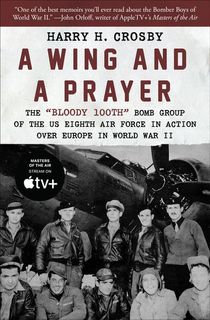

The Eighth Air Force’s 100th Bomb Group was established on January 28, 1942, soon to take to the skies and make a mark on the world with fortitude, daring acts of bravery—and rumors that it was jinxed. Moving overseas by June 1943 to operate out of the UK, the 100th took part in the Combined Bomber Offensive over Europe, where they managed to hammer blows at the Nazi war effort despite incurring heavy losses from the German Luftwaffe. Nicknamed the “Bloody 100th”, a nod to the heavy casualties it sustained, the 100th BG is the subject of Harry H. Crosby’s memoir A Wing and a Prayer.

Crosby served as the unit’s lead navigator during 37 harrowing missions, including one incident that earned him the Distinguished Flying Cross. An intimate account of his time with the Bloody 100th, his book has been called “an evocative and excellent memoir” that “re-creates for us the sense of how it was when European skies were filled with noise and danger, when the fate of millions hung in the balance” (Library Journal). Crosby himself will soon be portrayed in Masters of the Air, a miniseries developed by Tom Hanks and Steven Spielberg based on the exploits of the 100th BG, in which he will be played by Irish actor Anthony Boyle.

In a recent letter shared by Crosby’s children, they wrote, “Our father was proud of his service (his medals include the Distinguished Flying Cross, Bronze Star and Croix de Guerre). But he would be most deeply proud that his book, through the Masters of the Air series, will contribute to the lasting story of the European air war in World War II and the incredibly courageous young Americans who fought it.”

Masters of the Air premieres on January 26 on Apple TV+. In the meantime, you can read the passage below to get a sneak peek at A Wing and a Prayer, then download the book today for a gripping true WWII account of intrepid aircrew.

Because of General Eisenhower’s edict that all troops should be fully informed about what was going on, the 100th current events room was a masterpiece. Two officers from S-2, our Intelligence section, and two enlisted men devoted almost full time to keeping it up.

There was news from home. Both political parties were getting ready for the next election. Against President Roosevelt, the Republicans planned to run two governors, New York’s Tom Dewey and California’s Earl Warren. They were trying to get the candidate of four years before, Wendell Willkie, to cooperate. Baseball’s New York Giants and the Brooklyn Dodgers played a special game to raise money in the fifth war bond drive.

Every week we got a batch of newspapers from different parts of the country. They were usually about ten days old, but they gave us a chance to see what was going on in our own parts of the country. From the Des Moines Register and Tribune I learned that the University of Iowa had become a Navy pre-flight training school and the cadets were having a ball dating lowa coeds. My former girlfriends. I envied them. They were a million miles away.

From flimsies made from messages that came in over the code wires in our cryptography section, we got up-to-date reports on the positions of our troops in all theaters. On one wall map a ribbon stretched along a series of pins represented the slowly progressing front in France. On two other wall maps, we could see the CBI, China-Burma-India, and the Pacific theaters.

In the New York Times I read that Omar Bradley and his American troops had captured Cherbourg and 30,000 prisoners. In just three weeks after their original landing in Normandy, Allied land forces had “liberated more than 1,000 square miles of France, captured more than 50,000 prisoners, and had destroyed four German divisions.”

That was why we pounded the French coast so much.

Apparently our attempts to be deceptive, all those bomb runs on different parts of the coasts of Holland and France, were to some degree effective. I read that a British naval intelligence officer said that the Germans had been so skillfully outmaneuvered that they massed their defenses at Calais and Boulogne, leaving Normandy without protection.

Axis Sally had been wrong. We fooled the Germans.

Thanks to the reading room, for the first time I began to appreciate the Fifteenth Air Force, which was operating out of Italy. On a day we in the Eighth were stood down because of clouds piled 25,000 feet over England, “the 15th went out in full force and bombed Vienna. About 700 war planes were in the air.” The Fifteenth was getting as big as the Eighth.

Fascinated in the reading room by the moving lines of pins and red string, we watched the Fifth Army fight its way up the Italian boot. Way out in the Pacific, in Saipan, our boys were fighting for every inch. Marines had “scaled Mount Tapotchau and dug in at the summit.” Navy planes were bombing Guam. Allied forces had captured Mogung in Burma and gained on all fronts from the Indian border to China. The Japanese were attacked in Hunan Province.

