In 1948, when biologist Farley Mowat began his field studies in the subarctic regions of southern Keewatin Territory and northern Manitoba, he never thought he’d write a book about wolves. His intent was not to write about animals at all, but about humans and the roles we have come to assume in society. While in the wilderness for two summers and a winter, the federal government of Canada employed him to observe the wolves and caribou, two species he viewed as secondary characters in his narrative. But what Mowat saw would cause him to rethink everything he was taught to believe about wolves.

In articulating his solo journey through the region, Mowat learns from the Ihalmiut, an Inuit tribe, about how to foster a kinship with the environment and, more specifically, with the species. Despite many scientists initially dismissing the book as fiction, Mowat would prove right in his findings: the wolf is not a threat to humans or in need of taming. As the author brilliantly articulates in the preface, “We have doomed the wolf not for what it is but for what we deliberately and mistakenly perceive it to be: the mythologized epitome of a savage, ruthless killer—which is, in reality, no more than the reflected image of ourself.”

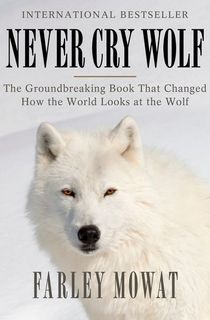

In this excerpt from Never Cry Wolf, which was adapted into a 1983 film, Mowat details his first encounter with a wolf. It is the beginning of a journey that will set Mowat on a different path, one that reconfigures his relationship with himself, and then the world. In the process, he reminds readers that just because things have always been believed to be a certain way doesn’t mean they should continue as such.

As I was a newcomer to the Barrens, it behooved me to familiarize myself with the country in a cautious manner. Hence, on my first expedition afield I contented myself with making a circular tour on a radius of about three hundred yards from the cabin.

This expedition revealed little except the presence of four or five hundred caribou skeletons; indeed, the entire area surrounding the cabin seemed to be carpeted in caribou bones. Since I knew from my researches in Churchill that trappers never shot caribou, I could only assume that these animals had been killed by wolves. This was a sobering conclusion. Assuming that the density of the caribou kill was uniform over the whole country, the sample I had seen indicated that wolves must kill, on the average, about twenty million caribou a year in Keewatin alone.

After this dismaying tour of the boneyard it was three days before I found time for another trip afield. Carrying a rifle and wearing my revolver, I went a quarter-mile on this second expedition—but saw no wolves. However, to my surprise I observed that the density of caribou remains decreased in an almost geometric ratio to the distance from the cabin. Sorely puzzled by the fact that the wolves seemed to have chosen to commit their worst slaughter so close to a human habitation, I resolved to question Mike about it if or when I saw him again.

Meantime spring had come to the Barrens with volcanic violence. The snows melted so fast that the frozen rivers could not carry the melted water, which flowed six feet deep on top of the ice. Finally the ice let go, with a thunderous explosion; then it promptly jammed, and in short order the river beside which I was living had entered into the cabin, bringing with it the accumulated refuse left by fourteen Huskies during a long winter.

Eventually the jam broke and the waters subsided; but the cabin had lost its charm, for the debris on the floor was a foot thick and somewhat repellent. I decided to pitch my tent on a gravel ridge above the cabin, and here I was vainly trying to go to sleep that evening when I became aware of unfamiliar sounds. Sitting bolt upright, I listened intently.

The sounds were coming from just across the river, to the north, and they were a weird medley of whines, whimpers and small howls. My grip on the rifle slowly relaxed. If there is one thing at which scientists are adept, it is learning from experience; I was not to be fooled twice. The cries were obviously those of a Husky, probably a young one, and I deduced that it must be one of Mike’s dogs (he owned three half-grown pups not yet trained to harness which ran loose after the team) that had got lost, retraced its way to the cabin, and was now begging for someone to come and be nice to it.

I was delighted. If that pup needed a friend, a chum, I was its man! I climbed hastily into my clothes, ran down to the riverbank, launched the canoe, and paddled lustily for the far bank.

The pup had never ceased its mournful plaint, and I was about to call out reassuringly when it occurred to me that an unfamiliar human voice might frighten it. I decided to stalk it instead, and to betray my presence only when I was close enough for soothing murmurs.

From the nature of the sounds I had assumed the dog was only a few yards away from the far bank, but as I made my way in the dim half-light, over broken boulders and across gravel ridges, the sounds seemed to remain at the same volume while I appeared to be getting no closer. I assumed the pup was retreating, perhaps out of shyness. In my anxiety not to startle it away entirely, I still kept quiet, even when the whimpering wail stopped, leaving me uncertain about the right direction to pursue. However, I saw a steep ridge looming ahead of me and I suspected that, once I gained its summit, I would have a clear enough view to enable me to locate the lost animal. As I neared the crest of the ridge I got down on my stomach (practicing the fieldcraft I had learned in the Boy Scouts) and cautiously inched my way the last few feet.

My head came slowly over the crest—and there was my quarry. He was lying down, evidently resting after his mournful singsong, and his nose was about six feet from mine. We stared at one another in silence. I do not know what went on in his massive skull, but my head was full of the most disturbing thoughts. I was peering straight into the amber gaze of a fully grown arctic wolf, who probably weighed more than I did, and who was certainly a lot better versed in close-combat techniques than I would ever be.

