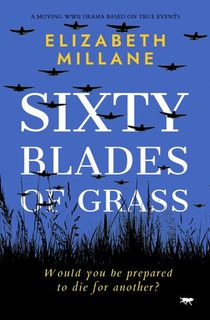

Helmed by brave rebels who refused to accept the Nazis’ invasion into their homelands, resistance networks snaked all across Occupied Europe during World War II. Members risked their lives to deliver supplies and crucial intelligence, as well as smuggle Jews and others in grave danger to safety. Some of these brave people were as young as teenagers. Sixty Blades of Grass, a new novel, focuses on Rika, a 17-year-old Dutch Resistance fighter.

Inspired by the author’s own family history, Sixty Blades of Grass follows Rika’s efforts to protect Rachel—her closest friend, a girl from a prominent Jewish family—as well as document the deportation of Dutch Jews by painting what she witnesses at the rail yards. But when she suspects her German-born father of collaborating with the Nazis, Rika realizes it isn’t safe to trust even her closest family.

For a sneak peek at this thrilling novel, read the excerpt below, then download the book today.

Below the tumult, the train station bustles. I hear shouts, the screech of the wheels on the iron tracks, the roar of vans and buses, the murmur of moving people. I strain to see it all, counting to myself as I watch our Jews shuffle along in long lines, lugging large suitcases and clutching children’s hands, scrambling onto waiting trains. I recognize some of the soldiers by the way they move, the way they wield their guns. I catch my breath when I see the butt of a rifle brought down and a person fall. The shout and crack I hear a second later. I continue to paint, counting again and again the people and the number of trains.

My task is to document, in code, how many Jews are taken, and which direction the train takes, but I must convey more; I have to show that the violence is escalating, that the Jews are resisting the transport. I am possibly their last witness, the last person in Holland to see them. Their last voice. This painting is the last thing the Resistance may learn about their departure on this transport.

I sweep every detail I can onto the paper, but my paint on the canvas shows something altogether different. Blades of grass appear, clusters of withered wildflowers, pebbles, and soil. There is turmoil over the ground, swirling, dark, menacing clouds, not the cold grey ones that hang over me. These clouds document that there has been violence, the Germans are beating Jews into submission, but the captured Jews are resisting the “relocation”. A sun withers behind the clouds, the last rays of light illuminating the stalks of poppies and cornflowers amidst a sheen of new grass. The watercolors dry fast in the cold, dry wind.

I view the painting a moment and my heart hurts as I count hundreds of my captive Jewish countrymen, gone today. What are the Germans doing to them? Where are they going? Will we find them again? Can any of the information in these paintings save them?

More detail to add: I count the transport cars and soldiers. I note the time it took to load their prisoners. All goes on the canvas. A slash of orange means they used cattle cars on this transport. Cattle cars to transport human beings.

I glance at my watch. Almost time to hide the painting under a piece of rubble, mark it with cake of paint. Another underground fighter will retrieve it later. My findings will be added to the information we have from other transport witnesses. Maybe all of it will lead us to these lost countrymen, so we can return them to Dutch soil, to their home again.

The whistle shrills, trains lurch, the cars clatter together, and I note the time with a few dots of rubble.

“Farewell!” I whisper to the passengers, my breath catching in my throat. Sadness descends on me, as it always does at this point in the assignment. I can’t move for a moment. The weight of what I have witnessed pushing me down, into the campstool. I breathe bastaards, and paint, on the left-hand side of the canvas, a golden leafless stem, bending as the train travels, to the east.

Then the rain, which has been spattering intermittently, starts in earnest. Time to hide the painting, go to Rachel’s house, my Jewish friend. She hasn’t answered any of my notes or calls. She might be gone on a transport already. Hurry, hurry, I tell myself, shaking off my lethargy and sadness. Get out of here. It’s time to see Rachel!

I fold the canvas, open the rucksack, and tuck away the damp brushes, the moist pans and paint spattered pallet. I pick up the jar and toss the dirty water behind me.

“ACHTUNG!”

Rika’s Diary

Rachel is my best friend. So what if she is Jewish? We Dutch don’t care, or most of us don’t. Rachel and her family are revered in Holland. Her father is a great surgeon, her mother from a great ancestral family, famous for her hospitality and generosity to causes.

Rachel is a musician, a violinist, really famous already.

It makes me furious, the way they’ve been treated! As if they’re a tasty tidbit for the Germans! The Germans are playing cat and mouse with them and have been since the occupation. Can’t Rachel and her family see it?

First, the German Reichskommissar, who controls all of Holland, assured them that, due to their prominent standing, they were protected. But Papa didn’t believe it. He went to see them. “Leave!” He pleaded, standing in their threshold. He begged them: “I can get you on a boat to England.”

But they have stayed, even though their friends disappeared. Last month the Reichskommissar became elusive about their status, and still they stayed. Of course, they were all humiliated when Rachels finance, Rolf, called off the engagement because she is Jewish. And then Rachel’s instructor refused to teach her any longer, telling her he has time only for true artists, ones with promise, with a future – well, only then did Rachel understand that she has no future in Holland. But it is all too late. I cry for her, every night.

