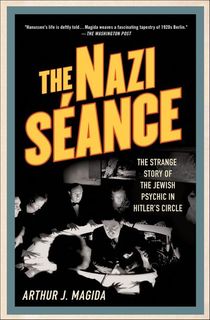

When World War I ended, Germany was in shambles. Quickly, fraudsters and troublemakers seized on the aftermath, offering various occult remedies, including seances, readings, and even communions with the deceased.

People wanted an escape from the realities of violence and cruelty experienced throughout the war—and continuing to permeate all facets of life. More sought after than any other clairvoyant in the 1930s Berlin was Erik Jan Hanussen, a Jewish mind reader originally from Vienna. He would go on to provide services for high-ranking Nazis and Storm Troops, and even, at one point, Hitler himself.

Believing he could befriend and manipulate some of the most powerful figures of the 20th century, just as he had done with his fans, Hanussen laid his traps. Predicting the rise of the Nazi Party, he swiftly transformed his occult newspaper into Nazi propaganda, garnering the attention and support of Hitler and his comrades.

By relying on his knowledge of astronomy, Hanussen ensured the stars were routinely aligned in Hitler’s favor, and even predicted the Reichstag fire—home of the German parliament—that would mark the beginning of Nazi Germany.

But Hanussen was hiding one key truth: his Jewish identity. In fact, the clairvoyant was oblivious to the extent of the Nazis party’s plan he was guiding towards fulfillment.

Full of magic and the truth behind some of Hanussen’s greatest tricks, The Nazi Seance is an eye-opening, unsettling tale on the downfall of Germany—from the perspective of a man who played a key, yet unexamined, role.

For a sneak peek at the fascinating life of Erik Jan Hanussen, read on—then download the book today.

CHAPTER 1

One of the Finest Liars in Europe

In 1930, at the age of 41, Hanussen published his autobiography, Meine Lebenslinie (My Lifeline), the only account of his early years. Meine Lebenslinie reads like a Horatio Alger novel grafted onto amateur metaphysics and stale legends from show business. As our only source for Hanussen’s life before he became famous, it should be approached with a jaundiced eye. If you can consider it an album of Hanussen’s whims and imagination, it’s a fun read. Otherwise, it’s simply the jottings of an already puffed-up showman puffing himself up some more.

Throughout Meine Lebenslinie, Hanussen tells us that he was a genius at manipulating people, even as a baby. “I made my parents marry,” Hanussen proudly declares, looking back on his parents’ elopement in 1889. His mother, 20-year-old Julie Kohn, was pregnant by Siegfried Steinschneider, who was 11 years her senior. Outraged, Julie’s father, a wealthy furrier, tracked the couple down and had them arrested, Hanussen says without explanation, for vagrancy. Hanussen narrowly missed being born in a prison cell in Vienna: his mother was released 15 minutes before his birth.

Next in Hanussen’s infantile manipulations was “bringing my parents back together.” His father escaped from prison, climbed over the garden wall surrounding his in-laws’ house, and searched their villa for his wife and child. When young Hermann began crying wildly, Siegfried used the wailing to locate Julie and the baby. Her family was so busy quieting Hermann that they didn’t realize their son-in-law was in the house. Using the baby’s crying as a distraction, Hermann’s father grabbed “my mother’s hand and disappeared with her.” A few hours later, Siegfried returned, “took me by my diaper and kidnapped me. Smart little boy that I was, I didn’t make any noise.”

This baby was wise beyond his years. He united his parents, then helped his father save his mother from her cold, mean family. From conception on, he was a savant—even in soiled diapers.

Hanussen’s parents traveled constantly: His father was an actor, his mother, a singer. Roaming through Austria and Italy with low-budget troupes, they never made much money but always took baby Hermann with them. When he was three, his parents worked at a theater in Hermannstadt, a city in central Romania. The Steinschneiders lived in the rear of a house that faced “Corpse Alley,” a narrow lane leading to a cemetery. Every day, funeral corteges passed by, filling the air with dirges, grief, and gloom. One night young Hermann woke up with a start and ran “as if led by an invisible hand” to the nearby apartment of his favorite playmate, Erna. Leading her to the cemetery, he told her to crouch behind a tombstone. Seconds later, Hanussen wrote in Meine Lebenslinie, “there was a terrible explosion” in Erna’s parents’ apartment. Luckily, no one was hurt. This, Hanussen said, “was my first experience of clairvoyance.”

