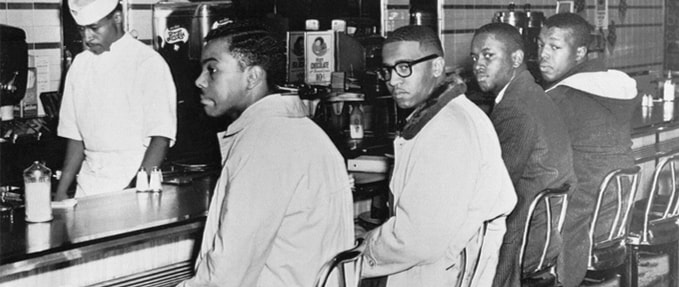

On February 1st, 1960, four Black college students sat down at a lunch counter and launched a movement. Like many lunch counters in the American South, the one at the Woolworth department store in Greensboro, North Carolina, refused to serve African Americans. Although the Greensboro Four, as they would come to be known, were not the first to conduct a sit-in against desegregation, it was, without a doubt, the most famous for enacting widespread attention and sparking change.

All students from North Carolina Agricultural and Technical College, Jibreel Khazan, Franklin McCain, Joseph McNeil, and David Richmond, were inspired by the nonviolent protest methods of Mohandas Gandhi and the Freedom Rides by the Congress for Racial Equality in 1947. The heinous murder of a young Black boy named Emmett Till in 1955, after he allegedly whistled at a white woman, was a further catalyst.

On that fateful day in Greensboro, the four students, although told to give up their seats as the official policy was to serve only whites, remained in place. When the police arrived, they were unable to take action because of the sit-in's peaceful nature. Local media arrived, and the men stayed until the store closed, only to return the next day with more students.

Soon, the movement would spread throughout the South and is today considered a defining example of nonviolent civil disobedience in American history. Despite in many cases being heckled, harassed, arrested for trespassing or disorderly conduct, the four students, and later the 70,000 participants that would become involved within months, stayed steadfast in their purpose, refusing to adhere to the unjust laws of segregation, and bringing about real change.

By the summer of 1960, the movement had spread to 55 cities in 13 states, and as a result, dining facilities, including Greensboro Woolworth’s, were integrated. Four Black employees at Woolworths, Geneva Tisdale, Susie Morrison, Anetha Jones, and Charles Best, were among the first to be served.

In The Sit-Ins, Christopher W. Schmidt, a professor at Chicago-Kent College of Law, narrates the trajectory of the sit-ins—how they began among four students, became a nationwide movement, and are now recognized as a turning point in Black and American history. All in all, Schmidt considers the role Americans played in contesting and shaping the Constitution.

In fact, the movement’s most significant action did not take place in the courts but rather among the people, peacefully protesting day after day, refusing to be dismissed. That being said, the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was made by Congress, not the Supreme Court, outlawing discrimination of any kind and prohibiting desegregation—a motion for change that began at a lunch counter four years prior.

As Schmidt outlines, in this excerpt and beyond, the sit-ins are a key example of what civil disobedience is—and more than that, what it can accomplish.

For a preview of The Sit-Ins, read on—then download the book today.

Greensboro

When Ezell Blair, Franklin McCain, Joseph McNeil, and David Richmond walked into the Greensboro Woolworth on the afternoon of February 1, 1960, their demonstration could very well have followed the pattern of these earlier sit-ins. They could have gotten some local attention. They could have convinced a local restaurant operator to stop discriminating. Maybe, as in Oklahoma, they could have even inspired others to follow. But this time, to everyone’s surprise, including the four freshman who started it all, things turned out quite differently.

From the first afternoon sitting at the Woolworth lunch counter, the Greensboro Four knew what they wanted. They wanted to be served while seated at the counter, just like any other paying customers. They wanted to demonstrate—to themselves, to their classmates, to their parents, to the whites who defended segregation—the severity of the injustice of racial discrimination and their commitment to doing something about it. Beyond this, as they were the first to admit, they had no elaborate plan of action. In the end, their February 1 sit-in is best described, in the words of historian Clayborne Carson, as “a simple, impulsive act of defiance.”

