U.S. Air Mail and the ease with which it operates today resulted from quite a humble beginning. Air Mail operations came underway less than a decade after the Wright Brothers took to the skies, and along with primitive resources and pilots with very limited flying experience, the Post Office Department also had to organize Air Mail services from scratch.

At the time, it was straightforward to send mail by boat or train, as the Post Office Department could simply contract out the work to private companies and they wouldn’t have to expend too much time, resources, or organizational strategies. But because Air Mail was a new concept, there were no private contractors to contact; so the Post Office Department initially employed the Army to send Air Mail before eventually proving Air Mail’s value and implementing a training program and raising enough funds to build their own program.

Air Mail technically began in 1918, but developments began almost a decade before in 1910. A bill authorizing the Postmaster General to look into the possibility of an airship mail route was proposed in 1910, but died in committee. However, Frank Hitchcock, Postmaster General from 1909 to 1913, was largely interested in airplane development and was confident it could be used for this cause. So he authorized experimental air flights at aviation meets and other events, until the Department could convince Congress to invest the money needed to start an Air Mail service.

The service started small in May of 1918 with very limited routes, and by 1920, radio stations were installed at each airfield to warn pilots of the weather. This was also the year that the first transcontinental air route from New York to San Francisco was initiated, resulting in mail being delivered 22 hours faster than by train. By 1924, the heroic efforts of pilot Jack Knight (who successfully flew a test flight at night through a blizzard) resulted in regular night flying, regular cross-country flying, two Collier Trophies to the Post Office Department for their contributions to aeronautic development, and over one million dollars from Congress to support the expansion of Air Mail services.

By 1926, the Post Office Department was able to invite bids from commercial aviation companies for airmail services. At this time, the Department transferred their lights, airways, and radio service to the Department of Commerce. As commercial aviation companies took over, and expansion progressed, planes began to take on passengers. International airmail became steady in 1928, transpacific routes steady by 1935, transatlantic routes steady by 1939, until airmail as a separate class of domestic mail officially ended in 1977.

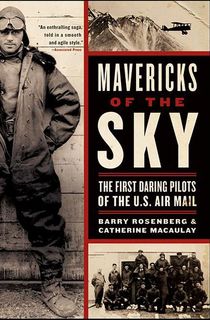

Mavericks of the Sky is a narrative nonfiction chronicle of the early years of air mail service from 1918 to 1921. It begins with the first flight from New York to Washington, D.C. in 1918, and ends with Jack Knight’s courageous flight in 1921. Telling the story of the extraordinary lives and rivalries of the brave men who could rely only on their wits and instincts to stay alive amidst the threats of weather, mechanical failure, and limited training, readers get to read first-hand about their contributions to the airmail services we know and love today.

If you'd like to learn more about U.S. Air Mail's origins, read an excerpt from chapter three of Mavericks of the Sky below.

Above the fold on the front page of the next morning’s Washington Post, sandwiched between the story “French Take Hill 44” and “Strong Shellfire on Italian Front,” screamed the headline that Praeger and Burleson had worked so hard to achieve: “Aero Mail a Success.”

As a former newspaper reporter, Praeger understood the value of story placement, and nobody could deny that the headline spoke volumes. Truth be told, though, the second assistant postmaster was lucky that the Post hadn’t printed all the details of Boyle’s inaugural flight, choosing instead to limit most of the bad news to subheads in the story.

“Capital Plane in Mishap,” read the first.

“Lieut. Boyle After Going 30 Miles Forced to Descend in Maryland” went the second, followed by “Loses Way in Misty Sky, Has Engine Troubles and Breaks Propeller in Coming Down.”

It seems the rookie pilot had dutifully followed Fleet’s orders to parallel the railroad tracks out of town; the problem was, he’d followed them in the wrong direction. The realization hit him eventually, and in need of directions he set down in a field near Waldorf, Maryland. Too late did he grasp his mistake, though, the field being newly plowed. His wheels sank into the brown, earthen gruel, throwing his ship onto its back like a bad gymnast. Boyle emerged unhurt, but the Air Mail Service had dished up its first casualty less than twenty minutes into its inaugural flight.

But what did that matter. The rest of Fleet’s team conducted themselves flawlessly that day.

The mustachioed, young Lt. Howard Paul Culver was waiting at Bustleton to fly the second northbound leg when he heard of the rookie’s fate. He immediately climbed into his cockpit and drove his plane into the sky. There might not be any Washington mail in that cargo hold, but throngs of people were awaiting the arrival of a U.S. aero mail plane at Belmont field, and Culver did not intend to disappoint.

