WWII fanatic or not, you very likely are familiar with D-Day. The event’s actual codename was Operation Neptune, the assault aspect of a larger operation coined Operation Overlord—but it is more commonly referred to as D-Day than Operation Neptune. That being said, the term D-Day is not specific to WWII, and not even to this particular day; “D-Day” is a general term for any military operation’s start date. In fact, there were multiple D-Days during WWII.

However, none are quite as well known as the D-Day that began on June 6, 1944. On this day, Allied forces combined their land, air, and sea forces to invade the beaches of Normandy, France. The operation was the largest seaborne invasion in military history. General Eisenhower and others were convinced that D-Day would be the operation that ended the war. While it didn’t abruptly end German ambitions in Europe right then and there, the invasion’s military success opened Europe to the Allies, and Germany surrendered on May 7, 1945, less than a year later.

Of the many interesting aspects about this operation, one is less commonly known: the all-Black battalion whose contributions were so crucial that we couldn’t have won without them, and how the injustices they experienced in WWII were a catalyst for the start of the Civil Rights Movement.

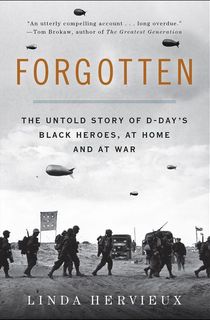

In Linda Hervieux’s Forgotten, we get to read about the 320th Barrage Balloon Battalion, which was a unit of African American soldiers who landed on Normandy on D-Day, tasked with manning a curtain of armed balloons to defend against enemy aircraft. Though a member of the Battalion was deservedly nominated for the Medal of Honor, Jim Crow America wouldn’t bestow it upon him, as Black soldiers could not be recipients of this honor during WWII.

Using newly discovered military records and original interviews with surviving members of the 320th and their families, Hervieux tells the story of their wrongfully overlooked yet extraordinary mission. She highlights the cruel juxtaposition between American racial politics at home versus serving in abroad.

Read an excerpt from Linda Hervieux’s Forgotten below to deepen your knowledge of WWII, and then download the book today.

On a sunny morning in April 1943, Wilson Monk and three friends left Henry County behind and boarded a train bound for Memphis, the city on the Mississippi River where Cab Calloway, Louis Armstrong, and Muddy Waters were regulars in the Southside clubs. Black musicians were doing astounding things on Beale Street, cradle of the blues and incubator for the sultry soul that would come to be known as the Memphis sound. Memphis sure beat sleepy little Paris, the closest city to Camp Tyson. In Paris, a single USO club—the one for Negroes—was the only option for the thousands of black soldiers needing to blow off steam. If they wanted a drink, and they usually did, they were out of luck: Henry Country was dry. On Beale Street, the liquor flowed as smooth and easy as the music. In April 1943 you could catch Amateur Night at the Palace Theater, or see the beautiful Lena Horne in Cabin in the Sky at one of the ten movie houses—out of forty—that admitted Negroes.

With weekend passes in hand, the Tyson men settled in for the three-hour ride, content to trade balloons, nocturnal hikes, and mess hall eats for some blues, barbecue, and a bourbon or two. What they found was a city where black men were not welcome in most places. Their first stop was a diner near the station, where someone suggested they play some songs on the jukebox. Monk placed a fifty-cent piece on the counter and asked the man on other side for change. The man glared back, opened the cash register, and threw a handful of nickels back at him. “If you wasn’t in uniform,” the man said, “you wouldn’t get a damn thing from me.”

Later that day, the Tyson men watched, incredulous, as a long line of German prisoners of war filed into a restaurant where black men were not welcome. The enemy can eat there but we can’t. It was an often-repeated scene: African Americans were turned away at restaurants throughout the South, and sometimes in the North, but German and Italian POWs were welcome because they were white. During the war years, 425,000 Axis prisoners were interned in the United States, some 800 of them at the Memphis Army Depot.

Many of the POWs were vocal in their preference for life in America over fighting on the front lines, and their enthusiasm and compliance granted them liberties. They worked for pay at jobs, often on farms across the Midwest and the South, where most of the six hundred POW camps were situated. Their privileges, often far and above what was required by the provisions of the Geneva Convention, drew the wrath of not only black soldiers but also some whites, who considered the prisoners’ lives far too cushy. Some camps earned the moniker the “Fritz Ritz.” At Camp Claiborne, Louisiana, German POWs could move about freely and use the same facilities as white soldiers. They got passes into town—a privilege denied to black troops, who were confined to barracks built on swampland in the worst part of the sprawling base.

