Louis “Studs” Terkel, born May 16, 1912, was a writer, historian, actor, and broadcaster who left behind a powerful legacy upon his passing on October 31, 2008. At the age of eight, he moved to Chicago, where his parents ran a rooming house. It is there that Studs Terkel claims he had his first opportunity to experience meeting individuals from various backgrounds, which got him interested in studying people—the way they interacted with others, the causes they believed in, and the role they played within the world. Although he received a law degree in 1934, he decided that his real passion lay in media, where he would be able to use his charisma to get people to open up about their lives. He made a name for himself in radio and became well-known for hosting The Studs Terkel Program on WFMT Chicago, where he interviewed guests including Martin Luther King Jr., Bob Dylan and Dorothy Parker.

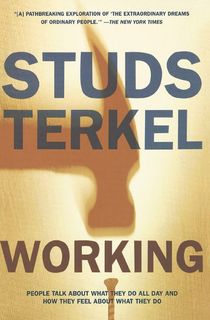

But in 1967, after having published his first book, Giants of Jazz (1956), he began writing various collections based on oral histories. These collections housed interviews centered around people’s feelings about living in the city; the accounts of the poor and rich during the Great Depression; and how WWII affected citizens’ everyday lives, for which he won the Pulitzer Prize. However, perhaps his most known and celebrated book is Working, his 1974 nonfiction account that offers a glimpse into the working lives of over 100 people and, most importantly, how they feel about the work they do.

Divided into nine “books” containing subsections broken into various themes, Terkel provides insight into a diverse range of jobs, from a garbage man to a photographer to a sex worker. All are given respect and dignity as Terkel allows them to voice their frustrations and joys about the work they either take pride in or profoundly hate. To read this National Book Award finalist and New York Times bestseller is “to hear America talking” (The Boston Globe).

Even though this book was published almost 50 years ago, it is still extremely timely as it explores what people find meaningful within their daily responsibilities while also highlighting the disparities between “higher-esteemed” jobs and less desirable occupations. It undoubtedly remains a valuable work that resonates with people of today, even inspiring Netflix’s 4-part documentary series, Working: What We Do All Day, hosted by Barack Obama and directed by Caroline Suh. Each episode follows three workers at the same socioeconomic level from lower-paying service jobs to “dream jobs” run by CEOs that are discussed within the context of the changes the American economy has undergone since Terkel’s time. Similarly to Terkel's collection, it captures the current mindset of people working to pay their bills while trying to figure out what ultimately brings them fulfillment.

For a sneak peek at Terkel’s powerful book, read the excerpt below from the perspective of a farm worker, then download Working today!

I began to see how everything was so wrong. When growers can have an intricate watering system to irrigate their crops but they can’t have running water inside the houses of workers. Veterinarians tend to the needs of domestic animals but they can’t have medical care for the workers. They can have land subsidies for the growers but they can’t have adequate unemployment compensation for the workers. They treat him like a farm implement. In fact, they treat their implements better and their domestic animals better. They have heat and insulated barns for the animals but the workers live in beat-up shacks with no heat at all.

Illness in the fields is 120 percent higher than the average rate for industry. It’s mostly back trouble, rheumatism and arthritis, because the damp weather and the cold. Stoop labor is very hard on a person. Tuberculosis is high. And now because of the pesticides, we have many respiratory diseases.

The University of California at Davis has government experiments with pesticides and chemicals. To get a bigger crop each year. They haven’t any regard as to what safety precautions are needed. In 1964 or ’65, an airplane was spraying these chemicals on the fields. Spraying rigs they’re called. Flying low, the wheels got tangled on the fence wire. The pilot got up, dusted himself off, and got a drink of water. He died of convulsions. The ambulance attendants got violently sick because of the pesticides he had on his person. A little girl was playing around a sprayer. She stuck her tongue on it. She died instantly.

These pesticides affect the farm worker through the lungs. He breathes it in. He gets no compensation. All they do is say he’s sick. They don’t investigate the cause.

