The world wars of the 20th century redrew borders and reshaped the culture and politics of the world permanently. Yet the conflicts spawned from the bullets of Gavrilo Princip’s gun were not the first global wars in history. Over 150 years before World War I broke out, European powers were brawling in a conflict that spanned five continents. The Seven Years' War would have a lasting influence on politics and diplomacy for decades, even centuries to come.

The origin of the Seven Years’ War lies in both unresolved disputes that had been brewing in Europe for years and colonization of the Americas. France had laid claim to Canada and the Great Lakes region, while the Eastern Seaboard lay in British hands. Skirmishes between the French, British, and their various Native American allies were common throughout the mid-18th century.

This spilled over into outright war when George Washington, then a Virginia soldier, led a joint colonial and Native American force in an ambush of the French. The conflict left several Frenchmen dead and others captured in what became known as the Jumonville affair. The 1754 ambush had international implications and saw the French retaliate against the British.

Across the Atlantic, allies were changing partners like some sort of diplomatic dance. Prussia, then a German state and an ally of France, sided with Britain instead in hopes of gaining power over Austria; Austria then abandoned the British to partner with France. This realignment of alliances is known as the Diplomatic Revolution of 1756.

Meanwhile, Prussia preemptively annexed the state of Saxony in anticipation of war, which angered much of Europe, especially the other states within the Holy Roman Empire. The Russian Empire, fearful that Prussia’s ambitions could be turned to neighboring Poland and Lithuania, also joined in against Prussia. 1756 saw war officially declared against the French by the British, and the Seven Years' War began in earnest.

In contrast to the middling efforts of their British allies in the Americas, the Prussians were successful in that first year of the war. Despite being largely outnumbered, they were able to take over Saxony and protect their holds elsewhere. Yet an ambitious march into the Kingdom of Bohemia changed the tides for the Prussians, who were defeated in Bohemia and then forced to retreat after the Russians had taken one of their strongest fortresses.

Sweden saw its opportunity to get in on the action, declaring war against Prussia with the main goal of retaking its former territory Pomerania. Swedish troops occupied the region and did not expect to ever actually encounter Prussian forces, figuring they would be too busy with the numerous other war fronts.

A map of the participants in the Seven Years' War. Blue represents Britain and its allies; green represents France and its allies.

Photo Credit: WikipediaThe end of 1757 saw a massive French and Holy Roman Empire army approach the Prussians from one flank and professional Austrian soldiers approach from the other. Yet Prussian King Frederick II proved his skill as a general and defeated both forces, with some 500 casualties of his own to the French and Holy Roman Empire’s 10,000 at the Battle of Rossbach.

Meanwhile, Britain was just starting to find its feet in North America. It began paying Prussia a considerable annual fee and provided troops to help protect Prussian borders from French forces, though 1758 was a largely inconclusive year in the war.

1759

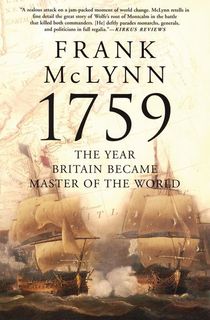

The year 1759 was dubbed by the British as “Annus Mirabilis" (otherwise known as the “Year of Miracles” or “Year of Victories”) due to a series of windfalls that spelled the French defeat. Author Frank McLynn dives into this singular year in great detail, leaning on primary sources from the Vatican's archives and Native American oral histories to prove not only how this year turned Great Britain into an empire… but also to examine how much luck played a part in its success.

The next few years of the conflict were exhausting for all involved. Prussia suffered such heavy defeats that Frederick was driven to suicidal thoughts and considered abdicating the throne. But problems with the Russian supply line, and defeats to the French that prevented them from aiding their Eastern allies, meant that the Prussians could hold on.

In 1762, the Russian Empress Elizabeth died, which would change the course of the war. Her successor, Peter III, was born in Germany and could hardly speak Russian. As such, he was sympathetic to the Prussians. He pulled out Russian troops, mediating a truce between Prussia and Sweden (which had long been routed from Pomerania), and even placed a corps of Russian soldiers under Frederick’s command.

In 1762, Spain was called into the war on the French-Austrian side. Its invasion of Portugal was initially successful, but the joint Franco-Spanish army was eventually driven back to Spain. Meanwhile, Britain was making significant gains in North America. Britain had focused much more on taking overseas territories from France and Spain rather than fighting on mainland Europe, winning in India, the Philippines, Cuba, Guadeloupe, Martinique, and Senegal. Britain’s naval superiority was vital in sieging these island states and blocking off supplies to France’s overseas troops.