Black soldiers seethed as German prisoners shared cigarettes and jokes with the white soldiers guarding them and struck up conversations with the locals. Many of these encounters occurred at transit points, where black soldiers were decidedly not welcome, but where enemy troops could grab a bite before boarding their next train—in whites-only cars. A soldier named Davis Cason Jr. recounted how he found a meal in “a dingy, dinky place” near the train station in El Paso, Texas, after bypassing the bustling station restaurant where “there sat the so-called enemy comfortably seated, laughing, talking, making friends, with the waitress at their beck and call. If I had tried to enter the dining room, the ever-present MPs [military police] would have busted my skull.” Elsewhere in Texas, Tech. Sgt. Richard Carter was sickened when he spotted “American MPs and some of Hitler’s bully boys . . . having a ball together, wining and dining” in the train station restaurant. Carter had just been roused from a nap on a station bench in withering heat. A “typical southern cracker cop” had rapped the soles of his shoes with a billy club and hollered, “You niggahs can’t sleep in heah,” Carter said, imitating the cop’s country drawl.

The largest court-martial of the war sprang from accusations that resentful black soldiers at Camp Lawton in Seattle had attacked Italian POWs, killing one by hanging him from a tree and wounding many others. In 2008 the army threw out the convictions, citing a cover-up and a trial that was “fundamentally unfair” to the soldiers, who were denied access to records and their lawyers.

Seven decades after the war, memories of POW privileges still touched a nerve with black veterans. “It really hurt us,” said Wilson Monk, shaking his head at the memory of the cordial, if not outright back-slapping, treatment afforded many German prisoners. Monk was hardly naive; he expected this kind of treatment in the South. Even his northern hometown was a hardly a bastion of racial equality. Burned in Monk’s soul was the day when, as a boy, he had watched as the Ku Klux Klan paraded in full white pointy-hooded regalia along West Park Avenue in Pleasantville, New Jersey, past his family’s home, and set fire to a cross in a field down the street. Still, the treatment in Memphis stung. Maybe it was because he was now a soldier enlisted in the fight for freedom and democracy.

Monk didn’t know it at the time, but he was lucky his uniform had at least gotten him change for the jukebox. For many soldiers, their army khakis marked them as a target. Tensions had been high across the South for many months as thousands of black recruits poured into army bases built to take advantage of year-round training in temperate weather. Southerners loudly protested the influx of so many Negroes, and the Southern Governors Conference of 1942 unanimously objected to their presence, with the Alabama chief executive calling it a “grave mistake.” Northern black soldiers were dragged off buses for refusing to sit in the back, and any white soldiers who took their side were threatened by drivers, who often carried guns. When a private at Camp Claiborne objected to being called “nigger,” the train conductor who used the slur shouted, “Yes, you are a nigger, a goddamn nigger. You are down below the Mason-Dixon Line and you are all nigger boys down here.” Simply walking the streets was fraught with indignities, and even ceding a place on the sidewalk for a white person wasn’t always enough. A white woman in Alabama spat on Lt. Earl Kennedy, he said, “for having my black skin in an officer’s uniform.”

In one of the army’s most outrageous Jim Crow episodes, an order came down at a Pennsylvania camp warning that “any association between the colored soldiers and white women, whether voluntary or not, would be considered rape. And the penalty would be death.” After howls of protest from William H. Hastie, the civilian aide to the war secretary, and the NAACP, the War Department revoked the order.

White antipathy toward black soldiers had existed as long as there had been black soldiers. From the Revolutionary War onward, many whites opposed arming Negroes. During the First World War, white southerners reacted with outrage and violence when Negroes reported for duty, their uniforms seen as an implicit demand for respect. When two thousand black troops from New York arrived in Spartanburg, South Carolina, in October 1917, the authorities warned that there would be trouble. The sight of so many black men in uniform “with their northern ideas about racial equality” was “like waving a red flag in the face of a bull,” the mayor told the New York Times. Their white commander understood that the simple act of his men standing at attention “chest out, shoulders back, chin up—a pose of strength, dignity and pride—would likely offend the southern Jim Crow mentality,” writes historian Peter Nelson. Mounting hostility eventually prompted the War Department to send the black troops to France, where the New York 369th Infantry Regiment found glory as the Harlem Hellfighters.

During the so-called Red Summer of 1919, race riots flared in some thirty cities from New York to Knoxville, leaving thousands dead, black and white. At that time, it marked the greatest period of racial strife the nation had ever seen. “Mobs took over cities for days at a time, flogging, burning, shooting and torturing at will,” wrote historian C. Vann Woodward. “When the Negroes showed a new disposition to fight and defend themselves, violence increased.”

