On November 22, 1963, John F. Kennedy was shot while riding in a presidential motorcade through Dallas, Texas. He was pronounced dead after being rushed to nearby Parkland Memorial Hospital. In the wake of his assassination, Americans demanded justice, and Lee Harvey Oswald was arrested that same day as the culprit. In an odd twist of fate, Oswald was shot on live television two days later as he was moved through Dallas Police Headquarters, taking many of his secrets to the grave.

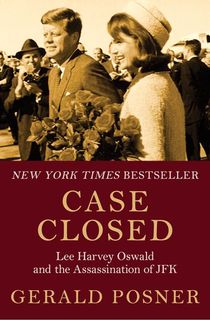

Conspiracy theories have abounded in the 60 years since JFK’s assassination, most alleging that Oswald didn’t act alone. Gerald Posner’s bold account of the events disagrees. Case Closed guides us through all the evidence that Posner has unearthed about the historic crime and Oswald’s culpability. In recent years, more information about the assassination has been made available to the American public, and Case Closed has been updated accordingly since its original 1993 publication.

Posner tells us, “The first update to Case Closed in 20 years addresses millions of pages of released assassination files as well as new witness accounts. It answers the hundreds of questions I receive regularly along the lines of ‘What is new?’ and ‘Has any new information changed your mind about who killed JFK?’”

The excerpt below addresses the public’s lack of faith in the Warren Commission’s findings, and how a lack of transparency engendered conspiracy theories. To learn more, keep reading and download Case Closed today!

Despite their differences, those books were uniformly virulent attacks on the Warren Commission, and their advocacy often diminished their effectiveness. At their best, the critics had only exposed the Commission as incompetent, but they had not established it was wrong in its conclusions.

1966 also saw the publication of Edward Jay Epstein’s Inquest, which was originally his master’s thesis at Cornell. Temperate in tone, it was a careful study of the inner workings of the Commission. Relying on fresh documents, as well as interviews with five of the commissioners and twelve members of the legal staff, Epstein charged the Commission had sought the “political truth” rather than the factual truth about the case. A “central question” that bothered Epstein was that the FBI’s report to the commissioners indicated the bullet that struck the President in the neck/shoulder only penetrated a short distance and did not exit, whereas the autopsy and the Commission concluded that it was the single bullet that went on to wound Connally. When Epstein raised the problem, it appeared valid since the autopsy photos and X rays were still locked away. It was an issue that festered until the House Select Committee’s forensics panel reviewed all the autopsy X rays and photographs and confirmed that the FBI report was simply mistaken.

Since Epstein had academic credentials, appeared to make an objective examination, and drew moderate conclusions, his book was critically accepted as an important one. Inquest prompted the mainstream press to reexamine its favorable conclusions about the Warren Report. As a result, a series of critical articles through 1966 and 1967 cast further doubt on the Commission’s credibility.

Authors like Lane and Epstein were assisted by an informal alliance of self-appointed researchers, whom writer Calvin Trillin dubbed “the buffs” in a 1967 New Yorker article. “You can compare this to a company that has a public relations program,” said David Lifton in 1967, “and a research and development program. The two puncture points at the top—what gets public notice—are Lane’s book and Epstein’s book. The ‘R&D’ program is being done by a bunch of amateurs.” David Lifton and Marjorie Field had provided Buchanan material for his book. Shirley Martin had sent copies of her taped interviews to Lane. Sylvia Meagher did the index for Inquest, and reviewed Sauvage’s book.

There was no equivalent of the conspiracy network to support the Warren Report. When the Commission disbanded, the members failed to arrange to defend their work or answer questions. Although a few books were published in support of the report, they had little impact in slowing the critical onslaught. Gerald Ford’s Portrait of the Assassin was the first pro-Commission book, published in 1965. However, it consisted largely of reprints of testimony from the Commission’s volumes and did not answer any of the early critiques. By 1967, Charles Roberts, in The Truth About the Assassination; Richard Lewis, in The Scavengers; and John Sparrow, in After the Assassination, wrote slim volumes that contributed little new information about the case; Lewis’s book was largely a hard personal attack on the critics themselves and their motivation.

