Despite its history as a royal residence, armory, and house of jewels, the Tower of London is often associated with incarceration, torture, and gruesome beheadings. However, this was not always the case—in fact, the building didn't become a formal prison until the Tudor period, which lasted from 1485 to 1603. It was during this time that infamous “traitors” like Anne Boleyn and Walter Raleigh spent their final days within the Tower's walls, only to meet very public deaths on the lawn or overlooking hill.

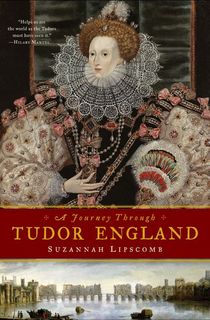

Suzannah Lipscomb's A Journey Through Tudor England offers an in-depth look at the period’s most famous locations and customs—including this particular part of the Tower’s history. Over one hundred inmates died upon the scaffold, but—as Lipscomb notes in the following excerpt—they didn't go without leaving pieces of themselves behind.

Read an excerpt from Suzannah Lipscomb's A Journey Through Tudor England, and then download the book.

The Tower of London is one of the most famous buildings in the world. With William the Conqueror’s eleventh-century White Tower at its centre and its many other towers largely completed in the reign of Edward I (1272—1307), it has been a fortress and a royal palace, and even, in the thirteenth century, housed a menagerie of exotic animals, including an elephant and a polar bear that fished in the Thames. It is famous for its ravens, the Crown Jewels, the Yeoman Warders (known universally as ‘Beefeaters’) and the fabled murder of the young ‘Princes in the Tower’, whose bones were found two centuries after their deaths. Henry VIII was the last monarch to invest in repairing and refurbishing the Tower, and all the Tudor monarchs processed from the Tower to Westminster for their coronations.

The Tower’s chief distinction in the Tudor period was, however, as a place of imprisonment and execution. Many Tudor prisoners would have arrived by boat and entered through the water gate in St Thomas’s Tower, now commonly known as Traitors’ Gate, which was reached from a tunnel under the wharf from the Thames. Compared to many Tudor prisons, the Tower was relatively comfortable. That it may also have been terribly boring is attested to by the extraordinary graffiti left by Tudor prisoners. Most of it, like tagging in modern graffiti, shows a fixation with leaving a record of one’s name. In the Tower, however, prisoners had a much more compelling motive than today’s graffiti artists: they feared, many quite rightly, that they would only leave their imprisonment to die.

During the Tudor period, the Tower of London—which had been a royal residence—became an armory, munitions house, and prison.

Photo Credit: Wikimedia CommonsBeauchamp (pronounced ‘Beecham’) Tower has some beautifully inventive graffiti: Thomas Abel, chaplain to Katherine of Aragon, was imprisoned for refusing to accept the annulment of her marriage to Henry VIII, and depicted his surname with the letter ‘A’ on a bell; the Dudley brothers, imprisoned after their failed attempt to crown Lady Jane Grey queen, carved an elaborate rebus to the right of the fireplace with their coat of arms in a floral border, where each flower represents one of the Dudleys. Another supporter of Jane’s carved the simple word ‘IANE’, while Sir Philip Howard, Earl of Arundel [see ARUNDEL CASTLE] — one of the many Catholics imprisoned in the Tower in Elizabeth’s reign — spent his ten years of confinement carving the Latin phrase, ‘The more suffering for Christ in this world, The more glory for Christ in the next.’ In the Salt Tower, you can see the most incredible carving of an astrological sphere or clock and inscription by Hugh Draper, imprisoned on an accusation of sorcery in 1561. Here, too, are indications of Catholic faith: ‘Maria’ carved into the walls, and a bleeding foot to indicate the five wounds of Christ. Henry Walpole, a Jesuit priest, was imprisoned here in 1593 and inscribed the walls with the Latin names of St Paul and St Peter, and the four fathers of the Church. Walpole’s story also reminds us of why the Tower was so feared in the sixteenth century: it could be a place of torture.

