In May of 1845, an expedition led by Captain Sir John Franklin set out from England to explore the Arctic. Franklin guided two ships—HMS Erebus and HMS Terror—through unnavigated sections of the Canadian Arctic's Northwest Passage. The goal was to chart magnetic data to gain a better understanding of nautical navigation. However, this highly publicized journey was met with disaster rather than success.

In September of 1846, Franklin and his crew of 129 officers and men became icebound in Victoria Strait near King William Island. After being trapped in the ice for over a year, Franklin's ships were eventually abandoned in the spring of 1848. By this time, Franklin and roughly two dozen others had perished. The remaining survivors were led by Francis Crozier, Franklin's second-in-command, and James Fitzjames, the captain of Erebus. The men journeyed on toward the Canadian mainland before ultimately disappearing, along with any trace of the ships.

Related: 7 Books About Disastrous Shipwrecks in History

After facing significant pressure from the public, especially Franklin's wife, Jane, the Admiralty sent out a search for the missing expedition in 1848. This first fruitless search would not be the last. Despite numerous subsequent search parties, only a handful of relics and the remains of two men returned to British soil over the next century and a half. The wreck of Erebus wasn't discovered until 2014, and the wreckage of Terror was located in 2016.

Much of what we know about the fatal expedition comes from archaeological evidence and interviews with local Inuit people. Looking back on the tragedy, we now know that death didn't come easy to the men of Franklin's expedition. Scientists theorize many fell victim to hypothermia, starvation, lead poisoning, scurvy, and more unfortunate side effects of a hostile Arctic environment. Marks on some of the recovered bones might also suggest instances of cannibalism.

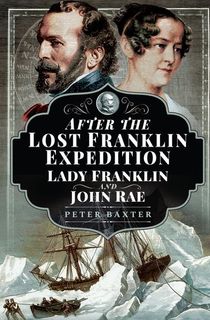

But what of the events surrounding this disastrous Victorian-era polar expedition? What brought the crew to this dangerous and near-impossible journey, and what became of those they left behind? Author Peter Baxter aims to shed light on this enigmatic voyage in his book After the Lost Franklin Expedition.

Beyond giving readers insight into the epic expedition, Baxter takes a look at Lady Franklin, who, as an uncommonly well-educated and independent woman of her time, was determined to protect her husband's legacy. The book also follows John Rae, the explorer whose investigation into the lost expedition's fate sparked a vicious dispute with Franklin's widow.

In this excerpt from After the Lost Franklin Expedition, Baxter takes readers behind the scenes of the initial concern growing back in England, after two years had gone by without word of the ships or the men onboard.

Read an excerpt from After the Lost Franklin Expedition below, then download the book.

The year was 1847, and Franklin had been absent from British shores for over two years. He would, if he was alive, be settling into his second winter in the Arctic. Not a word had been heard from him since his departure from the Orkneys, and the metropolitan capital of the empire was alive with speculation.

Rae knew that Richardson and Franklin were friends, and he could quite understand why Richardson was driven to mount a search. He could hardly have known, however, at least not then, that it had been Richardson who had written that letter, confirming Franklin’s physical and mental fitness, which now sat heavy on his conscience. He had done it rather reluctantly, it must be said, after Jane Franklin had implored him to do it. There was, therefore, complicity between the two of them, in a plot that once seemed so intuitive, and so magnificent, but which now seemed a little shabby and irresponsible. And, of course, it was that noble fool, that wonderful old Franklin, who was bearing the consequences.

Jane, only recently returned to London from a long constitutional in Madeira, received Richardson’s letter with the same anxious hope that she did every other word or speculation on the fate of her husband. The Arctic Committee, that informal club of polar experts, who kept Jane Franklin rather like a mascot, were apt to assure her that her anxiety was premature. Yes indeed, the missing expedition was settling into its second Arctic winter, but it was equipped and supplied to do so, and in fact, the Erebus and Terror could conceivably spend a third and fourth winter in the Arctic before any real concern need be felt.

Related: This Is What It Was Like To Be Marooned In The Age Of Sail

And it was all true, the two ships were indeed the best equipped so far for such an expedition, and they certainly were supplied for several years. Jane was warmly reassured by those who ought to know that Sir John would almost certainly sail out of the Beaufort Sea, and through the Bering Strait sometime in the summer of 1848. Jane, of course, was impatient of all of these platitudes. She could not shake off a lingering sense of foreboding, and so she gradually began to leverage her own money, contacts and influence to get a search off the ground.

