Willie Mays was one of the best baseball players of all time. An example of a “five-tool player”—that is, someone highly skilled in all major aspects of the sport—Mays began his career in the Negro Leagues before going on to play for the New York/San Francisco Giants and the Mets. While we won’t wax poetic about his extensive career achievements (you can read about them here), it must be pointed out that he was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1979, and was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2015 by Barack Obama—who has remarked, “It’s because of giants like Willie that someone like me could even think about running for president.”

Nicknamed the “Say Hey Kid,” Mays also developed a reputation for caring about his community, especially children, with whom he used to play pickup stickball games at home field. Staying closely affiliated with his teams even after retiring as a player, Mays died on June 18, 2024 at 93 years old.

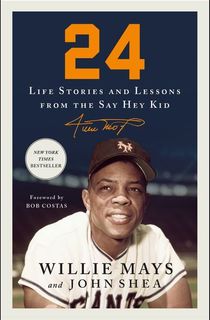

Mays published a book in 2020, a “mix of memoir, self-help, and baseball history” (Booklist) that will delight sports fans and give a fascinating glimpse into his extraordinary life. 24 (after his iconic jersey number) also delves into his positive personal philosophy. Read on for an exclusive sneak peek from the book, through which his legacy will live on.

Playing was the easy part. That’s what Willie did best. He appeared in 81 games through the rest of Trenton’s season and hit .353. The tough part was facing racism like never before, going from the comfort of an all-Black team with veterans looking out for him to being the only African American not only on the team but in the league.

Mays had always enjoyed and flourished being around teammates, but when he reported to segregated Hagerstown, Maryland, he suddenly found himself crosstown at an all-Black hotel, far removed from where the white players stayed. Hagerstown was a Braves affiliate and provided a rude welcome. It was the only team in the league below the Mason-Dixon Line, the traditional divide between the North and South, and the insults he heard each time he visited were impossible to forget.

They were calling me all the names you could imagine, pointing out my race. I remember from Piper (Davis) and all the guys in Birmingham, they said stay strong, ignore the name-calling, don’t play their game, which is what Jackie was told to do his first two years with the Dodgers. My dad said focus on baseball, not on what people are saying or thinking, rise above all that. It wasn’t easy.

I remember one series in Hagerstown, I got a lot of big hits the first two days. The final day, I was sitting in the dugout watching what the pitcher was throwing, trying to get a feel for what he had, when the announcer started calling out the names of the players. When he got to mine, he said, “Ladies and gentlemen. I know you don’t like this kid, but please stop hollering at him. He’s killing us.” I started laughing. I didn’t get a hit that day. I guess I relaxed so much I couldn’t hit the ball.

Trenton second baseman Harry “Ace” Bell said Mays was a target of insults in other cities, including Sunbury, Pennsylvania, where the Philadelphia A’s had a farm team. Many of these fans around the league hadn’t seen an African American play ball and were offended or even enraged by the notion of an integrated team. Mays turned heads with his elite performance and passion and began to soften some long-entrenched feelings of resistance and even hatred. Bell was impressed with how Willie rose above the abuse and focused on playing ball.

“Willie was such a nice kid,” Bell said. “He was friendly with everybody, and he would praise everybody. He’d be your best fan. And you could tell right away he could hit. There wasn’t anything that fooled Willie. I’m sure his Birmingham team had a better bunch of ballplayers than what Trenton had.”

Despite the segregated towns and treatment from racist fans, Mays looks back fondly at his Trenton team and can recite the entire starting lineup. He also recalls his first night in Hagerstown when he was across town alone, separated from the rest of the team. There was a sign of solidarity that he appreciated and has stuck with him.

Three teammates climbed through my window. They came in and slept on the floor until the morning. They were looking out for me. It was a nice gesture from those guys. I don’t think I needed help, but they wanted to help. You don’t forget that.

The Giants tried to make Mays feel more at ease when adding another minority player, José Fernández, but the experiment seemed forced and was short-lived. In large part, his teammates and manager, Chick Genovese, the brother of longtime Giants scout George Genovese, supported Mays and did what they could to make him feel comfortable.