Hermann’s second experience with clairvoyance came soon after that. Every day he rode out to the countryside with a man named Martin, who hauled dung from the town’s stables in his wagon to the fields of the local farmers. One day a storm approached while Martin was heaving dung onto a field. Grabbing the reins, Hermann yelled, “Go!” Seconds later, lightning struck the tree the wagon had been standing under.

Looking back at these incidents with Erna and Martin, Hanussen said in Meine Lebenslinie that “the gift of clairvoyance is recognized early in someone’s life.” Maybe so, but more revealing is that, from an early age, Hanussen did not trust females. Not long after he saved Erna, she “let me down. A glazier moved into our building with his two sons. From that moment, she never looked at me again. Women are evil!” To Hanussen—as a boy and as a man—women were fickle and unreliable. It was better to leave them before they left you. In Hanussen’s account, little Erna was the first of many females who would give him a lifetime of headaches.

After a few months in Hermannstadt, Hanussen’s family returned to Vienna, always one step away from poverty and crammed into an apartment so tiny that Hanussen called it a “cabinet.” They were not the only Jews in Vienna who were poor, but it may have seemed that way. The Rothschilds lived there, most of the city’s doctors and lawyers were Jewish, and Jewish professionals were so well integrated into Viennese society—top to bottom—that even women in the royal family consulted a Jewish obstetrician. To a considerable degree, a frantic compulsion to assimilate accounted for the success of these Jews. The city had the highest conversion rate of any Jewish community in the world. It also had some of the worst self-hatred: Vienna’s second-richest Jew—the banker and railroad builder Baron Maurice de Hirsch—vowed “to prevent Jews from pushing ahead too much,” and an influential critic, Karl Kraus, himself a Jew, urged Jews to abandon their beliefs, their rituals, their mannerisms—anything that made them distinct and separate.

The Steinschneiders rarely had time to think about how they fit into the broader world. Their life was a constant struggle, partly because Siegfried had no trade from which he could earn a reliable living. About all he could peddle was his gift of gab. That was how he had wooed Julie and how he was now trying to survive as a salesman. But the Steinschneiders never forgot they were Jewish, and they didn’t let little Hermann forget either. Yet there is no indication that the local community remembered them, that any shuls or Jewish welfare organizations reached out to them. Or, indeed, that Siegfried or Julie sought their help. If anything, they were alone and drifting into an oblivion that was made worse when Julie died in 1899. She was 30 and had been sick for months. Hermann was nine.

To attempt to escape their poverty and their grief, Siegfried and his son moved to Boskovice, a small Czech town about 160 miles away. They were happy to be out of Vienna. And there, it seems, young Hanussen learned how to excel at the kind of pranks that would be the basis for his more sophisticated tricks in later decades.

After reading about the Roman emperor Nero, Hermann got the idea of doing to Boskovice what Nero had done to Rome: burn it down. Early one morning, he and some friends stole some paint and brushes, smeared “Rome Is Here” on most of the houses in town, and set fire to an old mill. As the villagers gathered to watch the fire, Grasel, a notorious thief, ran out of the mill. The police had been searching for him for months. The daughter of a local tailor also ran out of the mill: Grasel had a gift for seducing women. Hermann was immensely pleased with himself. “Boskovice of all cities,” he wrote in Meine Lebenslinie, “had the honor of catching Grasel. I was the hero of the day and, normally, I would have qualified for the reward.”

But the circumstances are not normal when you’re an arsonist. Hermann received five ducats—not the hundred-ducat reward the government had offered for Grasel’s capture. The boy also received a beating from one of his teachers—25 strokes with a cane. As an adult, Hanussen tried to be stoical about this. “God knows,” he wrote, “there are always two sides in life. On one side, there was the friendly community with the ducats; on the other, the strict teacher with the cane.” As the mill went up in smoke, so did Hermann’s faith in fairness. Grasel had terrorized towns and villages. Hermann had caught him. Those hundred ducats were his, he figured, even if he had started a fire that threatened the town. Instead, he was caned. If any lesson stayed with him, it was that justice has its limits. Meeting the law halfway, at best, was preferable to observing it strictly. After his mother died and his father could barely provide for them, after receiving only five ducats of the promised hundred, and after his teacher caned him, Hermann concluded that the only person he could rely on was himself.