For some seconds neither of us moved but continued to stare hypnotically into one another’s eyes. The wolf was the first to break the spell. With a spring which would have done justice to a Russian dancer, he leaped about a yard straight into the air and came down running. The textbooks say a wolf can run twenty-five miles an hour, but this one did not appear to be running, so much as flying low. Within seconds he had vanished from my sight.

My own reaction was not so dramatic, although I may very well have set some sort of a record for a cross-country traverse myself. My return over the river was accomplished with such verve that I paddled the canoe almost her full length up on the beach on the other side. Then, remembering my responsibilities to my scientific supplies, I entered the cabin, barred the door, and regardless of the discomfort caused by the stench of the debris on the floor made myself as comfortable as I could on top of the table for the balance of the short-lived night.

It had been a strenuous interlude, but I could congratulate myself that I had, at last, established contact—no matter how briefly—with the study species.

6

The Den

What with one thing and another I found it difficult to get to sleep. The table was too short and too hard; the atmosphere in the cabin was far too thick; and the memory of my recent encounter with the wolf was too vivid. I tried counting sheep, but they kept turning into wolves, leaving me more wakeful than ever. Finally, when some red-backed mice who lived under the floor began to produce noises which were realistic approximations of the sounds a wolf might make if he were snuffling at the door, I gave up all idea of sleep, lit Mike’s oil lantern, and resigned myself to waiting for the dawn.

I allowed my thoughts to return to the events of the evening. Considering how brief the encounter with the wolf had been, I was amazed to discover the wealth of detail I could recall. In my mind’s eye I could visualize the wolf as if I had known him (or her) for years. The image of that massive head with its broad white ruff, short pricked ears, tawny eyes and grizzled muzzle was indelibly fixed in memory. So too was the image of the wolf in flight; the lean and sinewy motion and the overall impression of a beast the size of a small pony; an impression implicit with a feeling of lethal strength.

The more I thought about it, the more I realized that I had not cut a very courageous figure. My withdrawal from the scene had been hasty and devoid of dignity. But then the compensating thought occurred to me that the wolf had not stood upon the order of his (her) going either, and I began to feel somewhat better; a state of mind which may have been coincidental with the rising of the sun, which was now illuminating the bleak world outside my window with a gray and pallid light.

As the light grew stronger I even began to suspect that I had muffed an opportunity—one which might, moreover, never again recur. It was borne in upon me that I should have followed the wolf and endeavored to gain his confidence, or at least to convince him that I harbored no ill will toward his kind.

The Canada jays who came each day to scavenge the debris in the dooryard were now becoming active. I lit the stove and cooked my breakfast. Then, filled with resolution, I packed some grub in a haversack, saw to the supply of ammunition for my rifle and revolver, slung my binoculars around my neck, and set out to make good my failure of the previous evening. My plan was straightforward. I intended to go directly to the spot where I had seen the wolf disappear, pick up his trail, and follow until I found him.

The going was rough and rocky at first, and I took a good deal longer to cover the intervening ground than the wolf had done, but eventually I scaled the low crest where I had last seen him (or her). Ahead of me I found a vast expanse of boggy muskeg which promised well for tracks; and indeed I found a set of footprints almost immediately, leading off across a patch of chocolate-colored bog.

I should have felt overjoyed, yet somehow I did not. The truth is that my first sight of the wolf’s paw-prints was a revelation for which I was quite unprepared. It is one thing to read in a textbook that the footprints of an arctic wolf measure six inches in diameter; but it is quite another thing to see them laid out before you in all their bald immensity. It has a dampening effect on one’s enthusiasm. The mammoth prints before me, combined as they were with a forty-inch stride, suggested that the beast I was proposing to pursue was built on approximately the scale of a grizzly bear.

I studied those prints for quite a long time, and might perhaps have studied them for even longer had I not made the discovery that I had neglected to bring my pocket compass with me. Since it would have been foolhardy to proceed into an unmarked wilderness without it, I regretfully decided to return to the cabin.

When I got back to Mike’s the compass was not where I had left it. In fact I couldn’t remember where I had left it, or even if I had seen it since leaving Ottawa. It was an impasse; but in order not to waste my time I got down one of the standard works with which the Department had equipped me, and consulted the section on wolves. I had, of course, read this section many times before, but some of the salient facts had evidently failed to impress themselves clearly on my mind. Now, with my capacity for mental imagery sharpened by my first look at a set of real wolf tracks, I reread the piece withnew interest and appreciation.

Arctic wolves, the author informed me, were the largest of the many subspecies or races of Canis lupus. Specimens had been examined which weighed one hundred and seventy pounds; which measured eight feet seven inches from tip of nose to tip of tail; and which stood forty-two inches high at the shoulders. An adult of the arctic race could eat (and presumably did on favorable occasions) thirty pounds of raw meat at a sitting. The teeth were “massive in construction and capable of both rending and grinding action, which enables the owner to dismember the largest mammals with ease, and crush even the strongest bones.” The section closed with the following succinct remarks: “The wolf is a savage, powerful killer. It is one of the most feared and hated animals known to man, and with excellent reason.” The reason was not given, but it would have been superfluous in any case.

To keep reading, download Never Cry Wolf today!

Featured photo: Annie Spratt / Unsplash

This post is sponsored by Open Road Media. Thank you for supporting our partners, who make it possible for The Archive to continue publishing the history stories you love.