As more protesters joined the sit-ins in Greensboro, the demands of organizing and negotiation forced themselves upon the students. Thus began an often uneasy dance between the inspired spontaneity that brought the movement to life and the inescapable demands for strategy and guidance. Three days into the protest, the head of the Greensboro NAACP, George Simkins—who had no experience with and assumed the national NAACP office had little interest in this kind of protest—contacted CORE for help. Two CORE field secretaries headed to the South to conduct workshops in nonviolent protests, while others organized pickets of Woolworth and Kress stores in the North. CORE was the first of the national civil rights organizations to take decisive action in support of the students.

As the Greensboro sit-ins gained strength, the opposition mobilized. On the fifth day of the sit-ins, with protesters numbering in the hundreds, the local Ku Klux Klan arrived in downtown Greensboro, joining forces with what one reporter described as “young white toughs with ducktail haircuts.” “There were loud rebel yells, catcalls and clapping by white teen-agers along with shouts of ‘tear him to pieces’ and loud profanity.” When these “toughs” paraded around waving Confederate flags, black students responded by waving American flags. As the tension rose, student spokespersons emphasized the need to maintain the decorum that they felt was integral to the protest. “We don’t expect violence,” one explained, “but if it comes we will meet it with passive resistance. This is a Christian movement.” The police were there in force, with over thirty plainclothes and uniformed officers on the scene. Officers escorted a number of white men and women who were verbally abusing the protesters out of the store and arrested three white men—one for drunkenness, one particularly vocal person for disorderly conduct, and one who tried to set fire to a protester’s coat for assault.

That night, student leaders found themselves in a two-and-a-half-hour meeting with representatives from the local Woolworth and Kress stores and administrators from the area colleges (who were generally sympathetic toward the students’ cause but not their tactics). The store managers agreed to a two-week study period to investigate whether local custom would allow for an integrated seating policy, but only if the students halted their sit-ins. When the student leaders shared their proposal at a meeting of about fourteen hundred students (which they did “without conviction,” complained the chancellor of the Greensboro branch of the University of North Carolina, who was leading the negotiations), it was unanimously rejected. The sit-ins continued.

The next day was Saturday, and the sit-in protesters were waiting outside the Woolworth when it opened. Soon some six hundred people—integrationists, segregationists, newspaper reporters, and curious onlookers—crammed into the eating area. Around midday someone called the store to say there was a bomb in the basement. The police emptied the store, but they found no bomb. “The Negro students set up a wild round of cheering as the announcement of closing was made and carried their leaders out on their shoulders,” reported the local newspaper. They moved on to the nearby Kress store, which promptly shut down. Then they marched back to campus, chanting, “It’s all over” and “We whipped Woolworth.” Police blockaded the street behind them to prevent the white counter-protesters from following. The mayor issued a statement that praised the students for being “orderly and courteous,” asserted that “peace and good order will be preserved throughout our city,” and called on students and business operators to find a “just and honorable resolution of this problem.” That night the students held another mass meeting. This time, they agreed to a two-week sit-in moratorium, for the purpose of “negotiation and study.” When the Woolworth and Kress stores reopened on Monday, they kept their lunch counters closed. The first stage of the Greensboro sit-ins had come to a close.

The Spark Catches

By this point, just a week after the Greensboro Four made their fateful decision to sit at the Woolworth lunch counter, the protests, which had gained the attention of the local and national press, inspired college students in other North Carolina cities to start their own sit-ins. On February 8, students in Durham and Winston-Salem started protests at their local lunch counters. In the following days, students in Charlotte, Raleigh, Fayetteville, Elizabeth City, High Point, and Concord joined what quickly became a statewide movement.