“We had guys looking out for him, making sure he had a room and transportation,” said Bell, who joined the team about the same time as Mays, after graduating from college. “A lot of places wouldn’t accept a Black person. Wilmington, Hagerstown. He had to go to a different part of the town. Three or four of the kids volunteered to find a place for him in those cities. They made sure he had a room. It was always in the Black section. That’s how Willie lived when we were on the road. That’s the way it was at the time.”

As the second baseman, Bell saw plenty of Mays’ powerful arm. “I remember one of his first throws,” he said. “There was a guy tagging up at third to go home. Willie was in deep center field and threw the ball over the catcher’s head, if you can believe that. That’s the kind of gun he had. Marvelous arm. His throws were so easy to handle. He had a great arm, but his ball came in lightly. Some throws from people are heavy. His were always light, easy to handle. Right where you wanted it.”

Bell’s claim to fame that season—“when I tried to explain to people I was really a good ballplayer”—was he outhomered Mays five to four. Bell played just one more season and became a longtime baseball coach at Springfield High School in Pennsylvania, where he tutored future big-league catcher and manager Mike Scioscia. Mays had other aspirations and opened the 1951 season at Triple-A Minneapolis, the Giants’ top farm team.

Unlike in Trenton, Mays wasn’t the only African American. The Millers had third baseman Ray Dandridge, who was inducted into the Hall of Fame in 1987, and pitcher Dave Barnhill, but both were in their late thirties and never reached the majors. Mays, who credits Dandridge for guidance at an important time in his life and career, dominated American Association pitchers even more than he dominated Interstate League pitchers and lasted just 35 games for the Millers.

When the Giants signed me, I found it much easier playing in their minor-league system than playing in the Negro Leagues because the level in the Negro Leagues was so much higher.

Mays hit a whopping .477 with eight homers for the Millers and continued to impress everyone with his defense and speed. The time had come. Mays was headed to the majors. In a short period, Millers fans fell in love with Mays and were disappointed when he got the call, so much so that Giants owner Horace Stoneham felt compelled to take out an ad in the Minneapolis Tribune explaining the move: “Mays is entitled to his promotion, and the chance to prove that he can play major-league baseball. It would be most unfair to deprive him of the opportunity he earned with his play.”

I was in a movie house. We were on the way back to Minneapolis and were in Sioux City, Iowa, for an exhibition. During the movie, I see a message on the screen: WILLIE MAYS PLEASE REPORT TO THE LOBBY. I went out there, and the manager of the movie house told me to go back to the hotel. My manager, Tommy Heath, gave me the news. I talked to Leo (Durocher). I told him I liked it in Minneapolis and wanted to stay, but he wanted me in Philadelphia the next night with the Giants. I thought I could play with those guys. I didn’t go back to Minneapolis. I went straight to Philadelphia.

On May 24, 1951, the twenty-year-old Mays got the call that generations of deserving Negro Leaguers never got. Including Piper Davis, his manager in Birmingham. And Oscar Charleston, an all-around talent who was considered Mays before Mays. Josh Gibson, Cool Papa Bell, Buck Leonard, Smokey Joe Williams, Ray Dandridge. And many, many others. Mays was carrying the weight of countless players who were overlooked because of their skin color. He was going to play for Leo Durocher. He was going to join Monte Irvin and Hank Thompson, who became the Giants’ first two African Americans two years earlier. He was going to fulfill a dream that his father told him was possible after the Dodgers signed Robinson.

When I played in the Negro Leagues and then minor-league ball and then the Giants, my dad kept in contact. It seemed he called every night. “What are you doing?” I’d say, “What do you mean, what am I doing? I’m trying to play, man.” He also kept in touch with Piper and Leo and Monte. If my dad couldn’t be there with me, he made sure I was taken care of. He made sure I got in line with the right people, had the right roommates. If he felt something was wrong, he was there to make sure I got back on the right track.

Mays’ journey to the majors was complete, a journey that seems hard to comprehend in today’s world. Not just because of the racial barriers he and others broke down but because signing players mostly was a free-for-all before the amateur draft was implemented in 1965. Before that, teams with the most money and best scouting network often landed the prime players. Scouts would travel the country building relationships with players’ families and searching for hidden gems. There were few rules. When pursuing Negro League players, there virtually were no rules.

Want to keep reading? Download 24: Life Stories and Lessons from the Say Hey Kid today!