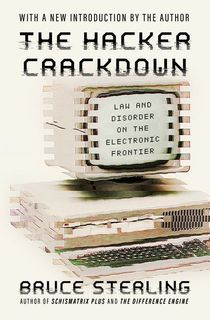

In 1992, Bruce Sterling published his first nonfiction book. A Hugo Award-winning science fiction author and a founder of the steampunk subgenre, his work includes futurist novels and short stories, such as Heavy Weather and Schismatrix Plus. Sterling earned a journalism degree from the University of Texas in 1976, but it wasn’t until The Hacker Crackdown that he turned his attention to nonfiction.

The Hacker Crackdown explores the subculture of hackers in the early days of the Internet, as well as the American government’s efforts to keep them in check. It’s been described as the “first mainstream treatment of the subject” (Kirkus Reviews).

At the time of the book’s publication, the Internet was a very different place than it is today. It wasn’t yet widely accessible to everyone around the globe, and in many ways, it represented a new frontier of exploration. No one was quite sure what to make of cyber criminals at the time, but Sterling predicted that the situation would only worsen with the advance of technology.

More recently, Sterling published a new preface to The Hacker Crackdown. Written in 2017, he discusses many of the sweeping changes he’s seen in the quarter of a century since The Hacker Crackdown was first published. Most strikingly, cyber crime has flourished since the 90s, growing from a gaggle of rebellious teenagers on message boards to a multimillion-dollar industry.

As cyber crime continues to proliferate, it carries grave implications for national security. One has only to look to the May 2021 ransomware attack on the main fuel pipeline to the U.S. East Coast to see how cyber criminals abroad can wreak havoc on millions of people. Amy Myers Jaffe, a long-time energy researcher, described it as “the most significant, successful attack on energy infrastructure we know of in the United States. We’re lucky if there are no consequences, but it’s a definite alarm bell.”

It’s an alarm bell that Sterling has been ringing for decades. In his new preface to The Hacker Crackdown, Sterling reflects on what has changed since the advent of the Internet and raises urgent questions about what the future holds.

Read the preface to The Hacker Crackdown below, then download the book for a fascinating glimpse into the early days of cyber crime.

The Hacker Crackdown After 25 Years

It’s a pleasure to write this heartfelt little preface about The Hacker Crackdown, which is now a historical document a quarter-century old.

This book was once a nonfiction cyberpunk romp about some red-hot futuristic topics. However, The Hacker Crackdown always had a lot of historical pondering in its pages. Not many books about computer-crime begin with Alexander Graham Bell.

While planning this book, I imagined I’d write a good strong concluding chapter for it. A stern judgement-of-history before history had judged much.

That plan of mine couldn’t work. The book was describing brief, obscure struggles on “electronic frontiers,” but they were just the temporary examples of large-scale, deeper conflicts. The fights that I saw were mere skirmishes, while the underlying culture-wars had deep roots in conflicting values from long-established institutions.

I could describe my various passing agitations, confiscations, show-trials and police raids, but the human condition lacks any neat summaries.

So I offered no conclusions; I just left the book open-ended. I closed my narrative with all the combative interest-groups somehow gathered in the same uneasy boat, face to face, with their cocktail glasses. They had met one another, and they were starting to grasp the vast scope of their troubles, but they hadn’t solved much of anything.

Related: The Best Netflix History Documentaries Streaming Now

When law met disorder on the electronic frontier, justice did not prevail. The Hacker Crackdown closed by suggesting that a lot more disorder was coming. That’s indeed what happened. A generation later, the consequences are obvious.

When the electronic culture of the 1990s tsunami-surfed around the globe, its disorders scaled up globally. Billions of new people arrived in cyberspace. Much wealth, fame and power ensued, and disruption abounded. Frauds became industries. Flaws became business models. Market tremors became world convulsions. Most every little bad frontier element in this book became some much bigger form of badness.

I rarely write about computer crime any more. However, I’ve maintained many contacts and sources in that milieu, so I’m aware of its passing shadows. Electronic crime is flourishing as never before. The scope, scale and brazen ambition of it are amazing. A week can scarcely go by without some dismal development that dismays and disgusts.