One of these contacts was a 38-year-old Scottish whaling captain by the name of William Penny. Penny is an intriguing character, and although there is no clear record of when or how he and Jane met, he was one of those hardy, intellectual and accomplished men that she seemed, in her mature years, to find so fascinating. Since the age of 12, Penny had followed the annual whaling fleet through the Davis Strait, and into the prime whaling waters of Baffin Bay. By his late thirties, he was probably one of the best known of a breed of tough Arctic navigators, seasoned by the demands of commercial trade and unsupported by Royal Navy resources.

Jane put it to him that a reward of £3,000 was on the table for any whaling crew working through the 1847 season who returned word on Sir John, and even for those that made an excellent effort. Such a sum of money, substantial in the context of the times, was not really quite enough to divert a commercial whaling expedition off course on the mere possibility of a sighting, so it did not provoke a great response. Penny himself, however, was moved by Jane’s evident distress, and during the following season he entered Lancaster Sound, but he too was stopped by ice and did not on that occasion search much further.

A cash reward of £3,000, however, did get people talking. Parlour conversation in London began to dwell in admiration on the pluck of a spirited Victorian woman. It was all very admirable, but it was not the stuff of a real, concentrated search effort that only the government could mount. Jane, in any case, was not, at that point, calling for such a thing. To do so would have been both presumptuous and premature. There was, however, one anti-establishment voice – a very shrill and unpopular voice – which was steadily raised in a call to action.

Doctor Richard King was an avid and prolific composer of letters to the press, and many more to various government officials and agencies, pressing year after year his yearning to mount another expedition. This time, however, he made a very salient point.

Related: Lost at Sea: What Happened to the Mary Celeste?

King’s efforts at this crucial juncture are interesting, and in terms of Franklin scholarship, also important. Obviously he nurtured a deep grievance against the naval establishment for its refusal, time and again, to acknowledge his virtuosity, and grant him an expedition. He also, at the same time, railed against the informal network of polar explorers who just would not admit him into their circle. Despite his infuriating volubility, however, and even though he had barely set foot on the Arctic Archipelago, he had a keen and educated understanding of its complex geography. It was he who was the first to warn a complacent establishment that the Franklin Expedition was likely in trouble, and it was he who began suggesting possible coordinates. His very best intentions, however, were often eclipsed by the fact that he was such a disagreeable character, and had so alienated that very establishment that it took no more than his endorsement of a theory for it to be roundly discredited.

On 10 June 1847, King composed a long and detailed letter to Lord Grey, Secretary of State for the Colonies, the opening paragraph of which reads thus:

My Lord, – One hundred and thirty-eight men are at this moment in imminent danger of perishing from famine. Sir John Franklin’s Expedition to the North Pole in 1845, as far as we know, has never been heard of from the moment it sailed.

The letter was necessarily long and exhaustive in detail and would be tedious in the extreme to reproduce here. It is, however, impossible to read through it without being struck by its fundamental wisdom and accuracy, despite language sure to set the teeth of the officer forced to read it on edge. King clearly had no powers of tact or diplomacy, and indeed no control over his pen, but he knew what he was talking about.

1845 photograph of Sir John Franklin.

Photo Credit: Wikimedia CommonsIt was a tremendous shame, King reflected, that Lord Stanley, Secretary of State for the Colonies at the time of Franklin’s departure, had seen fit to reject King’s own offer to lead an overland expedition to the same region, to complement and support that of Franklin’s. If he had not, and if King would be at that very moment in the Arctic, then the two expeditions could hardly have missed one another, and none of the present anxiety would be felt. In fact, there happened to be little official anxiety, and King’s latest letter was treated in much the same way as the many that had preceded it. An anodyne reply was offered, if indeed, any reply at all, after which it was filed away and forgotten.

King, however, offered his opinion anyway, even if no one would listen to it. Bearing in mind the official orders issued to Sir John, he believed that the Franklin Expedition was at that moment locked in ice somewhere to the west of North Somerset Island, north of the Boothia Peninsula in Barrow Strait. He further warned that if Sir John Franklin and his crew were to be rescued at all, an expedition would need to be mounted in the summer of 1849 by the latest. Beyond that point, the odds of survival would begin to wither. And if a search and rescue expedition was to reach the stranded mariners before then, planning for it must start immediately. He was as available as always to lead the land portion of that expedition, and would Sir John emerge in the Beaumont Sea in the summer of 1848, as expected, what would have been lost by the provision of sending out a search expedition?

