Early on August 17, 1916, under the red glow of a falling flare, Second Lieutenant Will Harvey made his way through the front line trench. The narrow passages were sunk a few feet into the earth, then built up with sandbag walls that rose high over his head, resembling crenellated battlements. Duckboards covered the trench floor, but the slick planks were not enough to prevent his boots sinking into the river of mud beneath as he pushed through the mass of soldiers who inhabited this bleak underworld.

Those on sentry duty stood up on the fire step, rifles in hand, peering into the dark for any hint of a German advance. Others worked to shore up crumbling walls, hauled supplies, rebuilt parapets destroyed by shelling. Some clambered back down into the trench after fixing a patch of barbwire in no-man’s-land. Those who were off duty huddled along the passageways, smoking cigarettes, brewing tea on charcoal braziers, or trying to catch a couple of hours of restless sleep amid a scurry of rats.

Harvey continued through the trench, checking on his platoon in the 5th Battalion, Gloucestershire Regiment. He did not look like the typical decorated officer. “I never saw anyone less like a hero in my life,” one soldier wrote. “Imagine a small, dirty, nearly middle-aged man, wearing glasses and an apologetic air, trudging along the pavé under a huge pack . . . He looks as if he stuffed birds in civil life.” At twenty-eight years of age, Harvey was hardly middle-aged, but his short, sturdy frame and soft round face made him easily forgettable. Few have better proved that a book is best not judged by its cover.

Only the day before, his battalion had moved into the Fauquissart sector. Near the village of Neuve Chapelle, site of a fierce onslaught by the British across two thousand yards of no-man’s-land in March 1915, the area was now in a state of relative calm. They were far north of the Somme, the latest fixation of the Allies in their attempt to break the stalemate of the Western Front.

British troops in 1917.

Photo Credit: WikipediaBefore dawn came the chilling call of “Stand to!” Soldiers scrambled to take their positions along the parapet wall with fixed bayonets, knowing well that the rising sun often brought an enemy attack. In the silence that followed, Harvey and his men stared across the tangled hedges of barbwire for any sign of movement. Minute after minute passed, but the only assault came from the swarms of fetid, blue-bellied flies that thrived in the summer heat and flesh of the dead. An hour later, “Stand down” passed through the line, and drams of rum were given out.

The morning looked to be the usual start of another day in the trenches. Harvey tried to get some rest in a dugout, but he could not shake loose his thoughts about the patrol he was tasked to lead that evening. He had more experience — and success — with such dangerous missions than anyone in his battalion, but this did not ease his mind.

The British command wanted to ensure that the Germans did not divert resources from other areas to the Somme, and ordered sporadic raids up and down the line to keep them on edge. For the upcoming raid by Harvey’s battalion, a reconnaissance of the German trenches was considered necessary.

The more Harvey thought about it, the more determined he was to check out the terrain himself before venturing out with his men. This action might well save one of their lives. Once he had resolved to go out alone first, Harvey was able to shut his eyes and sleep for a couple of hours.

Later that morning, he searched out his friend from home, Ivor Gurney. Although they were in the same regiment, they rarely saw one another, given the shifting schedules of the trench. The two shared a love for poetry, music, and books. Harvey gave Gurney his pocket edition of The Spirit of Man by Robert Bridges, and they spent a few moments in conversation about Britain’s poet laureate, whose latest work urged his fellow countrymen to face the “intolerable grief ” of war by training their minds to “interpret the world according to [their] higher nature.”

In the early afternoon, Harvey sent word of his proposed scouting mission to his company officer, then alerted the British sentries about the same, to avoid being killed by friendly fire. At 2:00 p.m. he readied to go, a mud-stained copy of Shakespeare’s sonnets in his pocket as always. A sentry pulled aside the sally port in the parapet wall. Mouth dry from nerves, Harvey climbed through it. As the soldier returned the defense into place, Harvey wriggled across a stretch of tall grass that had somehow avoided being burned or destroyed by shelling.

Three hundred yards away stood the German lines. The next few hours were typically the part of the day when both sides rested before the long pitch of night. Few were on duty apart from the sentries — and even they were not at their keenest. Harvey hoped to reconnoiter a forward sap, a span of trench that ran out perpendicular from the enemy’s front line that was used as an observation post. He believed the sap was lightly defended or altogether unoccupied. If it was, it might serve as a point of attack in the upcoming raid.

An unsteady wind blew, rustling the tall grass, camouflaging Harvey as he moved forward on his stomach. When he came upon twists of barbwire, he either crawled over them or brushed them aside with the wooden bludgeon he always carried on such patrols. At times, he was hidden in shell holes or in the shadow of a short hedge that ran through this former farmland. Other times, he was all but exposed if he lifted up too high on his forearms.

Every move risked detection. If his equipment rattled, if he knocked into an unseen tin can or other piece of litter, he was lost. Although he held his bludgeon in one hand and an automatic pistol in the other, he knew that neither would serve much purpose if a German sniper spotted him. All the way forward, he made note of where the barbwire was thickest as well as any shell holes that might serve as temporary shelters from machine-gun fire.

He crawled down into a drain that ran toward the German parapet. Very close now. At this point, if he had been there with others, he would have turned back. Alone, confident in his ability, he inched onward until he reached the front line trench. Resting in the shadow cast by the stacked sandbags, he held his breath and trained his ears for any sound beyond: a cough, a whisper of conversation, a footfall, a cleared throat, a rifle stock shifted into place. There was nothing. Lifting his head slightly, he peered left and right along the parapet, searching for a spying German periscope or the top of a head. Nothing. After a few seconds, he rose slowly onto the parapet, then popped up to look down into the trench. It was empty.

There was no doubt he should return to his own line. He had scouted a path through no-man’s-land and had found a potential access point for the raid on the German trenches. Although his objective was fulfilled, he wanted to explore further, to see how much of this section was undefended. Every yard of weakness in the line he could scout would save many lives. He’d already come this far. “Be damned if I go back,” Harvey muttered to himself.

He heaved himself up and over the parapet wall into the trench. Unseen, he moved down the sap toward the adjoining traverse and peered down the path, finding it also to be empty. Creeping onward, pistol at the ready, he thought about hiding out in the German lines throughout the night, to scout their mortar placements and machine-gun nests. If he found an exit gap in the back wall of their trenches, he could lie in the grass until early morning. With this idea in mind, he searched for such a gap but found none.

Reaching the next turn in the line, he heard from behind him the sound of advancing soldiers. There was no going back. He continued on ahead, glancing left and right, urgently needing an exit now. The walls were uniform, tall, and without a break. On the next traverse, he turned the corner to discover a dugout braced with iron — a mortar shelter. He could hide there until whoever was coming from behind had passed. Rushing toward the doorway, he was suddenly confronted by two German soldiers on their way out. In his shock, Harvey did not have time to raise his pistol. The two men seized the poet-soldier of Gloucestershire with little trouble.

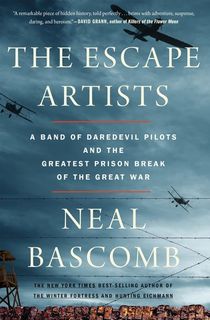

Want to keep reading? Download The Escape Artists now.

This post is sponsored by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Thank you for supporting our partners, who make it possible for The Archive to continue publishing the history stories you love.

Featured image of Kaserne B at Holzminden, with prisoners and guards: Wikipedia