Cybercrime prevention has always been known for its wild-eyed alarmist hype and its vaporous claims of huge damages (and it still is). However—like many people who pay attention to police—I’ve found that the unhappiness of the noir side of life has darkened my world-view. Worse yet, in many ways, it’s truly become a darker world.

The Hacker Crackdown was a popular true-crime book. As efforts like that go, it was a success. It found a large readership. Reviewers were kind about it. Publications sought out my opinions as a social commentator on the issues on the book. Many people with a stake in the results were happy that the book existed.

When The Hacker Crackdown was freely released on the Internet, it went viral worldwide. That moral gesture I made, of simply giving away the text of a commercially published book on computer networks, brought me a lot of friends.

But an intimate understanding of crime also brings sadness. My sadness comes from my pained awareness of many sordid details about how people can misbehave to one another. My sadness came from understanding the institutional cruelty of trials and prisons, of social ostracism and deliberate acts of punishment.

I’m not such a delicate fellow that I was traumatized by knowing this. I came to understand that acts of crime and punishment are the way of the world. However, over the long term, over twenty-five years, I have to confess that the burden of that understanding weighed me down. That was the legacy of this book that has lasted for me personally.

If you choose to read books like this one because you think that transgression is romantic, that broken laws are fun and exciting, I think you should let me warn you about that a little. Actually, yes: youthful hijinks are delightful, and the past’s rules must be broken so that the future can breathe. I know that.

Related: 8 Entertaining and Informative YouTube History Channels

As the Japanese say, “Even a demon is pretty at sixteen.” But as a criminal scene gets older, and richer, and seamier, and more sophisticated in its depredations, it doesn’t stay cute.

That fact—that many cool cyber-gadgets were involved in crimes—that fact meant little. You’re probably reading this book on some piece of digital hardware that you will throw away pretty soon. The hardware comes and goes with the seasons of the technology business. But malice and cruelty, and the melancholy of punishment, they have staying-power.

Mind you, I’m lamenting about all this, although I personally did very well because of The Hacker Crackdown. By studying crime I was wading in tar, but I got all kinds of benefits. Cops were kind and respectful to me; as a creative who is a bohemian “cyberpunk,” I was never once scolded or repressed by the authorities. As a novelist, I’ve always gotten along fine with civil libertarians and free-expression advocates. Criminals worldwide wrote me fan email. Everyone was nice to me. When the book’s issues were topical and relevant and cyberculture was booming, I felt proud to have written The Hacker Crackdown.

But after twenty-five years, that hoopla has faded as such things must, and I’m much more aware of crime as a lasting and tragic aspect of the human condition. Computer crime today has achieved all the grimly persistent, socially corrosive aspects of much older forms of organized crime.

Back in the 1990s, we had loose gangs of high-IQ American teenagers lurking on bulletin board systems. In the 2010s, we have truly sinister enterprises such as the Chinese Advanced Persistent Threat, the Syrian Electronic Army, multi-million-dollar street-gangs of ATM bank robbers, encryption kidnappers who can hold hospitals for ransom, plus a multinational rainbow panoply of disinformation propagandists, fraudsters, money launderers, state-supported cyberwarriors, darknet drug dealers, and security mercenaries. The chance that these malefactors will get repressed by a justice-minded digital New World Order is next to zero.

Even in those older days, when digital crime activities were much smaller, more obscure and more eccentric, because they were human actions arising from bad intent, they had a moral taint.

To put it simply: twenty-five years have taught me that high-tech badness shares the lasting badness of other forms of human badness.

Certain forms of computer-crime are so abstract and apparently victimless that they seem almost theological. They just don’t “feel bad”—but I suspect that’s a problem with our cultural sensibility. I surmise that they truly ARE bad, but we don’t yet know how to feel that. When the novelty wears off, when our cultural understanding matures, when we get more familiar with our various digital misdeeds, we’ll come to know many things we do gleefully now as our period’s native vices.

Related: 4 Interesting Facts About Space That Will Blow Your Mind

For instance: there’s something unnerving about the unhealthy hacker habit of obsessively scraping away for any tiny flaw, any unheard-of vulnerability in code. Gloating over vulnerabilities—which are the human weaknesses of others—and searching avidly for zero-days to sell to a crime market: that highly modern activity gratifies some dark urge that is far indeed from “quality assurance.” This uniquely modern form of obsessive-compulsion is not illegal, and I’m not saying it should be. But I’m not a judge or legislator: I’m a novelist. So, I get a genuine Sartrean nausea from that form of native-digital wickedness.