Or so it would seem—if Hanussen was telling the truth. There had been a bandit named Grasel. Unfortunately, he was hanged in 1818—eight decades before Hanussen said the man ran out of a burning mill in Boskovice. The real Grasel came from a family of thieves: His grandfather, his parents, and at least one cousin all had been jailed for stealing. Grasel first went to prison when he was nine years old. When the police caught up with him a few decades later, they charged him with 205 crimes, including a few murders. Sixty thousand people watched his hanging. Few of them heard his last words: “So many people.” Hanussen also had a vocation that attracted people, though he never attracted a crowd as large as the one that watched Grasel’s hanging. Fueling Hanussen’s career was a deep and unshakable conviction that he could outsmart everyone—little Erna in Hermannstadt, the rubes in Boskovice, and, eventually, the audiences that filled the theaters where he performed and the Nazis who were conspiring to seize Germany. Like Grasel, Hanussen was not humble. Unlike Grasel, he would not hang. His enemies would find another way to deal with him.

Hermann and his father returned to Vienna three or four years later. Around this time, Hanussen had a bar mitzvah, although he does not use that term in his autobiography. Rather, he says, he had a confirmation. Confirmations for Jewish girls had begun in the mid-nineteenth century in Vienna, but they still were rare by the time Hanussen was of bar mitzvah age, which would have been about 1903. And anyway, boys were not eligible for them. Yet in those years some Viennese Jews referred to bar mitzvahs as confirmations, perhaps to draw less attention to their religion. Hanussen may have used the term in his autobiography for that exact reason. Nowhere in Meine Lebenslinie does he state that he was Jewish. That would have been bad for business.

Hanussen does state in Meine Lebenslinie that his father soon remarried—and that Hermann despised his new stepmother. Desperate to get away, Hermann thought he found his escape with a singer who performed in the garden of the Red Pretzel, a tavern just below the Steinschneiders’ apartment. She performed every night, and Hermann had a great view of her show. She was pretty. She was talented. And she was 45 years old. That didn’t stop 14-year-old Hermann. The lovers decided to run away, but they needed money. Ever resourceful, one afternoon Hermann lowered most of his family’s possessions—vases, pictures, bookcases, clothes—by rope into the tavern’s courtyard, where his lover was waiting. Then he shimmied down the rope. Hermann was almost to the ground when his father came home.

Even more than Hanussen’s story about Grasel, this foiled elopement carries the whiff of fiction: A 14-year-old’s fling with a 45-year-old is buffoonery, the furniture lowered to the garden is nonsensical, and the father’s brilliantly timed return home is farcical. The whole scene is pure slapstick—a nod to what had not yet been viewed on the screen in 1903, which is when this incident allegedly occurred. Not viewed because, in 1903, no one was making films like this. But it is similar to films that Hanussen would have seen by the time he wrote Meine Lebenslinie—two-reelers with Charlie Chaplin, Buster Keaton, or the Keystone Kops, extended skits that played fast and loose with logic and common sense, all of which the adult Hermann Steinschneider enjoyed twisting to his own benefit. For his elopement story, Hanussen lifted a trope from silent films and inserted it into his own life. It lends his teen years a certain glamour. Unfortunately, it was as real as the tricks that he later performed: riffs on a reality that he conjured up. Whatever Hanussen’s inadequacies, he more than compensated for them by concocting a convincing land of make-believe.

If Hermann couldn’t be with the lovely singer from the Red Pretzel, then he would follow her in another way: He would become an entertainer. So not long after his father stopped him from running away with a woman three times his age, Hermann asked the manager of a vaudeville show passing through Vienna for a job.

“Have you worked anywhere else?” the manager inquired.

“Of course,” Hermann lied. “I’ve been performing for five years.”

“Then you must have started very early.”

“I’m a natural,” Hermann blustered. “It runs in my blood.”