This first wave of North Carolina sit-ins followed the Greensboro model. They often started with a bold, spontaneous act. The Winston-Salem sit-ins began when Carl Matthews, an African American graduate of the Winston-Salem Teachers College who worked at a local factory, sat down at the lunch counter of the Kress store in the middle of the lunch rush. He asked for service and was refused. A waitress eventually gave him a glass of water. Matthews sat and smoked. In the middle of the afternoon, six other African Americans, several of whom were students at the Teachers College, joined him. In Raleigh, protests were sparked by a local radio announcer who confidently predicted that area college students would not follow Greensboro’s lead. Intent on proving him wrong, the following morning a group of students went downtown and the Raleigh movement began.

As in Greensboro, white counter-protesters flocked to the sit-ins, and with them came sporadic acts of violence and threats of more serious retribution. White youths threw eggs at black students seated at the Woolworth lunch counter in Raleigh. The protesters “gave no reaction either to this or to jeers and catcalls thrown at them,” a reporter noted. Bomb threats became a common tactic for disrupting sit-ins. After a bomb threat shut down a Durham Woolworth store where some forty students (including four white students from Duke University) were engaged in a sit- in, protesters turned their attention to other segregated lunch counters in the downtown area, closing them down too.

These early North Carolina protests also displayed important variations from the Greensboro template. In High Point, high school rather than college students initiated the sit-ins, and they received close guidance from adult civil rights leaders. Before their first sit-in, they had reached out to a supportive local NAACP official. For their first day of sit-ins, the students had impressive leadership: Fred Shuttlesworth, the firebrand Birmingham-based civil rights activist who happened to be visiting North Carolina when the sit-ins broke out, and Douglas Moore, a North Carolina civil rights leader. (After participating in the first High Point sit-in, Shuttlesworth called Ella Baker, executive director of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), in Atlanta and asked her to pass on a message to his close friend Martin Luther King Jr. “You must tell Martin that we must get with this,” he said. The sit-ins “can shake up the world.”) The High Point protests also ran into some new obstacles. The day after sit-in protests led to a shutdown of two variety store lunch counters, a local merchant paid off a group of white high school students to arrive early and occupy all the lunch counter stools at the Woolworth so the black protesters had nowhere to sit. When they came back the next day, the store had converted its lunch counter into a display counter and each stool was adorned with a box of Valentine chocolates. The students converted their sit-in to a stand-in and stood vigil over the chocolates through the morning. When large numbers of whites and black adults arrived, curious to see this unusual demonstration, the manager took police advice and shut down the entire store.

On February 10, Hampton, Virginia, became the first city outside North Carolina to become a target of sit-in protests. The next day, sit-ins spread to two more Virginia cities, Norfolk and Portsmouth. Meanwhile, sit-ins broke out in new cities in North Carolina: Salisbury on February 16; Shelby on the eighteenth; Henderson on the twenty-fifth; Chapel Hill on the twenty-eighth.

The first student arrests of the movement occurred on February 12. For several days, students had been targeting a Woolworth store at a shopping center outside Raleigh. After they once again forced the manager to shut down his lunch counter, the protesters gathered on a sidewalk outside the store to decide their next move. The manager of the shopping center informed police, who were already on the scene, that he wanted to bring trespassing charges against the students, and forty-one students were arrested. The students secured a lawyer, who promptly denounced the sidewalk arrests as a violation of the students’ First Amendment rights and vowed to take the case to the U.S. Supreme Court if necessary. The students took their lawyer’s advice to put a hold on protests at the shopping center pending the outcome of their court cases. They were convicted and fined $10 each, but state courts quickly overturned their convictions.

