While often labeled “the forgotten war,” the Korean War left a distinct stain on the collective memory of the American military community.

The short, but extremely bloody, conflict saw hundreds of thousands of soldiers and civilians die from combat and non-battle causes—forcing America to reevaluate how it had approached the war. The first war in which the United Nations took part, the Korean War exposed discrepancies between calculated diplomacy, a nation’s moral imperative, military readiness, and the innate complexities of warfare—all issues that T.R. Fehrenbach’s This Kind of War examines in detail.

Fehrenbach’s book has been regarded as essential reading by military-minded leaders in America, including Alaska Senator Dan Sullivan, a Marine Corps Reserve lieutenant colonel who served in Afghanistan, and U.S. Secretary of Defense Jim Mattis. While North and South Korea seem to have found some kind of peace as they recently agreed to denuclearize the Korean Peninsula, Fehrenbach’s work—as a definitive and cautionary tale about the promises and perils of military action—is still a particularly timely perspective.

Read on for an excerpt from This Kind of War, which offers a blow-by-blow account and analysis of America’s past military action in the Korean Peninsula.

More than anything else, the Korean War was not a test of power—because neither antagonist used full powers—but of wills. The war showed that the West had misjudged the ambition and intent of the Communist leadership, and clearly revealed that leadership’s intense hostility to the West; it also proved that Communism erred badly in assessing the response its aggression would call forth.

The men who sent their divisions crashing across the 38th parallel on 25 June 1950 hardly dreamed that the world would rally against them, or that the United States — which had repeatedly professed its reluctance to do so—would commit ground forces onto the mainland of Asia.

From the fighting, however inconclusive the end, each side could take home valuable lessons. The Communists would understand that the free world—in particular the United States—had the will to react quickly and practically and without panic in a new situation. The American public, and that of Europe, learned that the postwar world was not the pleasant place they hoped it would be, that it could not be neatly policed by bombers and carrier aircraft and nuclear warheads, and that the Communist menace could be disregarded only at extreme peril.

The war, on either side, brought no one satisfaction. It did, hopefully, teach a general lesson of caution.

The great test placed upon the United States was not whether it had the power to devastate the Soviet Union—this it had—but whether the American leadership had the will to continue to fight for an orderly world rather than to succumb to hysteric violence. Twice in the century uncontrolled violence had swept the world, and after untold bloodshed and destruction nothing was accomplished. Americans had come to hate war, but in 1950 were no nearer to abolishing it than they had been a century before.

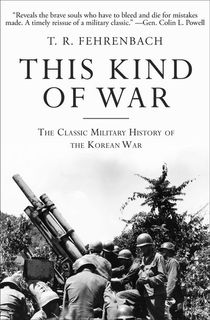

U.S. Marines move out over rugged mountain terrain while closing with North Korean forces.

Photo Credit: WikipediaBut two great bloodlettings, and the advent of the Atomic Age with its capability of fantastic destruction, taught Americans that their traditional attitudes toward war—to regard war as an unholy thing, but once involved, however reluctantly, to strike those who unleashed it with holy wrath—must be altered. In the Korean War, Americans adopted a course not new to the world, but new to them. They accepted limitations on warfare, and accepted controlled violence as the means to an end. Their policy—for the first time in the century—succeeded. The Korean War was not followed by the tragic disillusionment of World War I, or the unbelieving bitterness of 1946 toward the fact that nothing had been settled. But because Americans for the first time lived in a world in which they could not truly win, whatever the effort, and from which they could not withdraw, without disaster, for millions the result was trauma.

During the Korean War, the United States found that it could not enforce international morality and that its people had to live and continue to fight in a basically amoral world. They could oppose that which they regarded as evil, but they could not destroy it without risking their own destruction.

Because the American people have traditionally taken a warlike, but not military, attitude to battle, and because they have always coupled a certain belligerence—no American likes being pushed around—with a complete unwillingness to prepare for combat, the Korean War was difficult, perhaps the most difficult in their history.

In Korea, Americans had to fight, not a popular, righteous war, but to send men to die on a bloody checkerboard, with hard heads and without exalted motivations, in the hope of preserving the kind of world order Americans desired.

Tragically, they were not ready, either in body or in spirit.

They had not really realized the kind of world they lived in, or the tests of wills they might face, or the disciplines that would be required to win them.

Yet when America committed its ground troops into Korea, the American people committed their entire prestige, and put the failure or success of their foreign policy on the line.

Want to keep reading? Download This Kind of War now.

This post is sponsored by Open Road Media. Thank you for supporting our partners, who make it possible for The Archive to continue publishing the history stories you love.

Featured image of a U.S. howitzer position near the Kum River: Wikipedia