If someone had walked into Erfurt on the morning of the Hoftag in 1184, they would have seen what looked like a fairly ordinary, if royal gathering. People were coming and going, messengers carried notes across the precinct, and groups of nobles stood talking in the narrow streets. Nothing about the day suggested that anything unusual was about to happen.

Henry VI, King of Germany, had asked everyone to assemble so he could calm a dispute that had dragged on for years. Most people expected a long session of arguments and explanations. The hall chosen for the meeting was old but functional, the sort of place where decisions were made without much ceremony. No one imagined that the building itself would become the center of the story.

A Long-Running Disagreement

The problem that brought everyone together was a familiar one. Conrad of Mainz and Louis of Thuringia had been arguing over land and authority for so long that many could barely remember how the conflict had begun.

These kinds of disputes were common in the Holy Roman Empire, where family claims and feudal obligations often overlapped in confusing ways. Henry VI knew that if he did not intervene, the situation could easily grow worse. So, he called the Hoftag, hoping that hearing both men in person might help steer the argument toward a settlement.

Royal assemblies tended to attract more people than strictly needed. Some came because their presence was expected, others out of loyalty, and a few because they enjoyed being where important matters were discussed. By the time the session began, the hall was so crowded that those standing near the walls could feel the pressure of bodies pressing forward.

A Hall Past Its Best Years

The meeting took place in a two-story timber structure in the cathedral precinct, where the upper floor held the assembly room, while the lower level included a few service spaces, one of which contained a cesspit. This arrangement likely made practical sense when the building was put together.

And yet the building was older than it looked. Years of damp winters, small repairs, and heavy use had weakened the beams beneath the floor. On an ordinary day, the structure held up well enough.

But on this particular morning, the crowd was larger and standing far closer together than usual, not to mention the armor, swords, and heavy clothing that added to the weight pressing down on the old timbers. If the floor creaked or shifted, the sound must have been swallowed by the noise of people talking, meaning that nothing was obvious enough to make anyone step back.

Depiction of King Henry VI from the Codex Manesse (1350).

Photo Credit: Wikimedia CommonsThe Collapse

The break came quickly, with several chroniclers commenting on a sudden crack that ran across the center of the hall. Before anyone could react, the planks gave way under the weight of the crowd. Those standing in the middle fell straight through, dragging pieces of the floor with them.

Their fall smashed through the ceiling of the lower level and ruptured the surface of the cesspit, beneath part of the structure. What had been a closed, contained space was torn open in an instant. Beams, tiles, splinters, clothing, and people dropped into the foul water below.

For a moment, the hall was filled with nothing but noise. Some men died as they hit the lower beams. Others landed in the water and debris, struggling to move while more parts of the building continued to fall. The mixture of waste and shattered timber made every movement difficult.

Survivors later described the mess below as almost impossible to navigate. The floor was slippery, the air heavy, and the wreckage shifted with every step. Some men managed to grab sections of timber or stone as they dropped, holding on until help reached them. Others tried to climb toward any visible opening. Many could not move at all, pinned under broken beams.

The number of deaths varies across accounts, but most people agree that around sixty people lost their lives. Some chroniclers suggest the toll was higher. However, the confusion of the scene makes exact numbers difficult to determine.

Accounts suggest that Henry VI only survived because he was close to a stone recess or window ledge and managed to grab it as the floor fell away. Once secure, attendants pulled him to safety. The men the assembly had gathered for, Conrad and Louis, survived as well, although many of their household men did not.

The Hoftag Ends in Tragedy

The noise of the collapse carried across the precinct, and people rushed toward the hall. When they reached the doorway, they faced a scene that did not make sense at first glance: the upper floor had vanished; the opening was filled with broken wood, and the lower level was dark and flooded; and the edges of the remaining boards bent under the weight of anyone who tried to step forward, thus rescuers had to be careful not to follow the others into the pit.

Pulling survivors out was slow work. Some bodies were recovered quickly, while others were buried under debris or caught beneath heavy beams. The work continued for hours, and people later spoke of how difficult it was simply to move around the wreckage without making things worse.

There was no question of continuing the meeting. The entire purpose of the day had been overtaken by shock and loss. Families who expected news of a legal ruling instead found themselves trying to learn whether their relatives had survived. Some noble houses discovered that their heirs were dead, and others faced sudden uncertainty about land rights and responsibilities.

For Henry VI, the collapse was more than a practical setback. Kings depended on the appearance of stability and control, and, naturally, a deadly accident at a royal assembly did nothing to help that image. He left Erfurt with the dispute unresolved and the sense that the day had exposed a weakness no one had expected.

How Writers Recorded the Event

Medieval writers approached the disaster from different angles. Some suggested that the collapse was a warning or a punishment, while others kept it closer to the facts by simply describing what had happened.

Their accounts help reconstruct the layout of the hall and the possible cause of the structural failure. None of them used modern engineering language, but their descriptions of old timber, heavy crowds, and sudden breaks paint a clear picture of the problem.

The details also reflect the world in which these men lived. Timber halls were common, practical, and usually reliable. But like any structure, they needed repairs, and those repairs were not always completed in time. When a crowd pushed an old building past its limit, the results could be catastrophic.

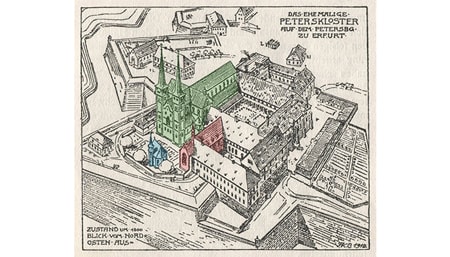

An illustration of St. Peter’s Church (green), located within the Petersberg Citadel in Erfurt (1910).

Photo Credit: Wikimedia CommonsThe Longer Impact

The collapse did not change the empire's direction, but it did reshape several families. Some estates passed unexpectedly to younger sons or distant relatives. Ties between households shifted. New arguments grew from the old ones. And for years afterwards, people recalled the day the floor gave way at Erfurt. The memory stayed alive partly because the accident was so unusual.

From a modern perspective, the disaster shows how fragile medieval authority could be. Kings and nobles often appeared powerful, yet they depended on buildings that were sometimes worn out or hastily repaired. The Erfurt Latrine Disaster highlights the gap between ceremony and reality.

The story remains one of the more unusual episodes in medieval political history. It is remembered not for military defeat or political betrayal, but for something far simpler. A floor that no one questioned finally reached its limit, and everything happened at once. The event shows how quickly plans can change, and how even the most ordinary setting can become the center of a tragedy.

Featured image: Wikimedia Commons