The manager told Hermann he could try out that night. He ran home, pawned all his clothes, and bought a tuxedo with tails. At a hairdresser’s, he traded the watch he had received for his bar mitzvah for a wig and a phony beard that he was sure would make him look funny that night. Fueled by coffee and strudel, he sat at a café jotting down jokes for his routine.

The show began at a tavern at five o’clock. Wearing his new tuxedo, wig, and beard, Hermann grew anxious as the night wore on, wondering if he would ever be called onstage. Around midnight, he asked the manager when he would have his turn.

“Oh, you still want to perform?” the manager said. “All right, go on stage and do your stuff.”

Hermann climbed the few steps to the stage, looked around nervously, and blurted out a few jokes. They fell flat. He tried some more. No one laughed. Finally, a long hook came out from the side of the stage, ending Hermann Steinschneider’s debut in show business. The only joke of the entire incident occurred the next day when his father couldn’t figure out why his son was wearing a tuxedo to school.

Again: an improbable story in Hanussen’s autobiography.

And again: Hanussen manufactures his own world—one part fantasy, one part moxie, one part making his father look like a jerk. Throughout Meine Lebenslinie, Hanussen accorded his father no respect. Calling him “My Old Man,” Hanussen mocked and belittled him as having no trade and no skills, no place in the world and no place in his son’s heart. There was a total lack of affection between the two, according to Hanussen’s account of these years. Weak, frail, and gutless, Siegfried served only one function for young Hanussen: he provided a model of what Hermann would never be. And as he had with his father, Hanussen would repeatedly relish bringing down to size anyone who was stronger, older, or wiser than himself.

Hermann’s debut as a comedian at that tavern was a flop, but after having his moment in the spotlight, he couldn’t turn away from it. A few months later, he ran away from home, hoping to get by on writing songs and funny monologues, briefly joining a circus, then a theater company in Neustadt, a town about five hundred miles from Vienna. He hated the director. “There have been many times in my life when things didn’t go well for me,” Hanussen wrote in Meine Lebenslinie, “but it’s never been worse than with director Bill.” He also hated Bill’s son, Ferdinand. One night, Hermann and Ferdinand began arguing while performing in a skit as army officers. Pulling out the sabers that were part of their costumes, they stabbed each other in front of the audience. Hermann was immediately fired.

For days, Hermann wandered around town. A prostitute, realizing that here was someone in even worse condition than she, gave him her last few coins. Desperate to buy a meal, Hermann drifted from tavern to tavern, telling jokes and hoping for handouts. He got schnapps, beer, and wine, but no one gave him a cent, and his pride stopped him from outright begging. “You must keep in mind,” he assured the readers of his autobiography, “that I was no vagabond, but an intelligent guy from a good family.”

He slept wherever he could—once in a kennel next to an oversized dog. He worked in the fields for a day or two and wasn’t asked to return—he was no good at manual labor. He worked for another theater company. No one came to its shows. The actors weren’t paid. They slept in the fields. They were all as hungry as Hermann. Finally, a circus took him in, almost as a charity case.

“Look, boy,” Mr. Pilcher, the director, told him, “you’re young and you need something to eat. Hungry bones only end up being living dirt. Real actors may look down on us as imposters, but we work hard so we can eat. And we always do.”

Hermann learned enough about the circus to fill many roles and to earn his keep. Sometimes he would negotiate with local officials for rental space for the circus. Or he would be “Harry, the famous bareback rider.” Or “Marini,” a gymnast. Or “Mr. Gari, the famous tightrope walker.” Or “the unbelievably funny clown, Mr. Clapp-Trapp.” And once, as “the famous actor, Hermann von Brandenburg,” he played Judas in a passion play. Of all the jobs Hermann Steinschneider had with the Circus Oriental, this was the most delicious: a Jew playing the Jew who betrayed the Jew who was the Son of God.