The primary provocation for the violence was the return of white soldiers, who reclaimed jobs taken by blacks who had migrated North in their absence. For their part, black soldiers who had tasted equality in France were no longer prepared to tolerate discrimination and limited work opportunities. Many black vets saw themselves in the Eddie Cantor song “How Ya Gonna Keep ’Em Down on the Farm (after They’ve Seen Paree”). Soldiers were allowed to wear their uniforms for up to three months after being discharged, and many black veterans did so. For some, it was a show of pride in their service. Others were too poor to afford new clothes. In 1919, seventy-seven black men were lynched, at least ten of them veterans in uniform. Two were burned alive.

Southern whites sometimes lay in wait for returning soldiers at railroad stations and ripped off their uniforms. Law enforcement officials often took part in the attacks, and even when they didn’t, their silence provided official sanction. A sore point among whites was news that Negroes serving abroad were treated well by European whites. Stories had filtered home about the warm welcome the French accorded to black soldiers, of salutes and, worst of all, romances with white women. Mississippi senator James K. Vardaman called for vigilantes to keep watch over “those military, French-women-ruined Negro soldiers.”

The police chief in Sylvester, Georgia, blamed “a bitter feeling against colored soldiers” for one breathtaking act of violence committed against a black veteran in uniform. Daniel Mack had refused to yield his place on a Georgia sidewalk to a white man in April 1919 and was thrown in jail for two days. At his arraignment, he caused further outrage by declaring, “I fought for you in France to make the world safe for democracy. . . . I’ve got as much right as anybody else to walk on the sidewalk.” He got a dressing-down by the judge, who told him, “This is a white man’s country and don’t you forget it.” Before he could serve out his sentence of thirty days’ hard labor, a mob dragged him from his jail cell, beat him, and left him for dead. Mack somehow survived.

Two decades later, a black man still invited violence when he donned an army uniform. In April 1941, a black soldier was found hanging from a tree at Fort Benning, Georgia, his hands tied behind his back. Base officials at first called the death a suicide. Nobody was ever charged. Billie Holiday evoked the macabre world of lynching each time she performed the haunting “Strange Fruit,” her best-selling record that recalled a double lynching of two black men:

Southern trees bear a strange fruit,

Blood on the leaves and blood at the root,

Black bodies swinging in the southern breeze,

Strange fruit hanging from the poplar trees.

Pastoral scene of the gallant south,

The bulging eyes and the twisted mouth,

Scent of magnolia sweet and fresh,

And the sudden smell of burning flesh.

In the fall of 1941, William Hastie unsuccessfully urged his boss, the war secretary, to speak out against the rising incidents of violence directed at black soldiers, including the killing of black troops at Fort Bragg, North Carolina, and the shooting of black soldiers at Fort Jackson, South Carolina. “Day by day, the negro soldier faces abuse and humiliation,” Hastie later wrote. “In such a climate resentments, hatreds and fears and misunderstandings mount until they erupt in sensational violence.”

Life in northern camps often wasn’t much better. Racial clashes flared repeatedly at Fort Dix, New Jersey, an embarkation point for troops heading overseas that doubled as a reception point for inductees. Northern black draftees were shocked by their first taste of life alongside southern troops “and their use of a well-known epithet to describe all people darker than they are,” the Afro-American newspaper reported. The slights were many, and often petty, such as black soldiers being barred from the PX except during certain hours. “We might as well have been in the heart of Dixie,” one of them said.

The mounting wave of discontent culminated in a riot that broke out off base in April 1942 as black and white soldiers queued outside Waldron’s Sports Palace. What happened next is unclear. In one version, a black soldier wanting to use a telephone took offense when a white MP told him he couldn’t leave the line. In the ensuing violence, some fifty shots were fired and three soldiers lay dead, two black privates and one white MP. The post’s public relations officer later explained opaquely that the melee was triggered by “some persons with a little too much race consciousness getting off track.” The situation remained unchanged one year later, when the Afro-American reported that the base was still a “veritable powder keg.” The incidents certainly belied the findings of a 1942 report by the Army General Staff that concluded that the policy of segregation had “practically eliminated the colored problem, as such, within the Army.”

Even when violence wasn’t an issue, northern communities sometimes opposed the arrival of black soldiers, even in places where there was already a sizable African American population. A base for a black Army Air Forces tactical unit failed to find a home after vehement protests from officials in Syracuse, New York; Columbus, Ohio; and Windsor Locks, Connecticut. Yet for the black soldier, the South remained the center of strife and rage. “The South was more vigorously engaged in fighting the Civil War than in training soldiers to resist Hitler,” said Grant Reynolds, who made the remark about his first posting at Camp Lee, Virginia. He later resigned as chaplain at Fort Huachuca, Arizona, in protest of the racism he experienced there.