On the same day of the mass arrest in Raleigh, lunch counter protests spread deeper into the South. Students in Deland organized the movement’s first Florida sit-in. In a widely reported event, about a hundred demonstrators sat in at two lunch counters in Rock Hill, South Carolina. The Rock Hill protest attracted the attention of white youths, “mostly teenaged boys with duck-tail haircuts,” according to the New York Times reporter on the scene. Some of these “angry whites,” the reporter added, “appeared to be juvenile delinquents.” One of the delinquents knocked a black protester from his stool; another threw an egg at a demonstrator. Someone threw a bottle of ammonia into a store, setting off fumes that stung the eyes of the demonstrators inside. Bomb threats then cleared everyone out of both the targeted stores. The New York Times put the Rock Hill protest on its front page—another first for the sit-in movement.

On February 13, students in Nashville joined the sit-in movement. In fact, Nashville students had been planning a protest campaign targeting downtown lunch counters for months. (“In an orderly and logical world,” wrote one historian, “the great wave of student sit-ins that washed across the South early in 1960 should have flowed outward from Nashville.”) Reverend James Lawson, an African American divinity student at Vanderbilt University, led preparations. Lawson was the project’s director for the Nashville Christian Leadership Council, an affiliate of Martin Luther King Jr.’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference. A devoted follower of the nonviolent principles espoused by Mahatma Gandhi, Lawson had served a prison sentence for his refusal to report for the draft during the Korean War and then spent three years in India as a Christian missionary. In 1958 he began leading workshops in Nashville on nonviolent protest techniques, and in late 1959 he helped organize small-scale test sit-ins of local lunch counters, with the goal of confirming targets for sit-in protests that would begin after the holidays.

When the Greensboro protests began on February 1, students in Nashville had yet to follow through on their plans. Lawson called a meeting to discuss whether the students in Nashville were ready to act. Older blacks who attended the meeting urged the students to delay, concerned that they needed time to line up a lawyer and raise money to have on hand for bail if the students were arrested. Another week passed before the Nashville protests began.

Over a hundred students, including about ten whites, joined the first Nashville sit-ins. The protests were carefully organized, orderly, and relatively uneventful. Five days later, the next round of sit-ins brought out some two hundred students. Two days later, an estimated 350 students targeted four downtown variety stores. Each of the stores closed when the demonstrators appeared. Police were present throughout but made no arrests. Then another week passed before the next round of protests. This time students targeted five downtown stores. A young reporter named David Halberstam (who would go on to become one of the most prominent journalists of his generation) wrote the following account:

“The scene was Woolworth’s, and it was an almost unbelievable study in hate. The police were outside the store at the request of the management. Inside were almost 350 people, all watching the counter like spectators at a boxing match. To the side of the counter, on the stairs leading to the mezzanine, was a press gallery of reporters and photographers. At the counter were the Negroes, not talking to each other, just sitting quietly and looking straight ahead. Behind them were the punks.”

According to Antoinette Brown, a student from New York who took part in the Nashville sit-ins, it felt “inevitable” that the situation would explode. “There is going to be bloodshed. I can feel it everywhere.” “The slow build up of hate was somehow worse than the actual violence,” Halberstam wrote. “The violence came quickly enough, however.” For more than an hour, the assaults against the demonstrators escalated—taunting, spitting, hitting, first slaps, then blows; then banging the demonstrators’ heads against the counter and dropping hot cigarette butts down the backs of their shirts. White boys dragged three of the black male protesters from their stools and started beating them. “The three Negroes did not fight back, but stumbled and ran out of the store; the whites, their faces red with anger, screamed at them to stop and fight, to please goddam stop and fight. None of the other Negroes at the counter ever looked around. It was over in a minute.” At this point, the police stepped in, arresting eighty-one sit-in protesters (but no whites) on charges of disorderly conduct.

By the end of March, just two months after the first sit-ins in Greensboro, the student protest movement had spread to eleven states and sixty-five cities in the South. Students from over forty colleges and universities had taken part in the movement. In the words of a writer for the Chicago Defender, the sit-ins “ripped through Dixie with the speed of a rocket and the contagion of the old plague.”

Want to keep reading? Download The Sit-ins today.

Featured image: Jack Moebes / Corbis