At the turn of the 20th century, young African American jockey, Jimmy “Wink” Winkfield, seemed destined for greatness as he rode to victory in two successive Kentucky Derbys, only then to be hounded out of the sport because of racial discrimination. In a classic rags to riches tale, the diminutive Winkfield fought back to enjoy unprecedented success as a jockey and trainer overseas, but life was rarely straightforward for this legend of the horse racing world. Along the way, he had to draw upon all his considerable resilience to survive some of the 20th-century’s most seismic events, as well as ongoing prejudice back home.

Winkfield is generally believed to have been born in 1882. He was raised in Kentucky’s Bluegrass Country, a world-renowned center for thoroughbred horse racing and breeding. His father, George, was a former slave who earned a living as a sharecropper. Like his 16 elder siblings, the young Jimmy was tasked in his early years with helping on the family farm.

At the age of 15, he left home to find work at one of the area’s many stables. He was doubtlessly inspired by the success of the talented African American jockeys and trainers who dominated the sport of horse racing during this era, despite the widespread racial inequality that persisted in the country at large and particularly in the Southern States.

The aspiring teenage jockey’s big break came in August 1898 when he was given the chance to ride a horse named Jockey Joe at Chicago’s Hawthorne Racetrack. The race didn’t go well for Winkfield. He rode too aggressively for the liking of the stewards and received a one-year suspension. Yet a couple of stable owners recognized his potential and as soon as he was allowed to return to racing, he began to enjoy considerable success as a jockey.

Just two years after that disastrous first race, he rode in the Kentucky Derby for the first time, finishing a creditable third. During what proved to be a stellar year, Winkfield returned to Churchill Downs in 1901 and won his first Kentucky Derby. When he repeated the feat the following year, he became only the second jockey to win the race in successive years. Winkfield’s triumph in 1902 proved to be the last Kentucky Derby win for an African American jockey. For all their previous domination, African Americans were now leaving the sport in droves, as they struggled to find rides because of heightened racial prejudice.

Despite his reputation as one of the greatest jockeys of his generation, even the talented Winkfield eventually fell foul of the predominantly white horseracing fraternity. His fall from grace was additionally exacerbated by a spectacular fall-out with one of the sport’s most powerful figures.

Churchill Downs, 1902

Photo Credit: WikipediaHaving finished second in the 1903 Kentucky Derby, Winkfield agreed to ride one of John Madden’s horses in the Futurity Stakes, a prestigious New York race with a huge prize pot, only to renege on the deal at the last minute so that he could ride instead for a rival owner. The influential Madden was reportedly so enraged by Winkfield’s actions that he vowed to end the jockey’s domestic racing career by persuading other leading owners not to employ him. Madden’s campaign proved so successful that Winkfield, who was still only in his early twenties, soon found himself largely ostracized from the sport.

The beleaguered jockey received an unexpected lifeline when he was offered the chance to race in Russia. He seized this golden opportunity with both hands. The record books show that over the following decade he won many of the most prestigious races in Eastern Europe on multiple occasions including the Russian Derby, the Russian Oaks and the Warsaw Derby.

Now at the peak of his career, he rode for wealthy Russian oligarchs, millionaire oil tycoons and European nobility. As a result, he was able to enjoy the kind of playboy lifestyle of which he could scarcely have even dreamt back in the old days in Kentucky. In a later interview, Winkfield revealed how he lived in a luxurious penthouse suite at Moscow’s five-star National Hotel, eating caviar for breakfast and even employing his own Russian valet. “I was at the top of the tree”, recalled the legendary jockey.

National Hotel, 1904

Photo Credit: WikipediaAll that changed when the Bolsheviks seized power in 1917. Escaping the revolution, Winkfield followed the Moscow Jockey Club to its new base in the Black Sea resort of Odessa, about 700 miles south of the Russian capital. He competed in races there for around two more years until one morning, in April 1919, he was greeted by the sound of cannon fire. The Bolsheviks had reached the outskirts of the city, meaning that it was time to flee again.