Frontier people, by definition, lack civilization: frontier people are hicks. That’s who we are (or were until recently, anyhow). That fact implies that we must be rude and crude people, and, probably, our electronic vices are worse than we understand. Someday, I think, we digital folk will become embarrassed by our greed, our bad frontier manners, our lynch-mob justice, and, especially, by our relentless, thoughtless exploitation of those helpless, backward, analog indigenes.

We might have to get older and grayer to feel grown-up regrets like that, and maybe our moral judgements will have to become more rigid and fixed, like mine are nowadays. But the clock will never stop ticking, so it’s likely bound to happen somehow.

Another thing: The Hacker Crackdown is an American book. In the years that followed this book’s publication, I became a travel writer. In Russia, Eastern Europe and the Balkans, I saw a lot of digital activity by people who were entirely unrestrained by any American police force. Hackers-without-crackdowns, you might call these acquaintances.

The Hacker Crackdown belonged to a 1990s era when everyone in cyberspace was eager to spread worldwide access to the tools—when the “digital divide” was a major social issue. Those days are gone. Cyberspace now seethes with frenetic activity in huge, ancient societies far outside American borders, in cultures where custom, habit, etiquette, obligation, honor and raw fear count for a whole lot more than American dollars and a Constitution.

So, as cyberspace globalizes, and also balkanizes, it takes on everybody’s troubling aspects, not just a few distinctly American cultural quirks. Human wickedness has been global for quite a while now—since our beginning, really. It won’t get tamed by baked-in code structures minted in Silicon Valley.

That larger sensibility, with its bigger scopes of time and space, is absent from my dated little book. However, I can’t blame the book for today’s current situation, and I’m still glad that I wrote it. I feel happy for the chance to add this ambivalent addendum to it now.

Almost every person described in this book is burningly avid for better, faster, stronger computer hardware. That’s what that historic period wanted most, that was the desire closest to their hearts, and indeed, they got what they wished for. We have plenty of cybernetic gizmos now, literally billions of them. Pointing out that we still lack justice is likely the proper attitude for this historical juncture.

A final word. The events in this book are becoming steadily more obscure. Their core concern of this book is odd or corrupt activities using obscure and extinct machines. Also, as a writer, I’m a fantasist; I write science fiction by choice. So I have an intuition that people fifty years from now, or a hundred years, or more, might gaze into this book and conclude that it must be nonsense. Some invented fantasy world, a mere scramble and scrimmage of oddities, made up for amusement.

However, I can promise future readers—really, I give my word of honor—that everything in this book really happened.

Related: 8 Exciting New History Books to Dive Into

This book is old and can only get older, but it was accurate, and that virtue does not fade with the years. I must boldly assert that posterity can rely on my reportage. I was educated as a journalist in college; I graduated, that was my degree. Although I write fiction, I have always felt that the ethical framework of a journalist was a good moral structure for me. By my nature, I’m a curious wanderer, recklessly keen to pry into many odd things that are basically none of my business. The ethics of journalism, which were diligently taught to me by the professionals of an earlier generation, have helped me to do less harm.

The profession of journalism has been shattered since the days in which this book was written. Journalism, “the news of the day” as chosen as fit for print, was hammered into digital bits. The twentieth-century journalism of newspaper stands, wire-service feeds, cabled phones and tape recorders, I was neck-deep in all that when I wrote this book. That living milieu has become a mere scattering of extinct artifacts.

That’s what happened in the world I inhabited. That process was entirely fascinating. For better or worse, I’m truly glad that this colossal transformation existed within my own lifetime. It was a privilege to see it occurring. I have lived through an epic revolution, a huge change in the habits of mankind.

So I’m glad that I knew about journalism, which gave me a method to inquire, to gather evidence, to seek understanding from other people, and to bear witness to events, and to tell, at least, some of the truth. What a joy to be able to write about such strange things.

Want to keep reading? Download The Hacker Crackdown today!

This post is sponsored by Open Road Media. Thank you for supporting our partners, who make it possible for The Archive to continue publishing the history stories you love.