welfare Conference, the leading organizational arm of the American Catholic Church, and the group in charge of the orphan program based in Rome, explained in its 1950 annual report: “A preliminary survey by the War Relief Services personnel abroad would indicate that most of the aforementioned countries are not anxious to have their young citizens emigrate. Therefore, the area of concentration for the most part in relation to these orphans eligible under the bill will be Italy. We feel that many Catholic children will be able to come to the United States to take their places in good Catholic families.”

Throughout the 1950s, the Church lobbied for this amendment—originally intended as a temporary measure—to be extended numerous times by an American Congress. In 1961, the United States made this new definition of orphan permanent, allowing foreign children to enter the country as immigrants to be adopted by American couples without any quota restrictions. This was the legal mechanism that allowed thousands of Italy’s illegitimate children to come to America over those two decades, the route traveled by John Campitelli, his siblings, Paul, David, and Sara, as well as my cousin. The orphan program would remain unchallenged, except for an alarming few months for the Church in the summer of 1959, when a spate of bad publicity about the black marketing of Italian children to America threatened to end what had become by then a highly efficient adoption machine.

The war orphan—which turned into the orphan—program found its particular Italian form in the accumulated effects of the legacy of anonymous abandonment, the ashes wrought by two decades of Fascist rule, and the new political realities that Italy faced. It was an odd confluence of Cold War politics and ancient religious beliefs about women, sex, and sin, intertwined in the aftermath of World War II. To use a twenty-first century image to analogize what transpired in the mid-twentieth century, when the personal and political had become fatefully interlocked, a national emergency (in Pope Pius XII’s deeply ascetic eyes) had befallen Italy with enemies poised not only at its borders, but already penetrated within. The Pope’s response to these myriad dangers was both quick and concrete: The Church needed to build a wall of chastity.

And who would end up paying for it? Women, of course.

To keep reading, download The Price of Children today.

This post is sponsored by Open Road Media. Thank you for supporting our partners, who make it possible for The Archive to continue publishing the history stories you love.