At the time, many small troupes like this were bouncing around Europe. Most had no more than a comedian or two, a strongman, a few horses, a monkey, a clown, a juggler. Some had a tent; most didn’t. And many, like the one young Hermann joined, were run by Gypsies, who, Hanussen later said, were his “best friends ever.” The best of his best friends were an odd couple: a giant and a pony. Heinrich the Giant was so tall Hermann barely reached his shoulders. They hung out all day, went to taverns at night, and slept in the stable, where Hermann doted on a pony named King, lovingly grooming him and bringing him fresh food he swiped from the fields while returning from his nightly carousing. A grateful King let Hermann rest his head against his soft, warm belly at night, barely moving so as not to wake his devoted friend.

This was the most idyllic time of Hanussen’s life. He was relaxed. He wasn’t always trying to prove himself. And for the first time in his life, he was receiving unwavering and unconditional love. Heinrich the Giant protected him “like his own blood.” And of his pony, Hanussen wrote, “King, my sweet King,” there had never been “comrades who understood each other as well as we.” After miles of wandering and years of loneliness, Hanussen found a home—in a stable.

* * *

This peaceful interlude ended, as these things often do, because of a woman. In a small village, Heinrich fell in love with Anna, the daughter of a brewery owner. The strongman was always sighing “like an elephant” over her, and Hermann, barely into his teens and with no appreciation for the powerful and unpredictable ways of the heart, couldn’t stand it. His strongman was now a weak man, and a girl—of all things—had done this to him. One day Heinrich, who was illiterate, asked Hermann to write a love letter for him. Determined to end “this unbearable situation,” Hermann sent Anna a note ending the romance.

Heinrich was furious, and Hermann was devastated. “The whole incident was a true disappointment to me,” he lamented. “Our whole friendship was ruined by a skirt.”

One night, after the wagons were loaded, Hermann hid in the bushes, watching the circus rumble out of town “until my eyes hurt and a cloud of dust covered the entire caravan.” When the dust settled, Hanussen stood up, took a deep breath, and decided he was ready “to rejoin civilization.” Unfortunately, civilization wasn’t ready for someone whose skills were limited to getting into fights, sleeping in stables, and betraying Jesus in a passion play.

Again, Hermann wandered aimlessly. He was down to his last few pennies when he saw an ad in a paper:

Zookeeper Wanted

For Animal Training

(Lions, Tigers, Dogs, Polar Bears)

Candidates must have experience as tamers and be able to present the ensemble in afternoon shows

At the circus—a huge enterprise with a hundred employees and a long caravan of wagons and even its own chapel—Hermann located the manager, who sized up the scrawny teenager.

“Have you done this kind of work before?” he asked.

“Of course.”

“And you’re familiar with training animals and presenting them in a show?”

“Of course.”

“Good. Then go talk with Mr. Johnson. He’ll show you the animals.”

Johnson may have been one of the more famous lion tamers of the day, but he was a complete coward around his wife, Mabel, who was small, skinny, cross-eyed, and, according to Hanussen, all seeing and all knowing. One eye looked to the right. One eye looked to the left. “She saw everything and she missed nothing,” Hanussen wrote. “The poor guy had a hard life with her by his side,” which may explain why Johnson was a lush.

Hermann fed the lions—from outside the cage. On his fourth day with the circus, Johnson got drunk. Barely able to stand, he draped one of his beefy arms around Hermann and walked him over to the lion’s cage. “I can’t do the show,” he said. “These beasts lunge at me when I’m drunk.” But Hermann could do it. “You’ve seen everything you need to know,” Johnson assured the young man. “You can wear my costume. When the lions smell a different costume, they attack whoever’s wearing it.”

Johnson’s only advice was to keep an eye on Sultan, one of the more feisty lions: “If you walk past him, he’ll try to grab you with his paw. Crack the whip and lash him until he stands on his pedestal and quiets down.”

Hermann went to the dressing room, got into Johnson’s costume, and ran his hands fondly over the epaulettes. “What can happen to me?” he thought. “I’m wearing Johnson’s costume.” He treated it like a talisman that could save him from whatever he was walking into.