Those pro-Warren Commission writers felt compelled to defend almost everything the Commission had done, and therefore weakened their own effectiveness. But they were overshadowed in 1967 by the publication of two significant books, both written by graduates of the buff network, that added to the growing mistrust of the Commission. In Six Seconds in Dallas, Josiah Thompson tried to determine what happened at Dealey Plaza by focusing on ballistics, trajectory angles, medical evidence, and eyewitness testimony. Thompson had an advantage since he was the first conspiracy writer who had studied the original Zapruder film, and his book was the first to include drawings of critical frames. His book focused exclusively on how the assassination of the President physically happened, and he did not bother with other issues. Ruby was mentioned only once and Tippit not at all. Thompson concluded there was a cross-fire in Dealey Plaza from shooters perched in the Book Depository, on the grassy knoll, and in the Records Building on Houston Street.

The second book that further damaged the Commission was Sylvia Meagher’s Accessories After the Fact. Meagher probably knew the twenty-six volumes of the Warren Commission hearings and exhibits better than any other critic. A year earlier, she had published an index to all twenty-six volumes. It was received as an important contribution for research since the volumes originally had only a name index, making it almost impossible to work effectively with the more than 1 million-plus words. Her book concentrated on any testimony or exhibits that raised doubts about the final report. Meagher was a committed leftist, and her politics are clear throughout the book. She admitted that when JFK’s death was announced, and before Oswald was arrested, she derisively told her co-workers, “Don’t worry…you’ll see, it was a Communist who did it.” When Oswald was taken into custody and she heard of his pro-Castro activities and his Russian wife, she knew he was “framed.” In Accessories, she charged that large numbers of the Dallas police were members of “right-wing extremist organizations,” and spoke derisively of the forces behind the assassination, including “American Nazi thugs.” Meagher fueled the speculation about Penn Jones’s list of mystery deaths by stating “the witnesses appear to be dying like flies.” Her invective about the Commission was as harsh as that of anyone since Lane’s Rush to Judgment.

Subsequent events, however, had significant impact on the development of the post-Warren Commission review of the assassination. On July 4, 1967, Lyndon Johnson signed into law the freedom of Information and Privacy Act (FOIA). It was revolutionary legislation that allowed private citizens to apply for the release of federal government files, even including those maintained by the FBI, CIA, and other sensitive organizations. The government agencies could only refuse to release the documents if they fell under privacy or security exemptions that were set forth in the law. Since its inception, and a subsequent amendment in 1974, over a million pages of documents have been released about the Kennedy assassination. However, the federal agencies were initially very reluctant to comply with FOIA, and researchers were often forced to resort to lawsuits to win the release of even the simplest documents.

“I think the FBI’s attitude was that they hated the Freedom of Information Act from the very beginning,” says James Lesar, whose pro bono lawsuits for documents relating to the Kennedy case, many on behalf of Harold Weisberg, have been responsible for prying more sensitive material out of the government than those of anyone else. “The FBI was originally so against the idea of FOIA that it classified early FOIA requestors as a ‘100 file,’ a domestic subversive. They also tried to make the process unpleasant. One of the little things they did at first was to provide you with atrocious copies. They would wait for the copy machine to run low or something, and provide terrible copies. But they eventually wearied of that.”

The FBI was repeatedly unmasked for lying to those who filed FOIA requests. “For instance,” Lesar recalls, “one ploy was that they said they had to search all their files page by page, because they had no index. And all the while they had a 48,000-card index in the Dallas field office. Technically, FBI headquarters [in Washington] didn’t have the index.

“In other instances, they would say there wasn’t anything in the field offices that wasn’t also kept in headquarters, that the field offices just had duplicates of what was in headquarters. That’s been proven false in several cases. The originating field office can maintain as much as four times as many documents as headquarters.”

The FBI was not alone in its dislike of FOIA. “The CIA, NSA, military intelligence,” says Lesar, “were all very close to the FBI in their distaste for FOIA. However, they have much better tools to fight FOIA requests, because they have national security and the compromise of sensitive sources as strong reasons for withholding information.”

Want to keep reading? Download Case Closed today!

This post is sponsored by Open Road Media. Thank you for supporting our partners, who make it possible for The Archive to continue publishing the history stories you love.