There were times when I felt I couldn’t take it any more. It was 105 in the shade and I’d see endless rows of lettuce and I felt my back hurting . . . I felt the frustration of not being able to get out of the fields. I was getting ready to jump any foreman who looked at me cross-eyed. But until two years ago, my world was still very small.

I would read all these things in the papers about Cesar Chavez and I would denounce him because I still had that thing about becoming a first-class patriotic citizen. In Mexicali they would pass out leaflets and I would throw ’em away. I never participated. The grape boycott didn’t affect me much because I was in lettuce. It wasn’t until Chavez came to Salinas, where I was working in the fields, that I saw what a beautiful man he was. I went to this rally, I still intended to stay with the company. But something—I don’t know—I was close to the workers. They couldn’t speak English and wanted me to be their spokesman in favor of going on strike. I don’t know—I just got caught up with it all, the beautiful feeling of solidarity.

You’d see the people on the picket lines at four in the morning, at the camp fires, heating up beans and coffee and tortillas. It gave me a sense of belonging. These were my own people and they wanted change. I knew this is what I was looking for. I just didn’t know it before.

My mom had always wanted me to better myself. I wanted to better myself because of her. Now when the strikes started, I told her I was going to join the union and the whole movement. I told her I was going to work without pay. She said she was proud of me. (His eyes glisten. A long, long pause.) See, I told her I wanted to be with my people. If I were a company man, nobody would like me any more. I had to belong to somebody and this was it right here. She said, “I pushed you in your early years to try to better yourself and get a social position. But I see that’s not the answer. I know I’ll be proud of you.”

All kinds of people are farm workers, not just Chicanos. Filipinos started the strike. We have Puerto Ricans and Appalachians too, Arabs, some Japanese, some Chinese. At one time they used us against each other. But now they can’t and they’re scared, the growers.

They can organize conglomerates. Yet when we try organization to better our lives, they are afraid. Suffering people never dreamed it could be different. Cesar Chavez tells them this and they grasp the idea—and this is what scares the growers.

Now the machines are coming in. It takes skill to operate them. But anybody can be taught. We feel migrant workers should be given the chance. They got one for grapes. They got one for lettuce. They have cotton machines that took jobs away from thousands of farm workers. The people wind up in the ghettos of the city, their culture, their families, their unity destroyed.

We’re trying to stipulate it in our contract that the company will not use any machinery without the consent of the farm workers. So we can make sure the people being replaced by the machines will know how to operate the machines.

Working in the fields is not in itself a degrading job. It’s hard, but if you’re given regular hours, better pay, decent housing, unemployment and medical compensation, pension plans—we have a very relaxed way of living. But the growers don’t recognize us as persons. That’s the worst thing, the way they treat you. Like we have no brains. Now we see they have no brains. They have only a wallet in their head. The more you squeeze it, the more they cry out.

If we had proper compensation we wouldn’t have to be working seventeen hours a day and following the crops. We could stay in one area and it would give us roots. Being a migrant, it tears the family apart. You get in debt. You leave the area penniless. The children are the ones hurt the most. They go to school three months in one place and then on to another. No sooner do they make friends, they are uprooted again. Right here, your childhood is taken away. So when they grow up, they’re looking for this childhood they have lost.

If people could see—in the winter, ice on the fields. We’d be on our knees all day long. We’d build fires and warm up real fast and go back onto the ice. We’d be picking watermelons in 105 degrees all day long. When people have melons or cucumber or carrots or lettuce, they don’t know how they got on their table and the consequences to the people who picked it. If I had enough money, I would take busloads of people out to the fields and into the labor camps. Then they’d know how that fine salad got on their table.

Want to keep reading? Download Working by Studs Terkel today!

This post is sponsored by Open Road Media. Thank you for supporting our partners, who make it possible for The Archive to continue publishing the history stories you love.

Featured image: Dan Meyers / Unsplash