In 1763, it was clear that Austria would not regain Silesia from Prussia, which was its main goal throughout the war. With this major player depleted and exhausted, along with the rest of the European armies, the end of the war on the continent was looming. The Treaty of Hubertusburg was signed on the 15th of February, in which Prussia was allowed to keep Silesia and would have Glatz (located in modern-day Poland) returned if they evacuated Saxony.

The Treaty of Paris, signed five days earlier, had an even bigger impact on borders. Though both sides returned some territories gained through conquest, Britain ultimately gained considerable land in North America and the Caribbean, including much of Canada, the eastern half of French Louisiana, and islands like Dominica and Tobago. As a result, Britain began its rise as the world's predominant colonial and naval power.

Painting of the Battle of Rossbach, a significant Prussian victory.

Photo Credit: WikipediaThat skirmish with George Washington in 1754 had led to violent clashes in North and South America, Africa, Asia, the Pacific, and Europe. After seven years, the global conflict was finally over. Though it led to redrawn borders and territory holdings, the greatest legacy of the war was not geopolitical, but financial. Nearly every power involved suffered major monetary losses during the Seven Years' War; Maria Theresa of Austria even had to pawn her jewelry to keep her country’s coffers full.

Britain was able to fund its own escapades, but that came at a price. The British were able to pay Prussia by heavily taxing their American colonists. This soured the image of the Crown for those across the Atlantic, made only worse by the fact that nearby Native nations had been provoked by the hostilities. While the British were able to pack up and go home, the colonists were left to deal with increasingly fractured relationships with their Native American neighbors. To this day, Americans commonly refer to the Seven Years' War as the French and Indian War, highlighting the significant participation of indigenous forces.

The roots of rebellion were taking shape on American soil, and when the American Revolution broke out around a decade after the Seven Years' War, France was able to get its revenge against the British by supporting the Americans against their mutual rival. Though the immediate aftermath of the Seven Years' War was mild compared to the two World Wars that would follow over a century later, it paved the way for Britain to lose one of its most powerful colonies, which would ultimately change the course of world history.

More Great Reads About Conflicts in the Seven Years War

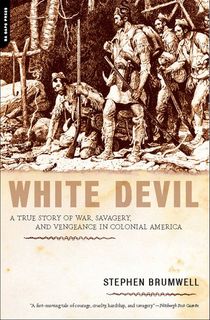

White Devil

The St. Francis Raid that took place during the French and Indian War is perhaps most memorably depicted in James Fenimore Cooper's The Last of the Mohicans. After the massacre of the garrison of Fort William Henry, the British were eager for revenge. Major Robert Rogers and his men were sent north to get it.

Book Review Digest called Stephen Brumwell's account of the events “fluid, well-paced, and sprinkled with intriguing details…. Evidence of painstaking research is presented.”

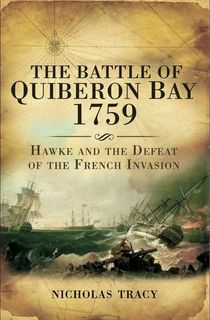

The Battle of Quiberon Bay, 1759

For those seeking more European history, consider Nicholas Tracy's account of the Battle of Quiberon Bay, which, like so many of these events, took place in 1759. Fearing invasion by French ships, Admiral Edward Hawke helped to establish the British naval dominance that we recognize today. Not only did he intercept the invaders, but he pursued them, destroyed their ships, and captured their men. Often overlooked, the Battle of Quiberon Bay was an important and decisive victory for the Royal Navy.

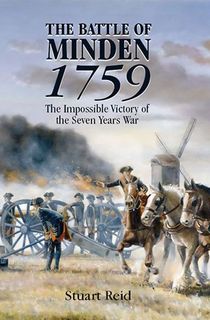

The Battle of Minden, 1759

A major engagement of the Seven Years War, the Battle of Minden pitted Britain and her German allies against the French. The battle, which proved to be a British victory, held no end of intrigue. Not only did mistaken orders play a major role in the combat, but one commander was court-martialed for ignoring repeated orders.

Author Stuart Reid dives into not only the Battle of Minden but the greater context of previous British campaigns, giving readers more insight. Where the Battle of Quiberon Bay helped to establish British naval dominance, this victory by land proved a major boost of its infantry and firepower.

Sources: History.com, Office of the Historian