The other performers formed two lines for Hermann to walk through to the cage. He marched bravely toward the lions, entered the cage—and froze: there was no way Johnson’s costume could protect him from these monsters. Then he realized that the lions already knew what to do. He just had to follow their lead. With every crack of his whip, they did what Johnson had taught them. Then Hermann got cocky and started shouting at them. They roared back and Sultan, the lion Johnson had warned Hermann about, refused to balance on a ball Hermann rolled in his direction. As the boy walked up to Sultan to scold him, the lion roared and swatted at him. Remembering what Johnson said, Hermann slapped Sultan across the face with the handle of the whip. Sultan winced, sighed, and, to quote Hanussen, “mumbled an apology.” Indeed, Hanussen would humbly assert, “It was like this always is in life: the bolder one wins.” Sultan returned to being docile and Hermann—a kid who had no idea what the hell he was doing—was temporary ruler of these dangerous beasts.

Hermann had always thought of himself as a hero. Now he was one, and it felt good. But as he was about to take off Johnson’s costume, he caught himself in the mirror: He was pale and white. He wasn’t a hero. He was just a scared kid. Then he looked at the outfit he was wearing. It wasn’t Johnson’s costume; he was wearing the tightrope walker’s tights. He “began shaking so much” he had to sit down, realizing he “was lucky not to have come across this mix-up five minutes earlier when I beat Sultan in the face.”

Hermann learned one principle from the debacle: “Imagination and fantasy are the only thing that count in life.” Finally, he was being honest with the readers of Meine Lebenslinie. It’s preposterous to think that he ever walked into a cage of lions. He may have worked as a lackey at a circus, perhaps grooming the domesticated animals or feeding (from outside their cage) some of the more exotic ones. But it strains credulity that any circus would let a teenager walk into a cage full of wild beasts if its lion tamer was too drunk to perform. And Hanussen could not have run his hands fondly over the epaulettes before walking into the cage because there weren’t any, not if he was actually wearing tights.

Like any creative act, Hanussen’s yarns provide insights into their author. His literary drama came at the expense of fact. His writing was a device that, more than anything else, was intended to manufacture sympathy for himself but, when examined carefully, only bred suspicions about its author. Hanussen devoted his life to illusion, to conjuring up realities that were entertaining, mystifying, boggling. His autobiography is no exception. How he presented himself in print was consistent with how he presented himself onstage. But a life devoted to weaving illusions is not a reliable life, and one danger was that Hanussen risked fooling himself. If a life is constructed on a lie—and on a lie that is eminently successful—why pay any attention to the truth?

By now, we’ve followed Hanussen through the years when he had little fame and even less money. We’ve heard that he brought his parents together as an infant in Vienna; that he saved little Erna’s life as a tot in Hermannstadt; that he was a juvenile delinquent in Boskovice, setting fire to a barn and nabbing a famous robber; that as a teenager he courted a singer three times his age and walked into a cage full of lions. The list goes on. It will get longer, as you will soon see. All these stories come from Hanussen. There is no way to confirm them. During this phase of his life, no one was chronicling his adventures. A rascal and a scoundrel, he is always the hero of his stories: falling flat on his face, again and again, then redeeming himself, bringing the cheering crowd to its feet demanding more miracles from this undersize, underestimated maestro. He knew the world was not coming to him for truth. Illusionists and mentalists don’t dabble in truth. As Chekhov said, “Any idiot can face a crisis; it’s the day-to-day living that wears you out.” The world was coming to him for hope—the hope that life is more than what it seems, that we can survive the grinding exhaustion of the day-to-day–ness of our lives. If we grant Hanussen this intention, his fictions are more than fabrications; they are parables of what might be.

So we enter into a compact with the Hanussens of the world. We allow them to make us smile, to brighten our day, to jolt us into wonderment. In turn, we are their willing and compliant audience—a small price to pay for pleasure and, on a good day, an even smaller price for the joy of being amazed. Yet it is essential to recognize that even illusionists have ethics. As the preeminent American magician Teller told me, “A magician puts a frame of truth around his lies that prevents them from doing harm.” The illusionist is honest about his dishonesty, aware of how easy it is to persuade the gullible and tractable to be in awe of profound and esoteric secrets. Jewish law—for, indeed, Hanussen was Jewish—imposes a similar obligation: A magician must admit to having no special powers. Claiming otherwise muddies the holy and the mundane, the sacred and the fake. Later in life, Hanussen would forget about these obligatory confessions. That lapse would bring him great fame… and much trouble.

Want to keep reading? Download The Nazi Seance today.

Featured image: Pexels / Canva