Perhaps surprisingly, torture was relatively rare, as only the Privy Council could authorise it. Nevertheless, there were forty-eight sanctioned cases of torture between 1540 and 1640. The Lower Wakefield Tower has a display of the weapons of torture: usually the rack; contorting irons for the legs, wrists and neck; or the manacles, from which a prisoner was suspended from the hands or wrists. Walpole was hung from the manacles fourteen times, and had the middle finger of his right hand torn off, but still refused to inform on other English Catholics [for more on English Catholics, see HARVINGTON HALL]. Ralph Ithell, a Catholic priest whose engraving from 1586 can be seen in Broad Arrow Tower, was racked for plotting to overthrow Elizabeth I. Earlier in the century (and contrary to a woman’s normal exemption from torture), the Protestant Anne Askew, who was imprisoned in the Cradle Tower, had also been racked. After her trial of June 1546, and in the hope that she would denounce a number of noblewomen for sharing in the heresy of which she was accused, two royal councillors, Thomas Wriothesley and the devious Sir Richard Rich, even turned the rack themselves.

More famous prisoners include Sir Walter Ralegh, gaoled three times in the Bloody Tower (as the Garden Tower was renamed after the murder of the Princes); Sir Thomas More [see LINCOLN’S INN], Bishop John Fisher and the poet Sir Thomas Wyatt the Elder who was interned in the Bell Tower (sadly, not open to the public). Wyatt wrote of seeing those accused of adultery with Anne Boleyn executed on Tower Hill:

These bloody days have broken my heart …

The bell tower showed me such a sight

That in my head sticks day and night.

There did I learn out of a grate,

For all favour, glory, or might,

That yet circa regna tonat [thunder rolls around the throne of kings].

Unlike other prisoners executed on Tower Green, Anne Boleyn was killed with a sword, not an axe.

Photo Credit: Lisby/FlickrThe Tower was also a place of death. In 1536, Anne Boleyn was imprisoned in the Queen’s lodgings, which ran from the Lanthorn Tower up towards the White Tower: precisely where she had stayed before her coronation three years earlier. She was tried in the medieval Great Hall: you can see where this would have been as you emerge from the Wakefield Tower. Anne was one of only seven people in the Tower’s history to be executed on Tower Green and she was then buried under the altar in the chapel of St Peter ad Vincula (the parish church of the Tower). She was also the only one to be executed with a sword, rather than an axe.

Tower Green, within the Tower itself, was chosen over Tower Hill for private, secure executions of high-ranking individuals. Two other queens of England died in this way: Henry VIII’s fifth wife, Katherine Howard, and Lady Jane Grey. The other victims were Margaret Pole, Countess of Salisbury, formerly governess to Princess Mary, who was chased across the scaffold by her executioner — ‘a wretched and blundering youth … who literally hacked her head and shoulders to pieces in the most pitiful manner’; Jane Boleyn, Lady Rochford, who had abetted Katherine Howard in her adultery; and Robert Devereux, Earl of Essex for his uprising against Elizabeth I. The Devereux Tower still bears his name.

The others buried at St Peter ad Vincula were executed in public on Tower Hill, on what is now Trinity Square Gardens. They included Edward Stafford, Duke of Buckingham, in 1521 (see THORNBURY CASTLE); George Boleyn, Lord Rochford, Anne Boleyn’s brother, in 1536; Thomas Cromwell, Earl of Essex and Henry VIII’s first minister, in 1540; Edward Seymour, Duke of Somerset and Lord Protector in 1552; and Thomas Howard, Duke of Norfolk in 1572. All died on charges of treason.

Strangely, the place instantly recalled when thinking of the Tower — the iconic White Tower itself — is that least associated with captivity and execution. Today it houses the collections of the Royal Armouries, including Henry VIII’s armour. Look out for the exquisite horse armour made for Henry in 1515: beautifully engraved all over with foliage, Tudor roses and pomegranates, its skirt bears the intertwining initials H and K, for Henry and Katherine of Aragon. As it was made to measure, it also shows that in 1515 Henry had a chest of just thirty-six inches, in contrast to the enormous size of his field and tournament armour of 1540, which you can also see here. In 1540, when Henry VIII turned fifty years old, his chest had expanded to an obese fifty-seven inches.

The Tower, as a place of incarceration, death and final rest for many, is a must-see for the Tudor visitor. The passing of time alone accounts for the fact that a place characterised by suffering, cruelty and death is now experienced as beautiful and impressive by those of us who, unlike many of its residents, can choose to leave.

Want to keep reading? Download A Journey Through Tudor England by Suzannah Lipscomb.