Ninety miles later, Culver’s ship approached the airspace over Long Island. In the distance, two military chase planes were flying lazy circles in the sky, a rendezvous having been arranged by the military brass at nearby Mineola. With his arrival, all three planes joined in a V formation and proceeded to make a slow pass over the racetrack. Shouts rose from the grandstand as the sight of American planes flying as a single fighting unit overhead, its centerpiece a boldly painted mail plane with five-pointed stars under its wings, caused patriotic hearts to race. Who cared that President Wilson’s letter and all the other mail from Washington was lying upside down in a Maryland field. It was the feat being honored; it was the daring young flier being cheered.

Lt. Torrey Webb’s flight out of Belmont created similar thrills for the thousands of people filling the grandstand and infield in anticipation of the first regularly scheduled airmail flight from New York to Washington. Everyone watched as a whistle-tooting Long Island Railroad train pulled into the station adjacent to the raceway. Onboard were two precious sacks of mail, which were quickly transferred to a waiting flivver that then sped across the expanse of grass to the mail plane, where its clean-shaven leather-jacketed pilot stood waiting.

Webb’s new wife stood proudly by and watched her husband help stow the mail in the hopper just forward of the cockpit. Much of the crowd, however, was distracted by the ongoing speeches. One after another, postal officials, politicians, and dignitaries took to the podium to wax lyrical on the state of aviation. Webb found himself growing increasingly anxious. Their eyes were on the future, his were on the clock. Maj. Fleet had given him direct orders to have the ship in the air no later than 11:30. Webb didn’t want to disrupt the ceremonies, but he was first and foremost an Army flier. An order is an order.

The prop was spun and the engine thundered to life. Field personnel grabbed hold of the wings to steady the plane as it slowly taxied to the end of the infield, face into the wind.

Someone yelled, “There she goes!” and all heads turned to see Webb barreling down the infield, throttle forward. A children’s choir from Queens began to belt out “The Star-Spangled Banner” as Webb’s plane swept past the stage, drowning any vestige of oratory from the podium. People cheered and waved their hats as the Jenny continued its charge across the infield until its wheels lifted from the ground, sending the pilot skyward.

New York City postmaster Thomas G. Patten with airmail pilot Lt. Torrey Webb.

Photo Credit: Wikimedia CommonsWebb leveled off at 4,000 feet, then set a course for Philadelphia, fully 144 pounds of U.S. government mail stowed inside his aircraft. Behind him, the racetrack receded from view, its boundaries merging into the eye-stretching vista around him. The Jenny continued down Long Island toward Manhattan, crossed over New York Harbor, softly rising and falling over the eddies of air. It wasn’t long before northern New Jersey passed beneath his wings, thick plumes of smoke rising from its factories and refineries. The gray changed to green as the farms of central Jersey dominated, and the elegant fieldstone towers and buildings of Princeton University offered a welcome marker to the pilot above. For Webb, graduate of another prestigious ivy-covered university, the panoramas of flying were a world away from the subterranean depths he’d been educated to plumb. The passing towns, the schoolyards, the narrow dirt roads were merely etchings on a flat two-dimensional surface over which he was moving, with as many marvels below the surface as there were from nearly a mile up.

The lieutenant touched down in Philadelphia an hour later without cracking up, getting lost, or running out of fuel, ready to pass his mail sacks off to Lt. James Edgerton who, just six minutes later, was airborne, winging his way toward the nation’s capital.

Soaring over Delaware and Maryland, he arrived in Washington to find Potomac Park still crowded with people, many of whom had stayed to enjoy a picnic and catch the day’s second show. The field, already small, was dangerously hemmed in by the swell of spectators. Edgerton sized up the situation, then chose a landing pattern that would get him down without getting anyone hurt.

“I decided on a southern approach … a side slip to kill forward speed … no brakes or flaps … better slip to the left away from the crowd … quick, the right wing tip must just clear the bandstand … a twitch on the stick to straighten out … stalling speed, down with the tail … and a three-point landing.”

The florist shops in town did well that day. Edgerton landed both wings up, and waiting for him there was his younger sister, her arms clutching an enormous bouquet of roses, her face warmed by a shy smile. Fleet, too, was on hand to greet the pilot and offer his “well done.”

Then, with all due speed, mail sacks were loaded into an idling automobile-truck for quick dispatch to the city’s main post office where a platoon of Boy Scouts on bicycles stood ready. Less than a half hour later, all the youngsters had managed to ply their considerable enthusiasm and pedal power into successful delivery of nearly 750 pieces of mail, including one from the Postmaster General Burleson, personally addressed to his good friend Alan Hawley, president of the Aero Club of America, thanking him for his unfailing support throughout the entire protracted effort. Organizations like the Aero Club had been fervent supports of aviation— stirring up the possibilities of everything from airmail to crossing the Atlantic Ocean by airplane.

Make no mistake, said Burleson in his note of thanks to Hawley, the first airmail flight marked “the beginning of an epoch in the development of speedy mail communication.”

Want to keep reading? Download Mavericks of the Sky today!

Sources: USPS, Smithsonian, History.com