~

I’ve run from the tram and need to catch my breath on the steps of Rachel’s house. Is she still here, or have the Germans come and taken her away? How stupid was I to come here? Will I be caught? I tremble and look up and down the avenue. Has the German officer, who found me painting, followed me? Damn! Have I led him to her?

The German in the rail yard was an officer, I could tell by his peaked hat. Blue eyes. Olive skin. I’d thrown the dirty paint water over his pants. How long had he been there, watching me paint? What did he suspect?

I prayed he bought my story. After I apologized, again and again, for ruining his pants, the lie rose to my lips and I found myself explaining what had brought me to the rail yard. I gestured at the weeds and dried flowers on the ground, telling him some were rare, a challenge to paint. I unfolded the painting to show him one of them, then crouched by the actual plant I’d rendered, fingering the brittle leaves. I babbled on about how my instructors always wanted me to find something unique in nature. The rail yard was undisturbed, I said, I could concentrate well there. My heart had pounded so hard I could barely hear what I said. I hoped my face looked as I had rehearsed – bland, innocent, open. Eyes wide. Behind my chatter I prayed he would believe me. He had to believe me.

Just before knocking I look around the neighborhood.

This is the most elegant section of Amsterdam. I take in the varied stair railings, made of finely wrought iron, the rare, imported facades of stone and brick, the soaring rooftops. On another day, in another time, I would have strolled the avenue arm in arm with Rachel. We would have admired the architecture, the details on the doors and bricks. We would have waved to neighbors who stood at their windows and waved back. Now, with fear I peered into the windows, and I knew that fear looked out.

Three German soldiers loiter on the corner, pacing and looking back and forth. One bends his head, and cups his hand to light his cigarette. I do not see the flame, just the spring back when he inhales, and the faint cloud of smoke that soars up into the wind. Monsters. What the hell are they doing here, in my country! Why are they at this corner, on this street, at this time? Their guns are slung onto their backs; I can see the shine of the barrels.

One more big gulp of air, I climb the stairs to the front door. My rucksack, heavy with my art supplies, digs into my shoulder. I readjust the strap by pulling it forward, which makes the long leather painting tube bat my head. Another twist, another knock in the head by the tube. I laugh and give up. The entire sack drops to my feet. It hits the granite steps with a muffled thud.

I raise my hand to knock on the varnished wood door, and stop. I can see my own reflection in the high shine. For a moment my hand seems like a salute, a raised fist of defiance. Ignoring the brass knocker, I rap on the bare wood.

There is a rustle at the window at the side of the door. The tip of a finger pulls the heavy curtain aside, then disappears. I pick up my rucksack and tube, ready to run if a German opens the door. I hear the locks click. The door opens. Rachel pulls me into the house, closing the door behind me.

“Rika!” She hugs me hard. For a moment, all is well. I press my face against hers and inhale.

A few strands of the glorious collection of curls and twists of Rachel’s hair find their way to my mouth. With my free hand, I pull them away. Oh Lord, it was good to see her.

“Rachel. Is it all right that I came to see you?”

“Of course, but I would have opened the door only for you.”

“You are still here.”

In a small voice Rachel says, “Perhaps not for long. We’ve been ordered to a transport.”

A transport!

My breath catches in my throat. I’d known of a few people who had disappeared and had learned later they’d been taken away on the transports, but not anyone so close to me, like this. The thought of Rachel, my best friend, my confidant, leaving, hits me hard, like a punch in the gut.

I know I can help her, but I also know I cannot be the one to tell her. How fast can I put things in motion? Is there time? I had to get to the University, as soon as possible. There is a contact there, an underground contact. I would have her come and see Rachel, immediately. With that plan in my head, I let myself look at her.

If I were a portrait artist, what a painting I would render of my best friend, this eighteen-year-old girl, who fusses with settling my painting clabber on this floor! Only oils would capture her brown eyes, the glints of gold in her hair, the luster in her olive skin. I recall the serenity in her face when she played her violin, and I composed a portrait of her, playing, just like that. “This may be the last you look upon her,” a voice inside my head says. Is it a premonition? A bad omen? Rachel turns to me and puts her hand to my hair, lightly touching the strands around my face. Has she heard the same voice?

“Come in, come in! I didn’t know if I should try to get a message to you, but I wanted to see you, before…” Her voice trails off. She grabs my hand and pulls me down the hall.

Everywhere in the long hallway are half-packed valises and tumbled house furnishings. Rachel’s violin lay on a table on top of sheet music. Was she taking it? Would she be able to play it, where ever she was sent?

Want to keep reading? Download Sixty Blades of Grass today!

This post is sponsored by Bloodhound Books. Thank you for supporting our partners, who make it possible for The Archive to continue publishing the history stories you love.

Featured image: Marjan Blan / Unsplash