The River Thames is usually described as steady and familiar, a place around which London took shape. But, for long stretches of its past, that was not how it behaved at all.

The river was narrow in places, packed with traffic, and edged with arguments that rarely stayed verbal for long. It was a working space before it became a symbol, bearing the city's pressures directly on its surface.

Before railways reached London, almost everything heavy came by water. Grain, firewood, stone, barrels of beer, and even household goods moved along the Thames day after day.

For the men who worked it, the river was not picturesque. Time mattered on the river—a delay could cost a day’s pay, and damage often meant borrowing to stay afloat. Many earned their living directly on the Thames, while others relied on it quietly, without ever setting foot in a boat.

Rivalries on a Crowded River

By the later Middle Ages, congestion on the Thames was constant. Barges edged past ferries, fishing boats cut across loaded craft, and private vessels forced their way into gaps that barely existed.

Additionally, authority was fragmented, with city officials, guilds, and private operators each claiming influence, yet no single entity controlled the river. Disputes over landing stairs and passage fees became routine, and many ended with damaged boats rather than written complaints.

Repeatedly, discourse between watermen and merchants surfaces in the records, with licensed operators defending their rights closely, particularly when unlicensed boats appeared along familiar routes. Court documents refer to assaults, damaged gear, and threats exchanged in full view of others.

Few working on the river had room for error: losing an oar or splitting a hull could keep a man off the water for weeks, while falling into the river while fully clothed was often fatal. Arguments escalated because the risks were understood intuitively, even if they were never fully articulated.

After Dark on the Thames

After dark, the Thames became harder to read and harder to control. Once evening traffic thinned, the river offered privacy of a dangerous kind. There were few lights along the banks, and patrols were irregular at best.

Boats collided in poor visibility. Passengers were robbed. Arguments that might have cooled during the day hardened at night. Coroners’ inquests from the period frequently record bodies recovered from the river without a clear explanation.

Some deaths were plainly accidental. Others arrived after arguments earlier in the evening, leaving officials to determine whether the river alone was responsible or whether another party had been involved.

All in all, the Thames readily absorbed responsibility. If a death could not be proven criminal, no one was punished—the water carried the evidence away.

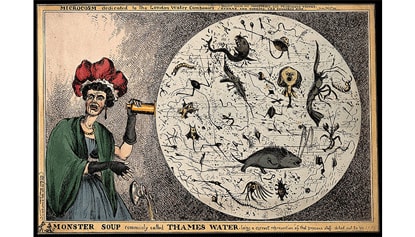

Satirical cartoon showing a woman observing monsters in a drop of London water (1828).

Photo Credit: William Heath / Wikimedia CommonsSamuel Pepys and the Risk of River Travel

Samuel Pepys wrote about the Thames because he spent most of his time travelling along it. Boats were part of his daily movement around London, and the river appears in his diary in passing, noted almost without ceremony, as something to be endured as much as relied upon.

In August 1660, Pepys noted how tightly packed the boats had become, so close that collisions were difficult to avoid. Elsewhere, he mentioned rough crossings and boatmen whose behavior left him uneasy or irritated. The entries are short, sometimes almost throwaway, but the risk is there in the background, returning often enough to be hard to ignore.

Pepys also remarked on the effects of drink, especially during periods of celebration. The Thames, like the streets nearby, became more volatile when alcohol flowed freely. But the difference was that mistakes on the river were less forgiving.

Civil War on the Water

The English Civil War brought political tension directly onto the Thames. By the early 1640s, the river had become both strategically and economically vital. Supplies moved by boat. Messages crossed the water. Control of bridges and ferries mattered in ways that were suddenly obvious.

John Evelyn’s diary reflects the atmosphere of suspicion that settled over London during these years. Movement along the river was watched closely. Ferrymen were questioned. Boats were searched. The Thames became a place where loyalty was tested as much as cargo.

Skirmishes occurred along the banks, and vessels were occasionally seized. Ordinary journeys took on new meaning. A delayed crossing could be interpreted as sympathy for the wrong side. The river, already strained by daily competition, now carried the weight of civil conflict as well.

When the Thames Froze Solid

In the coldest winters, the Thames did not behave like a river at all. During the harshest years of the Little Ice Age, the surface froze sufficiently to support people, animals, and improvised structures. Stalls appeared on the ice, selling food, drinks, and printed scraps intended to mark the occasion.

Engravings suggest cheerful order, but they flatten what was often a tense and unstable situation. Drinking was constant, and tempers followed. Pickpocketing and fights are mentioned repeatedly, especially near the banks where the ice was weakest.

The ice shifted unpredictably, sometimes giving way beneath groups that had only just arrived. As such, deaths during frost fairs are frequently recorded in surviving accounts, where people fell through weakened ice or were caught in sudden surges of panic.

For those who relied on river traffic for income, the freeze brought work to a halt and, with it, uncertainty. Barges were trapped. Supplies failed to move. Prices climbed as shortages spread. The strain showed itself across the city, but it began on the river, where movement had stopped entirely.

Frost Fair on the Thames (1685).

Photo Credit: Wikimedia CommonsOrdinary Lives, Quiet Deaths

The people most affected rarely appear by name. They were laborers, boatmen, apprentices, and passengers going about ordinary routines. When death followed, the record was often sparse, sometimes limited to a place and a date.

A body was recovered near a landing stair. A ferryman was injured during an argument over payment. These entries appear without commentary, their context assumed rather than explained. Individually, they seem minor. Taken together, they reveal a river that was consistently dangerous and closely linked to social tensions.

The Thames did not need formal battles to claim lives. Overall, crowding, competition, and weak oversight were enough.

Bringing Order to the Water

Over time, London imposed greater control. Licensing tightened. Policing improved. Embankments reshaped the river’s edges. Bridges multiplied, reducing reliance on ferries. By the eighteenth century, the most violent aspects of river life had begun to fade.

But even as regulation increased, the effects of earlier conflict lingered. The river had shaped habits, institutions, and expectations long before it was properly controlled.

Today, the Thames is settled, carefully managed, and closely watched. For much of its past, it was not. The river brought work, anger, and risk into close proximity, and survival often hinged on timing rather than strength or experience.

Featured image: Canaletto / Wikimedia Commons