For the global war out there, we were spectators. In England, part of our war was the same. A few months before, we could see our targets, the cities, the planes on the runways, the antiaircraft blinking up at us. Now, with blind bombing, not only did we not see the cities, we didn’t see the bombs explode. They just disappeared into the clouds.

We had two missions, strategic and tactical. The first, bombing Germany, knocking out factories and communication, through the clouds, was called Operation Clarion. It was unreal. During the tactical part, when we were a tiny segment of Operation Overlord, we flew in low to destroy bridges, railroads, and airports. On those missions, we could often see the troops we were supporting.

On June 17, we went through a briefing, got ready to bomb a French airfield at Melun, and waited at the takeoff strip.

Mission scrubbed. Weather.

On the eighteenth, we were briefed to bomb an oil refinery in Ostermoor, Germany. Since the 100th was to lead the whole task force, I would fly. The lead pilot was Frank Valesh, with Al Franklin as navigator and Jack Johnson the Mickey operator. This crew had once been called “the worst fuck-ups in the Eighth,” but now they were one of the most disciplined and highly skilled. I looked forward to flying with them.

The crew was so good that for almost the whole mission all I did was just sit there. No way for me to screw up.

I went into action just once. After the navigator got the wing together he headed for the division rendezvous, climbing on the way. As we climbed, the tail wind increased and Al and I could see we would be six minutes early.

“Radius of action to the right, Croz?” Al asked.

I nodded.

We were supposed to fly about three minutes off 45 degrees to the right—which was upwind—and then make a 90-degree to the left for about two and a half minutes—downwind—and back on course with a 45 to the right.

As we went out to the right I sensed that something was wrong. I couldn’t see anything but clouds but I had the radio compass tuned to Splasher Six and the pointer was changing too slowly.

I went on intercom.

“Command navigator to pilot, you better rack it around ninety degrees to port.”

Valesh was not happy about my interference.

“Al, what’s going on?”

“Goddamned if I know. But you better do what he says. He’s been here more times than we have.”

The command pilot came on.

“Croz, you better be right.”

I didn’t feel very sure, and I began to sweat.

When it felt right—and I didn’t have any better evidence than that, I came back on the phone.

“Now 45 to starboard, on original heading.”

I quickly flipped our radio to the buncher at Great Yarmouth where we were to meet the other wings. Thirty seconds for the ETA.

Not at twenty-eight seconds, nor at thirty-two seconds, but at thirty seconds, the needle went around. The pilots saw it. Back in the radio compartment the Mickey operator saw us cross over Great Yarmouth on his radar. He came on intercom.

“Goddamn, Captain Crosby, how did you do that?”

How? I had no idea. Aerial navigation was no exact science, and I always felt I was less exact than anyone else. Skills? Experience? Luck? I had no idea. Was this the navigator who, just a year ago, missed England by a hundred and fifty miles?

The mission with Valesh when we saw almost no opposition made me realize dramatically that the Eighth was doing its part in winning the war. We had knocked the Luftwaffe out of the sky.

That we were winning the war was demonstrated by another development. On all bulletin boards a notice appeared: “From this day forward, officers will no longer be required to wear side arms.” Nothing more, but we knew what it meant. We no longer expected the Germans to launch an invasion of England. I was glad to get rid of the heavy, dangerous .45 revolver. From then on, I carried it only on missions.

I always felt strange about carrying a gun. Most of the time I could help to destroy a whole city and sleep that night. But I never liked carrying that revolver. I might get shot down and have to shoot someone.

As June was becoming July, it was deep and shallow, shallow and deep. Germany and France, France and Germany. If the weather was bad, we went in deep. If it was clear, we went to France.

On the long runs, our crews took off, hit the soup at 200 feet and broke out at 22,000. With no sight of land, but with the guidance of the Mickey operator, they coasted along over those billowing pillows for three hours. The command pilot called for the pilots to tighten up. The formation made a hard left turn, dropped its bombs onto something, and came home.

On the whole mission, the only evidence of the enemy was the flak over the target. There were black bursts of flak as the groups made the hard left turn at the I.P.

In the pictures which the photo officer brought home, those explosions out there, as the planes floated along, looked like black blossoms in a white, billowy, and lovely world.

To keep reading, download A Wing and a Prayer today!

Sources: The National WWII Museum

Feature image of Harry L. Crosby via American Air Museum in Britain

This post is sponsored by Open Road Media. Thank you for supporting our partners, who make it possible for The Archive to continue publishing the history stories you love.