If you have been paying attention to world news in recent weeks, you have probably heard of Alexei Navalny, an opposition leader whose fate has sparked protests in cities across Russia. The protests in Russia are the latest development in what is a much bigger story–one that ties into a history of spycraft and poison in Russia that runs all the way back to the days of Lenin.

The protests began in support of opposition leader Alexei Navalny, who has become known for his investigations and videos exposing corrupt Russian officials and politicians. Amassing a significant following over the years, Navalny has become an influential critic of Russian politics.

However, his vocal opposition has also made him a target of the Kremlin. Last summer, Navalny was poisoned while visiting Siberia. After collapsing, then slipping into a coma, Navalny was eventually medevacked to Germany. There, the German government identified Novichok, a Soviet-era nerve agent, as the cause of his sudden deterioration. After investigating his own poisoning, Navalny blamed the Kremlin and Vladimir Putin personally for the assassination attempt.

Related: 4 of the Craziest Assassination Attempts in U.S. History

Despite his near death experience, Navalny set out to return to Russia after five months away. Many waited in anticipation as Navalny arrived in Moscow, at which point he was immediately arrested in the airport. He has since been sentenced to three and half years in prison.

While the dramatic events surrounding Alexei Navalny have caught the world’s attention, his poisoning back in August was not entirely surprising, given the Kremlin’s suspicious history with poison.

Related: These Short History Reads Will Make You Smarter in a Snap

There have been a variety of similarly high profile cases in recent decades that point to Russia’s repeated use of poison against those they view as enemies. Some might remember the 2006 poisoning of the defector Alexander Litvinenko with radioactive polonium-210, or the 2004 poisoning of the former Ukrainian president Viktor Yushchenko during his presidential campaign.

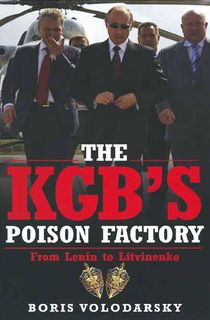

Tracing this pattern back through history, Boris Volodarsky offers a compelling account of some of Russia’s most notorious poisonings in his book, The KGB’s Poison Factory. As a former Russian military intelligence officer, Volodarsky provides unique insight, along with historical records, to illuminate the Kremlin’s long history with poison.

Read an excerpt from The KGB's Poison Factory below, then download the book.

In 2005 the Orthodox New Year, or the Old New Year as it is called in Russia and Ukraine, fell on the night of 13 to 14 January. Therefore, when I arrived at the Rudolfinerhaus clinic in Vienna and took a lift to the fourth floor to interview Nikolai Nikolayevich Korpan in his new office, I found him in festive mood. Dr Korpan, whom I had known quite well for several years, started by telling me that he had been invited to attend the Russian Embassy that evening to take part in the celebration. He did not plan to go but an embassy official called early in the morning asking him to reconfirm and adding that Nikolai Nikolayevich was considered a very important guest and His Excellency the ambassador himself was eager to see him. Korpan was proud and agreed to be there.

This talented physician, quite used to dealing with microscope and bacilli, could not know that during that reception he would himself become an object of a close, almost anatomical, study.

On the morning of 13 January University Professor Dr Korpan was a happy and confident man, well respected as one of the leading surgeons of a very prestigious private clinic in Vienna—the consultant-in-charge and in fact personal doctor to Victor Andreyevich Yushchenko, the president-elect of his native Ukraine. It was only weeks before this that Nikolai felt he had personally saved the future presidents life and helped in his own way to win the election.

Viktor Yushchenko shakes hands with Vladimir Putin.

Photo Credit: Wikimedia CommonsFour months earlier, on 5 September 2004, Alexander Tretyakov, a Ukrainian politician who used to be his patient some time ago, called Korpan’s mobile number in Vienna. Now a top aide of Victor Yushchenko, an opposition candidate running for the presidency, Tretyakov asked if Nikolai Nikolayevich could arrange a place in Rudolfinerhaus for a patient who would be coming that same day by a regular commercial flight from Kiev. Dr Korpan said he could.

There was no patient when Korpan arrived at Schwechat Vienna international airport that afternoon. Apparently Nikolai then got another call assuring him that his future patient – still unnamed at that stage – would be coming shortly. In his cosy office on Billrothstrasse in the upmarket 19th District, Korpan gave instructions for a reinforced night shift of emergency specialists and informed his boss, the Rudolfinerhaus president Dr Michael Zimpfer, a leading Austrian anaesthesiologist and critical care specialist, that they were waiting for a VIP, a very important patient.

Late that night another call came and Dr Korpan drove his small BMW to Schwechat again. Among the group of compatriots that arrived after midnight from Borispol in Ukraine were a woman, a child, three strong men and a very sick but rather handsome gentleman who introduced himself as Yushchenko. Dr Korpan knew very well who he was.

‘Doctor, I have a terrible pain in the back,’ he said after they shook hands. ‘Please, could you relieve me of it?’

Of course, but first they had to go to the hospital. They drove to the Rudolfinerhaus with Yushchenko lying on the back seat of Nikolai’s car and the others packed in Mercedes of Walter Komarek, an Austrian who had also come to meet them.

The ward was ready; a team of doctors got straight to work. It was 1:17 a.m.

They were not forensic experts but it was perhaps the best emergency team that Austria could provide. The laboratory tests had shown toxic effects in the body, so they immediately started detoxication procedures. The Ukrainian patient was given an endoscopy (but not biopsy) and was tested for Helicobacter pilori, with negative results. They found mucosal inflammation of the alimentary canal. Yushchenko’s liver and large intestine were affected as well as his skin and nervous system. But the doctors found to their amazement that all those symptoms seemed to show remarkable resistance to therapy.