Related: These Recently Unearthed Coins May Have Solved a 17th-Century Mystery

This was an earnest and intelligent appeal, but unfortunately also issued in the same language that King was so susceptible to, and if it was taken seriously anywhere at all, it was done so without acknowledgement.

Number 21 Bedford Place, however, was one such place. Although she would make no mention of the fact to her friends in the exploration community, Jane was listening very carefully to Doctor King’s prognostications. She also was busy educating herself on the route and technicalities of the lost expedition, on polar geography in general and the tendencies of seasonal ice. Having acquired and read the official orders of Sir John’s expedition, she was beginning to understand its objectives, and its likely course and direction. She found herself in agreement with King, although she took her ideas not to him, but to Sir John Richardson.

Jane found the old birdwatcher and flower-presser on holiday on the South Downs, and there she urged him to somehow get the Admiralty thinking about a rescue. Richardson did indeed approach the Admiralty, and perhaps a little to his surprise, he was given a reasonably free ticket to begin planning an overland search. With that in mind, he went home and gave the matter a great deal of thought. When Jane was informed a day or two later, she was giddy with delight, and Miss Sophia Cracroft, who was by then Jane’s constant companion, was also seen to smile.

Very quickly thereafter, the fact became public knowledge. Sir John Richardson, the venerable expeditioner of yore, would journey forth to Canada to find his missing friend. It was the stuff of newspaper copy. Memories of the ‘Man Who Ate his Boots’ were revived, and older persons found themselves remembering that episode. The imagination of the nation was stirred, and the question of the lost Franklin Expedition became suddenly sentimental. Lady Jane Franklin was portrayed as the lonely Penelope, awaiting her lost Odysseus, pleading with his esteemed friend to find him. It was sensational. There were a few letters to the press, and then more, some beginning to question an unfeeling Admiralty, and a hidebound government, both so indifferent to its lost heroes.

In the meanwhile, when he heard the news, Doctor Richard King could hardly believe his ears. He was just 36 years old, in the prime of his life, and had himself submitted an application to do precisely this. And yet, suddenly, Sir John Richardson, the ageing expeditioner of an earlier era, was advancing plans for an expedition up a river and to the coast to search the Arctic Archipelago. An enfilade of verbiage was unleashed by King, mainly by way of letters to the press, and the point that he made was not unreasonable. Sir John Richardson was going back to the Arctic when he would rather have done anything else, and King was staying home when he so badly wanted to go.

Related: The Strange and Tragic Shipwreck of the Morro Castle

These, however, were Doctor King’s questions, and they are worth repeating. In the first place, he tried forcefully to make the point that the lost expedition would not be bearing down on the mouth of the Mackenzie River, where Richardson was now proposing that the search begin. It was too far west. He again pointed to Barrow Strait and North Somerset Island, pleading that an expedition proceed not up the Mackenzie River, but his own preferred watershed, the Great Fish River. Even the simplest fool, he said, could deduce that any party of desperate men searching for relief from ice, snow and starvation would not head west, but south, towards the mouth of the Great Fish River. He wrote:

To the western land of North Somerset … where, I maintain, Sir John Franklin will be found, the Great Fish River is the direct and only route; and although the approach to it is through a country too poor and too difficult of access to admit of the transport of provision, it may be made the medium of communication between the lost expedition and the civilised world.

He made this point time and again, and he did it because it was so thoroughly ignored. Who was he after all? One expedition over a decade old, and he distinguished himself then only in objecting to the findings and accounts of the leaders of the expedition. Never since had he set foot in the Arctic. History, and numerous historians, have referred to Richard King as the Arctic ‘Cassandra’, doomed to prophesy the truth that no one would hear. He seemed endlessly to cry, and yet no one would listen.

Want to keep reading? Download After the Lost Franklin Expedition.

Franklin's expedition into the Canadian Arctic is an infamous part of history. Unfortunately, the odds were stacked against this polar exploration from the start. The Northwest Passage would not be successfully navigated until 1906, when Roald Amundsen accomplished the task aboard the Gjøa.

In addition to the gruesome and tragic demise of Franklin and his men, the consequences of this 19th century journey would reverberate throughout Britain. Peter Baxter's book explores not only the expedition itself, but the interpersonal repercussions that followed, the political machinations behind subsequent search parties, and the media frenzy that accompanied the tragedy. Download After the Lost Franklin Expedition today for a detailed look into the epic polar voyage and the events that followed.

This post is sponsored by Open Road Media. Thank you for supporting our partners, who make it possible for The Archive to continue publishing the history stories you love.