Winkfield joined a pre-arranged escape party led by a Polish nobleman, named Frederick Jurjevich, which involved the mass evacuation of not just men, women and children but also more than 200 of the world’s finest thoroughbred horses. Together, they set out on a hazardous journey to the Romanian capital of Bucharest where the women and children were put on trains bound for Poland. The men and surviving horses continued onwards with a perilous 600-mile trek across the inhospitable terrain of the Transylvanian Alps, finally making it to Warsaw, according to Winkfield, “exhausted and dead broke” some three months after leaving Odessa.

The American was now approaching middle age, but he remained in demand as a jockey, and he was soon heading for Paris where one of his former wealthy Russian clients had established a new stable. Winkfield prospered in the French capital, both professionally and financially, and became a notable celebrity on the Parisian social scene where he associated with the likes of Paul Robeson and Josephine Baker.

In 1922, he married Lydia de Minkiwitz, the daughter of a wealthy expatriate Russian aristocrat. His new father-in-law presented the couple with a two-acre estate in the affluent suburb of Maisons-Laffitte. Here Winkfield had plenty of room to establish a small racing stable of his own. Following his retirement from riding in 1930, he achieved some notable success as a trainer until the Nazi invasion of France in 1940 meant that he was once more compelled to flee his home.

After an absence of many years, Winkfield returned to the States, along with his wife and two children, Liliane and Robert. The African American discovered a country still deeply divided by racial inequality. His achievements in the saddle at the Kentucky Derby were now a distant memory, conveniently long forgotten by most, whilst news of his remarkable success as a jockey and trainer in Europe had seemingly not reached American shores.

Having been forced to hand over his lucrative racing business back home in Paris to the Nazis, Winkfield was now reduced to finding work in the States as a humble stable hand. He later recalled a conversation that occurred when he was working for a prominent owner and trainer of the era named Pete Bostwick. On recognizing his name as a former Derby winning jockey, Bostwick asked him what he had been doing all these years. “Well, I tell you, Mr Bostwick, I been around”, replied Winkfield with typically laconic humor.

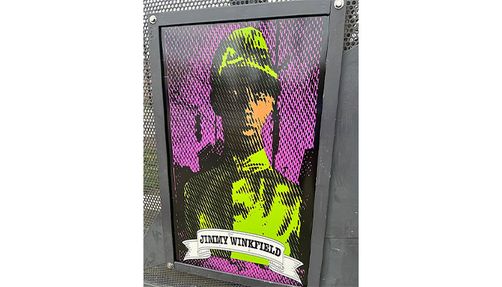

Art installation in Lexington, KY

Photo Credit: WikipediaBy the end of World War II, Winkfield was beginning to find his feet again and found work as a trainer for a handful of owners, including Bostwick. He was even able to purchase a few horses of his own but found it impossible to replicate the success he had enjoyed in pre-war Paris. The Winkfield family eventually decided to return to Maisons-Laffitte with a view to resurrecting their former stables. With the support of his son, Robert, Winkfield proved typically adept at reviving the family’s fortunes. Only a couple of years after returning to France in 1953, the Winkfields are reported to have had 36 horses in training at Maisons-Laffitte.

Winkfield rarely returned to the United States thereafter and his final visit, in 1961, was marred by an infamous incident. The former jockey had been invited to attend that year’s Derby and, ahead of his first visit to Churchill Downs in nearly six decades, Sports Illustrated organized a reception to celebrate his extraordinary career at the prestigious Brown Hotel in Louisville. Accompanied by his daughter, Liliane, the 79-year-old arrived at the front door to be told that he couldn’t enter there because of the hotel’s racial segregation policy. The evening’s honored guest was only finally granted admission when the event’s organizers intervened on his behalf.

He never visited the States again and died, aged 91, in March 1974, at his adopted home in France. Three decades later, Liliane witnessed her late father finally receive official recognition of his remarkable achievements when he was inducted into the U.S. Racing Hall of Fame in a 2004 ceremony.