More than a year before, in March 2003 with the presidential election campaign looming, the Kuchma government in Ukraine had shut down Radio Continent, a private station that re-transmitted programmes about the country and its current politics that were being broadcast by the BBC, Voice of America, Deutsche Welle and other Western outlets. The Ukrainian Service of Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty (RFE/RL), by giving the population news from the opposition camp, was becoming an important factor in the election campaign. The president of RFE/RL, Thomas A. Dine, told me in Prague that they were seeking collaboration with local stations in the former Soviet republics to reach listeners on easily accessible short waves (HM), and the Ukrainian authorities were not happy about it.

HM transmission required a government license, so Sergey Sholokh, Radio Continent chief executive, was called on the carpet and advised to review his policy. ‘The first thing they told me,’ he said later, ‘was that if I put RFE/RL on air, it would be the end for me and my station. But if I secretly collaborated with them, all claims against Radio Continent would end and I would have free rein with all the funds and support I needed. I agreed to their demands – to win time to escape.’ After Sholokh left the country, security forces raided the station, arrested three of his staff and took away broadcast equipment. ‘It was an act of revenge,’ Sholokh said, ‘because they understood they could not get at me physically. They wanted to destroy Radio Continent. This was simply an attack by bandits.’1

Later that year 2003 the authorities took other harsh steps to weaken the opposition. In October they thwarted Yushchenko’s attempt to chair his party congress in Donetsk, the stronghold of the pro-Kremlin Ukrainian politician Victor Yanukovich. A mob armed with bats and crowbars physically prevented Yushchenko from entering the town.

Viktor Yushchenko photographed in 2016.

Photo Credit: Wikimedia CommonsThe opposition leader then decided it was time to add security of his own to the two bodyguards the government had provided him. In early 2004 he appointed Evgeny Chervonenko, a former motor racing professional who had been an aide to President Kuchma until he joined the opposition, as coordinator of a special security detail to guard the candidate full time. Chervonenko had previously had nothing to do with security but he was devoted and reliable, second only to the candidate’s wife in the closest circle of Yushchenko’s friends and supporters, a man he could trust with his life. Chervonenko quickly added a team of more than fifty professionals to the State Protection Service (SPS) men attached to Yushchenko, Pavel Alyoshin and Peter Plyuta.

Chervonenko and his people were guarding Yushchenko and his family during their holidays in Crimea in the summer of 2004 when they spotted the police surveillance teams watching and even filming them. In the government dacha Chervonenko took upon himself the tasting of the food that was offered to Yushchenko.

While Yushchenko was vacationing in the Crimea, Russian President Vladimir Putin was also there attending a one-day business forum in Yalta where together with the Ukrainian President Kuchma and his Prime Minister Yanukovich, Putin was trying to promote the so-called Common Economic Space, a loose alliance encompassing Russia, Ukraine, Belarus and Kazakhstan.

Related: American Traitors: The Best Friends Who Sold Secrets to Soviet Russia

Speaking at this forum on 26 July 2004, Putin accused the secret services of Western countries of interfering with the Russia’s plans to integrate economically with Ukraine. ‘[Western] agents, in our countries and outside them,’ he said, ‘are trying to discredit the integration of Russia and Ukraine.’ The former Chekist used the word agentura, the KGB term for networks of secret agents that penetrated foreign countries during the Cold War on behalf of the Kremlin. That was a Freudian slip: speaking about a Western threat, the President of Russia was contemplating his own operations.

Yushchenko and his people returned from the Crimea on 19 August to prepare for the final stage of the presidential race.

On 28 August Vladimir Satsyuk, first deputy director of the Ukrainian Security Service (SBU) was spotted in Moscow meeting his Russian colleagues. During the same month Mykola Melnichenko was also in the Russian capital negotiating a deal with the SVR/FSB representatives. Upon his return to Kiev, Satsyuk arranged a meeting with the opposition leader Yushchenko at his dacha without delay.

It was David Zhvaniya, a Georgian member of and heavy donator to Our Ukraine (Yushchenko’s party) who had been approached to organise this secret meeting between the SBU leadership and the opposition candidate. Zhvaniya was a trusted person and one of two contact men in Kiev for Boris Berezovsky who was supporting and funding the Orange Revolution from his London exile.

Without seeing the files it is impossible, of course, to accuse Zhvaniya of working for the FSB. I have never seen any evidence that shows any involvement by Zhvaniya. This was suggested much later, in September 2007 after the poisoning of Yushchenko, when Boris Berezovsky sued Tretyakov and Zhvaniya, who had in the meantime became the emergency minister of Ukraine, for misusing nearly $23 million that the tycoon had allocated for Yushchenko’s campaign. And more importantly, Zhvaniya took a pro-Kremlin position and joined an FSB-orchestrated propaganda operation designed to prove that there had never been any attempt on the candidate’s life and all that happened in September 2004 was nothing but Yushchenko’s subterfuge aimed at bringing himself to power.

At the end of August, Yushchenko accompanied by Zhvania visited Satsyuk’s dacha to discuss the security measures during the final days before the elections. He was greeted by Satsyuk and served a friendly and substantial dinner of Uzbek pilaf and plenty of good wine. Serving the dear guest this way was without doubt a final test-run of Moscow’s operation to assassinate him.

Want to keep reading? Download The KGB’s Poison Factory now.

This post is sponsored by Open Road Media. Thank you for supporting our partners, who make it possible for The Archive to continue publishing the history stories you love.

[via: nytimes.com, msn.com, apnews.com]